Villages might be exclusively Kurdish, Armenian, or Greek, although sometimes two groups would share a town—Turkish and Armenian, Turkish and Greek. All were “Ottomans,” but each group traced a lineage back to a distant and sometimes mythic past. Larger towns were multiethnic, with quarters dedicated to particular groups. In the largest cities, neighborhoods could support a mix of peoples: Turkish and Armenian peasants, Armenian merchants and artisans, as well as Arabs, Jews, Kurds, Tartars, even Roma.

In many rural areas, whoever owned the land owned those who worked it, and when the land was sold, the peasants living on the land came with the property. This system of serfdom was supported by the millet law. Most Christian Armenian peasants had no economic power and no rights. In the east, these vulnerable peasants were surrounded by Muslim tribes, particularly Kurds, whose religion conferred superior social status. Many Kurds were pastoral nomads, not settled in farms and towns as were most Armenians. Over the summer months, Kurds would pasture their animals in the highlands, while the sedentary Armenians tended their crops. But come winter, when the freezing cold and deep snow forced both Kurds and Armenians indoors, it became convention that an Armenian must house any Kurd who demanded it. Not only were the tribesmen allowed to take up residence in Christian homes (along with their animals), but also as Muslims, they were allowed to enjoy all the perks that the head of the household enjoyed, which included, in some cases, the peasant’s wife.

When Abdul Hamid II became sultan in 1876, he found himself caught between two conflicting trends. The empire was buckling under the burden of high-interest loans and many felt that the economy had to be modernized. The financial crisis was tearing the empire apart. Outlying territories, inspired by Greek independence in 1829, had been attempting to break away from the empire for decades. At the same time, entrenched power blocs preferred the status quo.

In the years before Abdul Hamid came to power, Ottoman lawmakers, desiring to see the Ottoman Empire become a constitutional monarchy, had pushed through a progressive series of edicts known as the Tanzimat. These efforts led to the establishment of a constitution in 1876 (only months before Abdul Hamid took power) in the hope of bringing the Ottoman Empire in line with the norms of the “Concert of Europe.” When Abdul Hamid first became sultan, the empire was struggling to adjust to this new systems of governance. In the same year, 1876, with yet another war with Russia looming and the domestic economy falling apart, Abdul Hamid suspended the new constitution and disbanded parliament, bringing the era of reform to an abrupt end. In contrast to the idealistic “Young Ottomans,” moderate precursors to the Young Turks who lobbied for equality amongst all the sultan’s subjects, and their European friends, Abdul Hamid saw the constitution, and the system of governance it represented, as untenable. The sultan, a fastidious and bureaucratically oriented man, was afraid of losing his grip on all the outlying regions of the empire. His response was to tug harder on the reins.

In the eastern frontier lands, the uncontrollable power of the Kurdish chieftains diminished the power of the government in the east. The sultan tried to solve the Kurdish problem in two ways: first, by breaking up the most belligerent tribes (either by moving them or arresting or killing their leaders), and second, by co-opting the tribes, incorporating them into a paramilitary called the Hamidiye (named in honor of Abdul Hamid). These Kurdish units were dedicated to the sultan and replicated what the Cossacks had done for the tsar: provide a ferocious advance guard terrorizing problem areas.4 Because the Turkish army en masse was more powerful than these Kurdish units, the Hamidiye could be disciplined if necessary. If they went rogue, the leader could be captured and either imprisoned or executed.

This, in turn, heightened the danger for Armenians living in the eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire, the areas closest to Russia and Persia. For hundreds of years, the balance of power between the Kurds and the Armenians had been stable, if tense and often violent. But by the middle of the nineteenth century, the fragmented Kurdish tribes became even more lawless. It was impossible for the sultan’s troops to be everywhere at once. Besides, restricting what the Kurds did to the Armenians was not a priority for the Sublime Porte.

