Theobald claimed to own several manuscripts of an original play by Shakespeare, and remarked that some of his contemporaries thought the style was Fletcher’s, not Shakespeare’s. When he himself came to edit Shakespeare’s plays he did not include either Double Falsehood or the play on which he claimed to have based it; he simply edited the plays of the First Folio, not adding either Pericles or The Two Noble Kinsmen, though he believed they were partly by Shakespeare. It is quite possible that Double Falsehood is based (however distantly) on a play of Shakespeare’s time; if so, the play is likely to have been the one performed by the King’s Men and ascribed by Moseley in 1653 to Fletcher and Shakespeare.

Double Falsehood is a tragicomedy; the characters’ names differ from those in Don Quixote, and the story is varied. Henriquez rapes Violante, then falls in love with Leonora, loved by his friend Julio. Her parents agree to the marriage, but Julio interrupts the ceremony. Leonora (who had intended to kill herself) swoons and later takes sanctuary in a nunnery. Julio goes mad with desire for vengeance on his false friend; and the wronged Violante, disguised as a boy, joins a group of shepherds, and is almost raped by one of them. Henriquez’s virtuous brother, Roderick, ignorant of his villainy, helps him to abduct Leonora. Leonora and Violante both denounce Henriquez to Roderick. Finally Henriquez repents and marries Violante, while Julio (now sane) marries Leonora.

Some of the motifs of Double Falsehood, such as the disguised heroine wronged by her lover and, particularly, the reuniting and reconciliation of parents with children, recall Shakespeare’s late plays. But most of the dialogue seems un-Shakespearian. Though the play deserved its limited success, it is now no more than an interesting curiosity.

ALL IS TRUE

(HENRY VIII)

BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE AND JOHN FLETCHER

ON 29 June 1613 the firing of cannon at the Globe Theatre ignited its thatch and burned it to the ground. According to a letter of 4 July the house was full of spectators who had come to see ‘a new play called All is True, which had been acted not passing two or three times before’. No one was hurt ‘except one man who was scalded with the fire by adventuring in to save a child which otherwise had been burnt’. This establishes the play’s date with unusual precision. Though two other accounts of the fire refer to a play ‘of’—which may mean simply ‘about’—Henry VIII, yet another two unequivocally call it All is True; and these words also end the refrain of a ballad about the fire. When the play came to be printed as the last of the English history plays—all named after kings—in the 1623 Folio it was as The Famous History of the Life of King Henry the Eighth. We restore the title by which it was known to its first audiences.

No surviving account of the fire says who wrote the play that caused it. In 1850, James Spedding (prompted by Tennyson) suggested that Shakespeare collaborated on it with John Fletcher (1579-1625). We have external evidence that the two dramatists worked together in or around 1613 on the lost Cardenio and on The Two Noble Kinsmen. For their collaboration in All is True the evidence is wholly internal, stemming from the initial perception of two distinct verse styles within the play; later, more rigorous examination of evidence provided by both the play’s language and its dramatic technique has convinced most scholars of Fletcher’s hand in it. The passages most confidently attributed to Shakespeare are Act 1, Scenes 1 and 2; Act 2, Scenes 3 and 4; Act 3, Scene 2 to line 204; and Act 5, Scene 1.

The historical material derives, often closely, from the chronicles of Raphael Holinshed and Edward Hall, supplemented by John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563, etc.) for the Cranmer episodes in Act 5. It covers only part of Henry’s reign, from the opening description of the Field of the Cloth of Gold, of 1520, to the christening of Princess Elizabeth, in 1533. It depicts the increasing abuse of power by Cardinal Wolsey; the execution, brought about by Wolsey’s machinations, of the Duke of Buckingham; the King’s abandonment of his Queen, Katherine of Aragon; the rise to the King’s favour of Anne Boleyn; Wolsey’s disgrace; and the birth to Henry and Anne of a daughter instead of the hoped-for son.

Sir Henry Wotton, writing of the fire, said that the play represented ‘some principal pieces of the reign of Henry 8, which was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and majesty’. It has continued popular in performance for the opportunities that it affords for spectacle and for the dramatic power of certain episodes such as Buckingham’s speeches before execution (2.1), Queen Katherine’s defence of the validity of her marriage (2.4), Wolsey’s farewell to his greatness (3.2), and Katherine’s dying scene (4.2). Though the play depicts a series of falls from greatness, it works towards the birth of the future Elizabeth I, fulsomely celebrated in the last scene (not attributed to Shakespeare) along with her successor, the patron of the King’s Men.

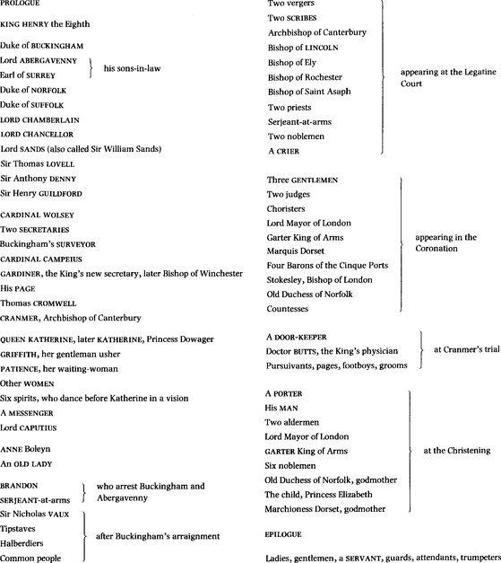

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

All Is True

Prologue Enter Prologue

PROLOGUE

I come no more to make you laugh. Things now

That bear a weighty and a serious brow,

Sad, high, and working, full of state and woe—

Such noble scenes as draw the eye to flow

We now present. Those that can pity here

May, if they think it well, let fall a tear.

The subject will deserve it. Such as give

Their money out of hope they may believe,

May here find truth, too. Those that come to see

Only a show or two, and so agree

The play may pass, if they be still, and willing,

I’ll undertake may see away their shilling

Richly in two short hours. Only they

That come to hear a merry bawdy play,

A noise of targets, or to see a fellow

In a long motley coat guarded with yellow,

Will be deceived. For, gentle hearers, know

To rank our chosen truth with such a show

As fool and fight is, beside forfeiting

Our own brains, and the opinion that we bring

To make that only true we now intend,

Will leave us never an understanding friend.

Therefore, for goodness’ sake, and as you are known

The first and happiest hearers of the town,

Be sad as we would make ye. Think ye see

The very persons of our noble story

As they were living; think you see them great,

And followed with the general throng and sweat