Early on the morning of 25 April 1915, the Anzacs stormed ashore beneath sheer cliffs on the western, Aegean side of the peninsula. I am not one of those who regard all the generals of the First World War as knaves and fools. But the senior officers who presided over the Gallipoli campaign were among the most insensitive blunderers ever to lead an army in battle. From 25 April onwards, the scene was set for the ghastly months of slaughter that followed. The Turks fought with heroic determination. Liman von Sanders and Kemal showed themselves masterly commanders. British and Anzac troops ashore suffered every kind of privation as well as danger. Occupying trenches under almost continual bombardment, they were hurled again and again into attacks that gained only a few yards of barren soil, at hideous cost.

On 15 May, Lord Fisher resigned in the last of a long series of tempestuous and increasingly demented outbursts against Churchill. When the First Lord tried to conciliate him, Fisher responded with a note in impassioned capital letters liberally interspersed with exclamation marks: ‘YOU ARE BENT ON FORCING THE DARDANELLES AND NOTHING WILL TURN YOU FROM IT — NOTHING. I know you so well! You will remain and I SHALL GO.’ The combination of the setbacks at the Dardanelles, bloody stalemate in France and Fisher’s resignation obliged the tottering Liberal government to resort to a coalition with the Conservatives.

I am among those who believe that the notion the forcing of the Dardanelles could alter the course of the war was always an illusion. First, even if the Black Sea route to Russia had been opened, Britain and France lacked sufficient weapons and shells for their own armies — they had none to spare to ship to the Russians. Second, it is highly doubtful that, even if the Royal Navy had shelled Constantinople, sea power alone could have forced the Turks to capitulate. Hamilton’s army was too small to win a land campaign unless the Turks had crumbled in its path, as they never showed any likelihood of doing. Third, even knocking Turkey out of the war would do little to bring closer defeat of Germany and Austria-Hungary. In the First World War as in the Second, victory could be gained only by defeating Germany on the Western Front, and Churchill was very foolish to suppose otherwise. Of course, a victory at the Dardanelles would have been very handy, and bolstered Allied morale. But it never looked like a war-winning stroke, and through the summer and autumn of 1915, it became an appalling drain on Allied manpower and resources.

The influential British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett travelled to London to tell every politician who would listen that the campaign was a disaster that was going nowhere. At first nobody listened, and disastrous operations continued to be carried out by disastrous generals. At the end of July, Aylmer Hunter-Weston, the butcher commanding the 29th Division who shrugged cheerfully before the landings that ‘heavy losses by bullets, mines, shells and drowning could be expected’, suffered a nervous breakdown. The August fighting cost the Allies twenty-five thousand casualties in four days. Another general wrote gloomily of one of his own formations, the 53rd Division, that it was so demoralised ‘it might bolt at any minute’. The Australian war correspondent Keith Murdoch followed Ashmead-Bartlett in reporting home that the Gallipoli campaign was futile. Loathing and contempt for British generals had become an absolute among Anzac troops.

In October, Hamilton was belatedly sacked and replaced by Sir Charles Monro, who immediately recommended that the campaign should be abandoned, the troops evacuated. Kitchener came out from London to see for himself, and endorsed Monro’s conclusion. Matters were made worse by three days of violent storms in November, which made it impossible to land supplies and worsened the privations of the eighty thousand men ashore. Some froze to death in their positions.

But the eventual withdrawal proved to be the only efficient part of the campaign. To prevent the Turks from seeing what was happening and exploiting weakness, the men in the line were progressively thinned out. On 18 December the main evacuations began, and on 8 January 1916 the last men were taken off Cape Helles. Five hundred wretched mules, the last of thousands landed to serve as pack animals, were shot on the beaches.

An Australian officer left behind a note for the Turks, asking them to preserve Anzac graves, saying he felt sure they would do this, as they had behaved ‘most honourably’ during the fighting. Another soldier messaged: ‘You didn’t push us off, Jacko, we just left.’ An Australian light horseman laid a table for four and set it with jam, bully beef, biscuits and cheese. His note said: ‘There are no booby traps in this dugout.’

The Dardanelles campaign had cost the Turks 251,309 casualties, including 87,000 dead; the French lost 10,000 killed, the Anzacs 8,709, the British 21,000. Proportionate losses were highest among the New Zealanders, in both world wars perhaps the finest of all Allied fighting soldiers. Of 8,556 who served at Gallipoli, 2,701 died, 4,752 were wounded. Compared with the slaughter on the Western Front, this toll was relatively small. The British would lose as many dead in a mere day or two on the Somme in 1916. But somehow the Dardanelles, that parade of futility played out so close to Troy, in a land and seascape steeped in classical legend, achieved a special place in the history of the war. For Australians, in the words of one of their historians, it became ‘a Homeric tale’. Ever since, they claimed it as their own in a fiercely and characteristically nationalistic fashion. Even in the twenty-first century, each year Gallipoli draws their descendants in astonishing numbers to attend commemorations. Australian folklore brands the peninsula as the place where the generals of the old ‘mother country’ grossly betrayed the young men of the dominions. This is not entirely a false image, but it is sometimes irksome to find modern Australians quite ignorant of the fact that more than twice as many British soldiers perished there as Australians.