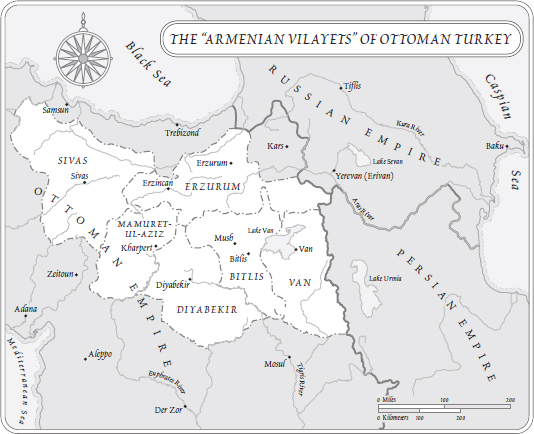

This bad situation came to a head in 1894, 1895, and 1896, when Sultan Abdul Hamid let the Hamidiye loose on the Armenian villages in a series of bloodbaths, crushing any sign of insurrection, real or fabricated. The violence was terroristic, leading to hundreds of thousands of civilian fatalities. News reports, as well as dozens of books published at the time, describe immolations, flaying, rape, dismemberment, and massacre. Overwhelmingly, the vilayets in the east bore the brunt of the killings. The goal was to undermine Armenian support of the Russians in their perennial war with the Ottomans. This began what Vahakn Dadrian has called “a culture of massacre” in Asia Minor that persisted from that period through World War I.5

Though Armenians lived throughout the Ottoman Empire, these six vilayets featured major Armenian populations and endured major massacres under Sultan Abdul Hamid’s rule.

With no recourse against government-sponsored violence, in the late nineteenth century, Armenians formed revolutionary societies, notably the Armenakan Party, the Hnchag (Bell) Party (or Hnchags), and the Hai Heghapokhakanneri Tashnagtsutiun (the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, or ARF, also known as the Tashnags). Emboldened by revolutionary activity in Russia, these organizations had committed themselves to education of the peasantry, agricultural reform, and the establishment of a constitutional and/or socialist government. They were also, by their own admission, terrorist.6

In the end, despite the idealistic goals they outlined in their manifestos, violence as a means to an end would come to define both the Hnchags and the Tashnags. Both revolutionary organizations began their “work” by assassinating small-time Armenian and Turkish officials they viewed as traitors. Bloodied corpses would be dumped in the streets, a note pinned to the jacket lapel describing the offense. Suspected spies were assassinated. In an operation called “The Storm” (P’ot’orik in Armenian) in 1900, family members of wealthy Armenians were kidnapped in order to extort funds to support revolutionary activity,7 a tactic still practiced in the Middle East in the early twenty-first century.

Because non-Muslims were forbidden to carry arms in the Ottoman Empire, Hnchags and Tashnags secretly distributed firearms to villagers for self-defense against the violent Kurdish tribes. In addition, the Armenian revolutionaries sometimes attacked local Turkish officials with the deliberate intention of inciting retribution by the Turkish army. The hope was that the resulting massacres of the innocent local populations would gain the attention of Europe. They did exactly that as Western newspapers trumpeted the news of atrocities. The Armenian revolutionary organizations, particularly the Tashnagtsutiun, or ARF (parent organization to Nemesis), were a real force in the Ottoman Empire.

These Armenian revolutionary groups not only were inspired by the Bolsheviks in Russia (Stalin, one of the early leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution, had been a divinity student in Tiflis) but also looked to the French Revolution and other similar movements that celebrated progress, enlightenment, socialism, nationalism, and social Darwinism. With their headquarters located safely beyond the reach of the sultan and his spies, the Armenian revolutionary groups sent operatives across the borders and back into the empire. Armed teams of fedayeen operated throughout eastern Turkey and the Caucasus. The volunteer fighters adopted an Persian-Arabic name (fida’i, or “devotee”), which they took to mean “he who is committed” or “he who is sacrificed.” “Field workers for the parties were known as ‘apostles’; guerrilla fighters, who had given up comfort to sacrifice their lives for the people, became ‘martyrs for the cause’; priests blessed the soldiers on the eve of major battles.”8 Attacks against the Ottoman government were called surp kordz, or “holy task.”