“This man, by his carelessness in his duties as clerk, caused us to lose a rucksack containing notebooks filled with irreplaceable data,” Rosa Harsch said. “Ten strokes.” And the process was repeated exactly as before.

When it was over, the members of the party dispersed to their various sleeping quarters and the woman returned to Illya by the fire. The flickering light smoothed out the network of fine wrinkles around her eyes and softened the contours of her face. From a certain rigidity about the waist and the twin bulges of flesh at each side of her back just below the arms, he guessed that she was wearing a laced corset beneath the shirt. But for all that she was still remarkably attractive.

“I see you have no color bar in your expedition,” he said lightly as she unbuckled the Sam Browne and dropped to the ground beside him.

“No,” she said seriously. “No color bar. Everyone is treated the same. It is best. In places as remote and as dangerous as this, it is unfortunately necessary to impose strict discipline. Without it, they take advantage—all of them. And that impairs efficiency. Without complete efficiency, an expedition of this sort is doomed from the start.”

“They all seem to take it for granted. Nobody resents such…discipline…being administered by a woman?”

“But of course not. I am the leader of the expedition.”

She offered Kuryakin a cigarette, and lit one herself. “And now,” she said, leaning towards him in the glow of the embers, “it is time to relax. Tell me about yourself; you could interest me, young man…”

Chapter 11

School is Dismissed.

WHILE ILLYA HAD been filling his radiator from the trickle of water in the wadi, Napoleon Solo, more than a hundred and fifty miles to the northeast, was guiding his horse between the stones of a moraine sloping down to a plain. Somewhere ahead of him, the caravan with the camel carrying the container of Uranium 235 was winding its way among the tall grasses and scrub oak that had supplanted the ubiquitous thorn trees.

He rode slowly, the homing device open on the saddle in front of him. At first, turning the pointer to ensure that he was taking the direction in which the bleeps were loudest was almost a formality: the trail was well marked and there was no other route the caravan could have taken. Later in the afternoon, when he was climbing another of the interminable series of limestone ridges with which the country was barred, he had cause to be glad of his foresight—for the track itself petered out among a wilderness of rock outcrops, and he was constantly having to check and recheck his route. Such food as he had had been abandoned with the camel and he was ravenously hungry. He was worried about the horse, too, for the animal had taken neither food nor water since he had escaped from Ahmed and the soldiers. He had ripped a length of cloth from his burnoose to improvise a headdress against the scorching rays of the sun. The remainder of his robes he had discarded and buried with the “pilgrim’s” papers. Now—thankful that he had been wearing his bush shirt and shorts underneath them—he was again beardless and normal of nose, in the guise of Napoleon Solo: mineralogist of Russian extraction, equipped with a laissez-passer countersigned by His Excellency Hassan Hamid…

Several times he attempted to contact Illya but the radio remained obstinately silent.

From the top of the ridge, he swept the country beyond with his glasses. It was becoming less barren, definitely: there were squares of cultivation here and there, and vegetation covered the rolling contours more thickly. Far off towards a range of tree-covered hills which reared, blue-hazed, against the horizon, a long line of dust marked the position of the caravan. He slid the binoculars back into their case and rode on down.

Twice he had to skirt villages—no longer the mudwalled Arab variety, but circles of huts in the African manner—but he saw nobody. Once, though, he thought he heard the sound of distant rifle fire.

He was within a mile of the wooded hills when he saw a column of smoke rising above the trees off to the right. A moment later, hooves thundered on hard ground and he trotted the horse out of sight behind a maize hedge just before a squadron of Arab cavalry thundered past in a cloud of dust. There were about thirty of them, shouting and laughing and waving their rifles above their heads as they rode. Two of them carried the bound figures of African women across their saddles; a third dragged behind his horse on a length of rope the lacerated body of a man.

Solo waited in his place of concealment until the dust had settled. He switched on the homer again: the pips were still sounding loud and clear. He could afford the time to investigate.

Walking the horse warily between the trees, he advanced towards the column of smoke.

When he was about two hundred yards away, he found a patch of grass where the horse could graze. Tethering the animal to a sapling, he drew the Mauser and went forward on foot.

The village was completely concealed in a shallow depression. As he trod down the slope, Solo’s nostrils were assailed by the bitter stench of burning and death. Most of the inhabitants must have fled, but there were a dozen bodies sprawled in the dusty space enclosed by the ring of gutted huts.

The flames had died down, but half a dozen of the burned huts still spiraled smoke into the air. The only thing standing was the stone-built end wall of a building rather larger than the others.

Solo walked around the corner of the wall—and stopped in astonishment. The rest of the building had been made of wood, and all that remained of it was a tangle of charred embers from which wisps of smoke still rose. But it had obviously been some kind of school. Hardwood desks with iron frames had escaped the conflagration and still stood upright among the debris—and what was oddest of all was the size of the desks: with their attached seats, they were big enough for full-grown adults!

The agent turned to look at the end wall. A scorched teacher’s desk had fallen forward among the blackened timbers of a dais. Behind it, a blackboard was still attached to the plaster. Glancing idly at the chalked figures, he drew in his breath with a gasp of surprise. The top line read: Réaction de châine: fission de l’Uranium. And beneath this was the diagram:

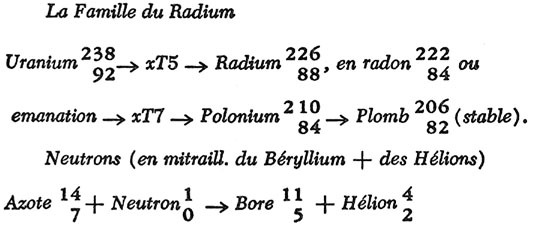

At the foot of the board was written:

W (energie de la transmutation) = mc2

(c = vit. de la lumière d’apres l’equivalence de la masse et de l’energie)

L’Uranium…

“My God!” Solo exclaimed aloud. “Atomic physics being taught here. They must be running a school for future warmongers…It seems I’m getting warm after all.”

Hurrying back to the horse, he saw a scrap of white paper lying under the trees. It was a sheet from a loose-leaf notebook. On it was written:

“Well, at least some of the class seems to have got away,” Solo muttered as he remounted and rode on along the trail.

It looked as though, wherever Thrush was conveying the Uranium 235, they must be organizing courses of instruction in its use among the dissident Africans.

Whether the sack of the village by the Arabs had anything to do with this, or whether it was merely a coincidence, he had at present no means of knowing. In any case, it seemed reasonable that the destination of the lead canister might be near at hand.

A few miles further on among the wooded hills, he reined in the horse on a crest and took out his glasses. Three ridges away he could clearly spot the caravan traversing an open space among the trees. The powerful Zeiss lenses showed him the striped blanket still in position on the camel he was following.