Winston Churchill believed to his dying day that had the admirals and generals been bolder and more competent, the course of the war might have been transformed here. Few modern historians agree. The Gallipoli campaign was fundamentally flawed, as well as ineptly executed. The First Lord bore most of the bitter political recriminations for the failure. He was obliged to resign his office and accept command of a battalion in France. It was 1917 before he was again admitted to Lloyd George’s government, and some British politicians did not forgive him or forget his responsibility for the Dardanelles campaign until 1940.

Many battles in many wars seem futile to posterity, because all wars involve wasted human lives. The diaries and letters of the young men who fought and died at sea in the Dardanelles and ashore at Gallipoli are among the most profoundly moving documents of the war. To visit the battlefield is to make a pilgrimage to one of the most emotive landmarks of one of the most terrible conflicts of history, of which Alan Moorehead remains perhaps the most vivid chronicler.

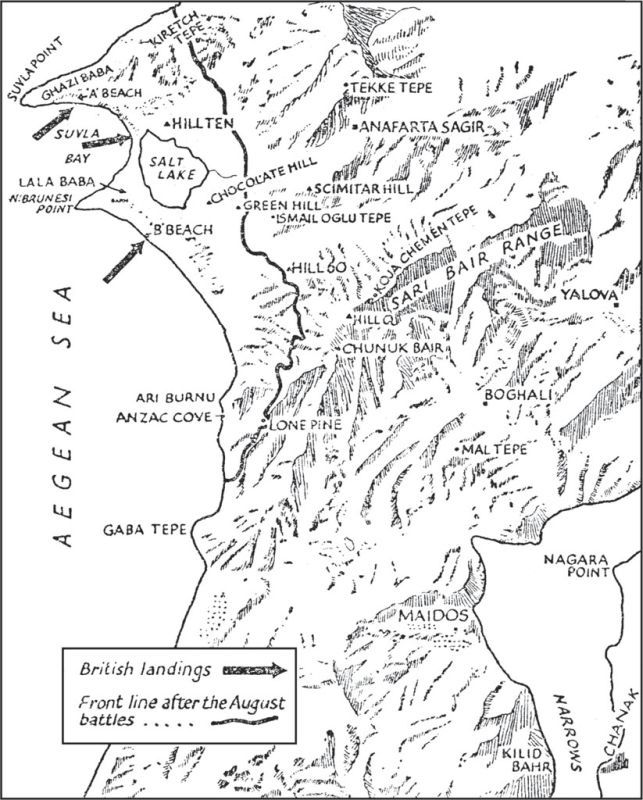

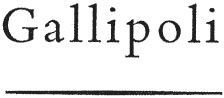

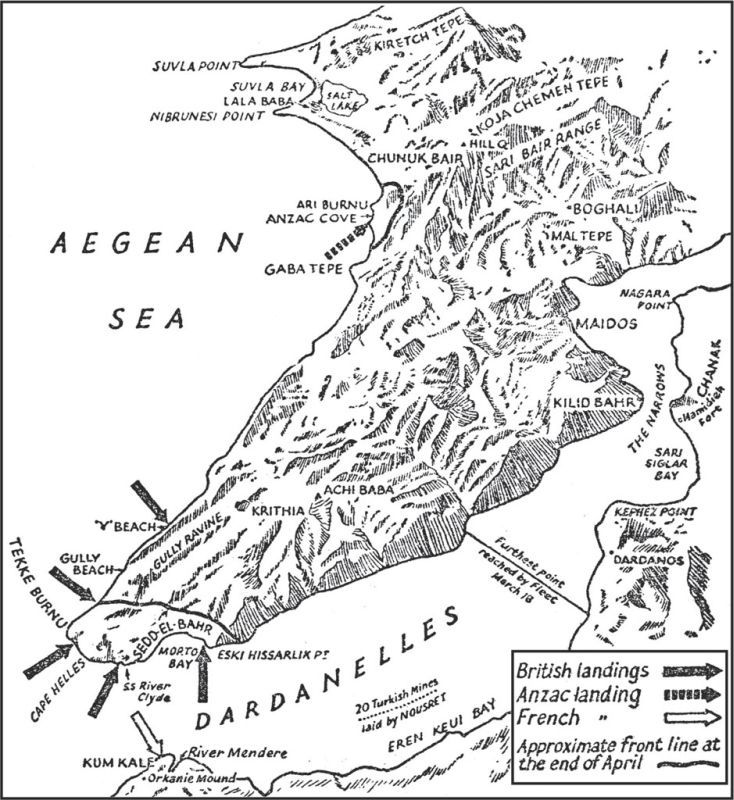

Maps

The Dardanelles and Gallipoli, 1975

Gallipoli: The Landings, April 25th