‘What was his name?’

Gerrit frowned. Illness had slowed him down and it took a moment to drag the name up from his memory. ‘Guillaine … Oh, fuck!’ he said incredulously. ‘I don’t believe it.’

‘What?’

‘… I never made the connection …’

‘What?’

‘… Sabine Monette’s maiden name was Guillaine.’

Sixty

Rain again. Rain and more rain, leaving the capital waterlogged, the monuments spotted. Along St James’s Street, people walked with their heads down, umbrellas held against the wind like a phalanx of Spartan shields. And it kept on raining as Carel Honthorst crossed over and continued to follow Nicholas. The Dutchman hated rain. He was always afraid that it would dislodge his concealer, send it sliding down into his collar like a beige tsunami. Rain made him mean.

He had despised Nicholas Laverne for a long time, ever since Laverne had gone public and exposed the abuse at St Barnabas’s church. He might not be an active priest any longer, but the Dutchman held his religion in awe. To Honthorst – whose only security was the Church – any criticism was treachery. He would have stayed a priest, because he had found the religious life easy, but he hadn’t found the other priests easy. He didn’t find the politics comfortable either. Seeking succour and simplicity, Honthorst had run away from a tough childhood into the arms of Mother Church. But her arms had been less loving than he had imagined and her caresses less forthcoming than he had hoped.

Never popular, Honthorst found himself pulling away from the Church, his natural viciousness re-emerging as he felt himself cheated of salvation. It was not the Church’s fault, it was his. His violent nature was too engrained to forgo, his pleasure in inflicting pain too seductive to relinquish. Confession absolved him, but only for so long. The incense and the candles worked on his senses like a sedative, the red light of the incense burner the eye of a demon staring down at him in his pew. The eye seemed to say he was fooling no one, blinking in the church and puffing out little breaths of smoke like a dying cat. Honthorst would grip the altar rail and take the Sacrament, but as time passed the wafer stuck like a blister to the roof of his mouth and the wine poisoned him.

It was all his fault – he knew that. So he left his life as a priest and took up debt collecting, relishing a legal excuse for brutality. His life split like a rotten apple: on one side religion, on the other violence. And he developed a hatred of anyone who spoke out against the Church. Honthorst might not fit in, but he would brook no criticism. So when Mother Church opened up her arms to him, needing his help, Honthorst went back in.

Walking quickly, the Dutchman saw Nicholas cross over the street and began to follow him, always keeping a little distance behind. Finally he saw Nicholas enter an old building set in an alleyway off the main street. The place was haphazardly built on three floors and seemed virtually empty. Honthorst checked his watch: six thirty, well past closing time for businesses. Curious, he looked through the window and watched as Nicholas spoke to a stout middle-aged man on the ground floor. The man listened, then together they entered a cramped, old-fashioned lift.

Hurrying round to the back of the building, Honthorst took a moment to get his bearings, then clambered up the fire escape. The two men were directly in his line of sight and he drew back to avoid being seen. He could hear murmured conversation, and then watched as the middle-aged man nodded and descended in the lift again. A few moments passed, but when the man didn’t return and no one else came in, Honthorst tried the window. It was unlocked. Climbing in, he moved quietly across the landing and glanced through a half-opened door.

He could see that it was some kind of sitting room, but there was a computer in there and a drawing board with sketches lying on it. A moment later Nicholas came into view, reading the paper. Honthorst sniffed the air like a gun dog. He was tired of holding back. Frighten him, they had said, ratchet up the tension, but Honthorst wanted more. And now he was in the perfect position to get it.

Slowly he pushed the door open. But Nicholas had left the room by an adjoining door and was back on the landing. Retracing his steps, Honthorst heard the sound of the lift rising upwards and then the metal grille being drawn back. In that instant he lunged forward, catching Nicholas off guard. But he recovered fast, getting into the lift and pulling the Dutchman’s arm through the grille as he slammed it shut.

‘What d’you want from me?’ Nicholas asked as Honthorst struggled to free himself. But his sleeve had caught on the grille and that, together with Nicholas’s grip, held him fast.

