SALISBURY

Nay, ’tis in a manner done already,

For many carriages he hath dispatched

To the sea-side, and put his cause and quarrel

To the disposing of the Cardinal,

With whom yourself, myself, and other lords,

If you think meet, this afternoon will post

To consummate this business happily.

BASTARD

Let it be so.—And you, my noble prince,

With other princes that may best be spared,

Shall wait upon your father’s funeral.

PRINCE HENRY

At Worcester must his body be interred,

For so he willed it.

BASTARD Thither shall it then, 100

And happily may your sweet self put on

The lineal state and glory of the land,

To whom with all submission, on my knee,

I do bequeath my faithful services

And true subjection everlastingly. 105

He kneels

SALISBURY

And the like tender of our love we make,

To rest without a spot for evermore.

Salisbury, Pembroke and Bigot kneel

PRINCE HENRY

I have a kind of soul that would give thanks,

And knows not how to do it but with tears.

He weeps

BASTARD ⌈rising⌉

O, let us pay the time but needful woe,

Since it hath been beforehand with our griefs.

This England never did, nor never shall,

Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror

But when it first did help to wound itself.

Now these her princes are come home again,

Come the three corners of the world in arms

And we shall shock them. Naught shall make us rue

If England to itself do rest but true.

⌈Flourish.⌉ Exeunt ⌈with the body⌉

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE

ENTRY of ‘a book of The Merchant of Venice or otherwise called The Jew of Venice’ in the Stationers’ Register on 22July 1598 probably represents an attempt by Shakespeare’s company to prevent the unauthorized printing of a popular play: it eventually appeared in print as ‘The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice’ in 1600, when it was said to have ‘been divers times acted by the Lord Chamberlain his servants’; probably Shakespeare wrote it in 1596 or 1597. The alternative title—The Jew of Venice—may reflect Shylock’s impact on the play’s first audiences.

The play is constructed on the basis of two romantic tales using motifs well known to sixteenth-century readers. The story of Giannetto (Shakespeare’s Bassanio) and the Lady (Portia) of Belmont comes from an Italian collection of fifty stories published under the title of II Pecorone (‘the big sheep’, or ‘dunce’) and attributed to one Ser Giovanni of Fiorentino. Written in the later part of the fourteenth century, the volume did not appear until 1558. No sixteenth-century translation is known, so (unless there was a lost intermediary) Shakespeare must have read it in Italian. It gave him the main outline of the plot involving Antonio (the merchant), Bassanio (the wooer), Portia, and the Jew (Shylock). The pound of flesh motif was available also in other versions, one of which, in Alexander Silvayn’s The Orator (translated 1596), influenced the climactic scene (4.1) in which Shylock attempts to exact the full penalty of his bond.

In the story from II Pecorone the lady (a widow) challenges her suitors to seduce her, on pain of the forfeiture of their wealth, and thwarts them by drugging their wine. Shakespeare more romantically shows a maiden required by her father’s will to accept only a wooer who will forswear marriage if he fails to make the right choice among caskets of gold, silver and lead. The story of the caskets was readily available in versions by John Gower (in his Confessio Amantis) and Giovanni Boccaccio (in his Decameron), and in an anonymous anthology (the Gesta Romanorum). Shakespeare added the character ofJessica, Shylock’s daughter who elopes with the Christian Lorenzo—perhaps influenced by episodes in Christopher Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta (c.1589)—and made many adjustments to the stories from which he borrowed.

The Merchant of Venice is a natural development from Shakespeare’s earlier comedies, especially The Two Gentlemen of Verona, with its heroine disguised as a boy and its portrayal of the competing demands of love and friendship. But Portia is the first of his great romantic heroines, and Shylock his first great comic antagonist. Though the play grew out of fairy tales, its moral scheme is not entirely clear cut: the Christians are open to criticism, the Jew is true to his own code of conduct. The response of twentieth-century and later audiences has been complicated by racial issues; in any case, the role of Shylock affords such strong opportunities for an actor capable of arousing an undercurrent of sympathy for a vindictive character that it has sometimes unbalanced the play in performance. But the so-called trial scene (4.1) is unfailing in its impact on audiences, and the closing episodes modulate skilfully from romantic lyricism to high comedy, while sustaining the play’s concern with true and false values.

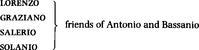

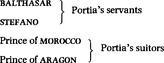

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

ANTONIO, a merchant of Venice

BASSANIO, his friend and Portia’s suitor

LEONARDO, Bassanio’s servant

SHYLOCK, a Jew

JESSICA, his daughter

TUBAL, a Jew

LANCELOT, a clown, first Shylock’s servant and then Bassanio’s

GOBBO, his father

PORTIA, an heiress

NERISSA, her waiting-gentlewoman

DUKE of Venice

Magnificoes of Venice

A jailer, attendants, and servants

The Comical History of the Merchant of Venice, or Otherwise Called the Jew of Venice

1.1 Enter Antonio, Salerio, and Solanio

ANTONIO

In sooth, I know not why I am so sad.

It wearies me, you say it wearies you,

But how I caught it, found it, or came by it,

What stuff ’tis made of, whereof it is born,

I am to learn;

And such a want-wit sadness makes of me

That I have much ado to know myself.

SALERIO

Your mind is tossing on the ocean,