There had also been a great number of roof tiles blown off, so Alison was piling them up in the front yard when I arrived. I started to pitch in, but the bulk of the work had already been done.

The scene between Sergeant Elliot and Mac was still lingering in my mind. “Imagine,” I said after a while. “Mac thought he was honoring Sergeant Elliot, and instead he was holding him back. You just never know the effect you’re having on other people.”

“I do,” Maxine said.

“Really,” Alison responded.

Paul and Maxine were not helping stack the tiles—passersby would see tiles stacking themselves, and Alison was already known in parts of town as the “ghost lady”—but they were watching Melissa, Alison and me stack them.

Alison looked at me and sighed. “These are a lot of shingles,” she said, pointing to the intimidating pile. “I’m going to have to go up on the roof and replace them.”

The Victorian is a very tall house, and reflexively I looked up. “That seems dangerous,” I said.

“Gotta get done.”

“You could ask Tony,” I said of her contractor friend.

“Tony’s doing repairs on his own house, and then has about seventeen jobs lined up. That’s why I had to ask Murray for the chain saw; Tony’s just too backed up to come. Who knows how long it’ll take to rebuild everything? My roof is the least of anybody’s problems around here. Once the stores are all restocked, I’m going to get some shingles and get up there.” She didn’t look happy about it, and I didn’t blame her.

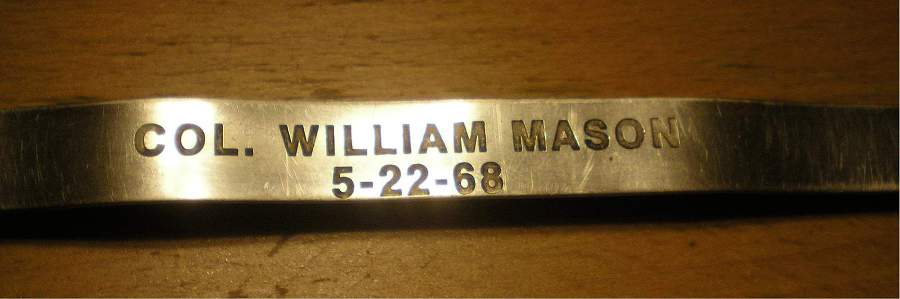

“Grandma, you’re not wearing your POW bracelet,” Melissa said. “Did you just leave it home today?”

“No. I’ve decided not to wear it anymore. I don’t want to strand Colonel Mason the way the sergeant was stranded.”

“Well, you have the advantage of being able to see Colonel Mason if he comes to ask,” Alison pointed out.

“Yes, but suppose he can’t.” I replied. “Suppose he never made it home from Vietnam, and he’s stuck there. I don’t want to take that chance. I think the best way to honor him is to allow him peace.”

“You’re very conscientious,” Alison said.

“What’s ‘conscientious’?” Melissa asked.

“Like Grandma.” Alison glanced up at the roof again and looked worried.

I thought about that when I went home that night. Alison told me a few days later that she’d bought the shingles and was planning on climbing up to the roof the next day to begin installing them.

But when she woke up the next day, the roof had been completely repaired.

Epilogue

“It was you, wasn’t it?” I asked Jack now, on our way to Alison’s house for dinner with the girls, the ghosts and Josh Kaplan.

“Of course it was me; you knew it was me,” he said, “sitting” in the passenger seat. I’d had to talk Jack out of putting on his seatbelt, pointing out that there was little harm that could befall him these days. “I wasn’t going to let her climb up there and break her neck.”

“You’re a good dad.”

“Better now than then,” he said.

“Don’t sell yourself short,” I told my deceased husband. “Your heart was in the right place.”

“Technically, my heart is in an urn somewhere, isn’t it?”

I didn’t answer that.

• • •

“You’re still wearing that?” Marilyn Beechman asked. She pointed to the POW bracelet on my left wrist. It was some the worse for wear after four years, but not rusted or dirty. I glanced at it.

We were at her apartment in Matawan, where she’d just moved to be with her boyfriend (later husband, later ex-husband), Roy, and Marilyn was cooking dinner just to prove to me that she could. Chicken Parm. She was sautéing the chicken in preparation for the oven as we spoke.

“You told me I had to wear it until Colonel Mason was found or declared dead,” I said. “I haven’t seen anything that said he was either.”

Since I’d gotten to the apartment and Roy had taken my coat—and then disappeared into the bedroom, saying he wanted to let us have our “girl talk,” a sure sign that he’d eventually be Marilyn’s ex-husband—there had been an incessant banging coming from somewhere in the place, but Marilyn was not acknowledging it.

“They’ve found pretty much everybody,” she answered. “There’s no reason to think he wasn’t among them.”

“I wrote away to the Department of Defense and never got an answer,” I said. The pounding wouldn’t stop. “What is that noise, anyway?”

“Oh, sorry,” Marilyn told me. “The super sent up some guy to fix the ceiling in the bathroom, and he’s been hammering all day. It’s making me crazy, but he’ll leave soon. They shut down at six. You really wrote to the Department of Defense?” Marilyn repeated with a chuckle. “You’re so naïve. They’re never going to tell you the truth. Hasn’t this Watergate thing taught you anything about trusting the government?”

“Well, maybe I should take the bracelet off for good, then,” I said.

“Don’t do that,” said a voice from behind me.

Holding a step stool, a young man in painter’s overalls and a canvas cap was walking out of the bathroom. He looked at Marilyn. “Ceiling’s just about fixed,” he said. “I’ll come back tomorrow to compound and sand it, okay?”

“Sure,” she said, stirring jar marinara sauce in a pot and not looking up.

“Why shouldn’t I take it off?” I asked the super’s assistant. He had a small frame but solid muscles, sort of like John Garfield.

“Because it’s a way of letting the guys who fought know that you understand what they went through, and you want all their buddies to get home safe, even the ones who are still being held prisoner.”

“Vietnam was a mistake,” Marilyn said.

The young man shrugged. “Governments make mistakes. Should we punish the poor guys who had to carry them out? Some friends of mine were there. Some didn’t come back. I don’t care about the politics. I care about my friends. I say you should keep wearing the bracelet, ma’am.”

“Ma’am?” I said.

“Miss?” he asked and smiled.

I decided right then I would keep wearing the bracelet for a while.

And I married the young handyman the following year.

Addendum

Lieutenant Colonel William Henderson Mason was born October 12, 1924, and was lost in Laos on May 22, 1968. His crew included Captain Thomas B. Mitchell, Captain William T. McPhail, Seaman Apprentice Gary Pate, Staff Sergeant Calvin C. Glover, Aircraft Mechanics Melvin D. Rash and John Q. Adam.

The crew departed Ubon carrying passenger Major Jerry L. Chambers. Radio contact was lost and the aircraft did not return to base. There was no further contact. Because Laos did not participate in the Paris Peace Accords, no American held in Laos has ever been released.

Colonel Mason was a 1946 graduate of West Point and was promoted to full colonel while classified as missing.

A group remains burial for the crew, including Colonel Mason, was held on June 10, 2010.

Source: POW Network, 2010, www.pownetwork.org/bios/m/m019.

Photo by E. J. Copperman, taken on the kitchen table, May 2013.