‘Let me go!’

‘You’ve been following me. What for?’

‘I work here—’

‘No, you don’t. I know everyone who works here and you don’t. Remember, I saw you at Philip Preston’s—’

‘You’re breaking my arm!’

‘So relax,’ Nicholas said, his tone lethal. ‘Who sent you?’

‘No one.’

‘What do they want you to do? Kill me?’

‘I’m not after you. No one sent me!’ Honthorst gasped, watching as Nicholas put his finger on the lift button.

‘Tell me who sent you or I press this. The lift will pull your bloody arm off—’

‘No one sent me!’ Honthorst screamed, scrabbling to free himself.

‘One last chance – who was it?’

‘Go to Hell!’ Honthorst shouted, trying to grab Nicholas and missing. ‘I’ll get you. I swear I’ll kill you, you bastard—’

The lift started to descend the moment Nicholas pressed the button. The noise was deafening, but even over the machinery, he could hear the sound of the arm breaking, Honthorst screaming as his limb was torn out of its socket.

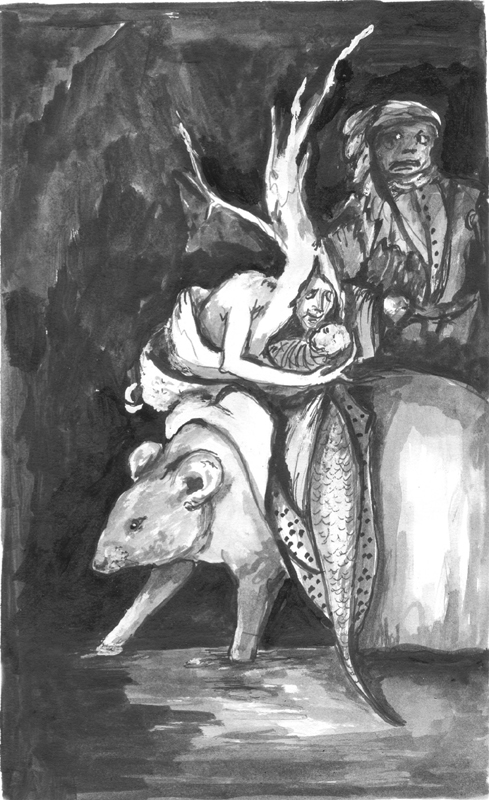

‘The Temptation of St Anthony’ [detail]

After Hieronymus Bosch

’s-Hertogenbosch, Brabant, 1473

Dawn was holding back, coming slow and heavy with mist as Hieronymus turned over in his bed and slowly got to his feet. After he had been brought back to ’s-Hertogenbosch he had been watched constantly, the studio door only unlocked when food was brought in. As the church clock struck nine the timid Goossen entered, carrying a tray of food.

As ever, he mumbled apologies and tried not to look at his brother.

‘Ignore him, Goossen,’ Antonius had said, perpetuating the lie he had preached for years. ‘Don’t say a word to your brother. He’s possessed. We have to look after him. We have to keep him safe.’

But Goossen had never believed what his father had said. Too scared to stand up to the formidable Antonius, he had defied him in small ways. He had smuggled in treats for Hieronymus, slipping heavy Dutch fruit loaves into the basket of paint pigments. Sometimes he had even managed to secrete a little beer, but after his father had found out, the baskets were always searched.

In silence, Goossen watched his brother paint the head of a fish with a man’s body.

‘What is it?’

‘What I dream,’ Hieronymus replied, pausing.

For a moment he was tempted to ask for help, to appeal to his brother to aid him with another attempt at escape. But he remained silent. He was sick in the lungs, coughing, spitting up blood red as the cadmium paint on his palette. Blood like the red of the devils in his paintings, blood like the colour of the flames of Hell. He was tired. Too tired to plot or to escape. Too tired to live. He would have liked to talk more, but Goossen merely touched his shoulder and left. A moment later, Hieronymus heard the lock turn in the door.