Hieronymus wondered what the merchant would say if he knew he had been sketched, his image put aside to serve as a fat demon in a painting of Hell. Hieronymus liked to steal images, sitting in his studio at the top of the house and watching the market-place with its press of people. From his eyrie he caught sight of pickpockets and whores baring their breasts to attract trade. They wore woollen chemises tied at the neck, easy to undo.

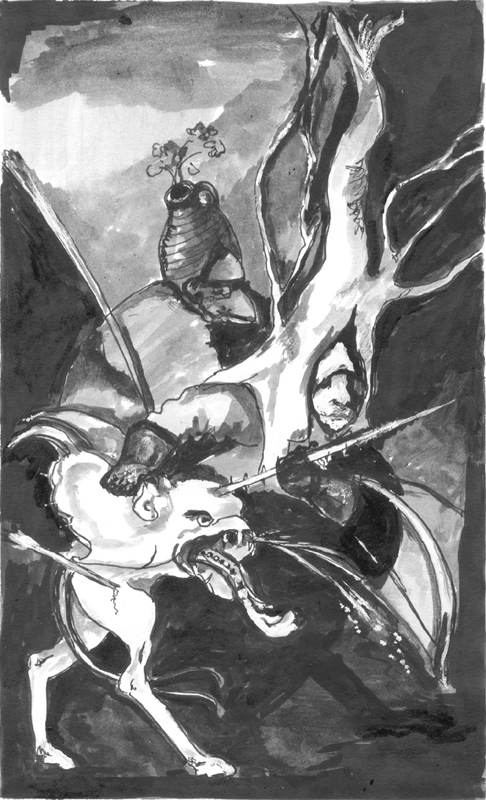

‘The Temptation of St Anthony’ [detail]

After Hieronymus Bosch

And then there were the dealers, the merchants who had profited from the flourishing wool and textile industries of Brabant, the dukes of Brabant depending on the wealth created to finance their wars and extravagant lifestyles. The towns were rich, fat on trade, and with that trade – alongside discoveries by seafarers and scientists – came the sobering influence of religion.

Hieronymus paused to watch a dog barking loudly at a penned pig as a boy poked it with a stick. For a moment he was tempted to draw the boy, but he moved on towards the church. His success had overwhelmed him; not yet twenty, he was pointed out at the market, hailed on the street. His father and brothers would have adored such attention but for Hieronymus, shy, crippled by night terrors and afraid of the world around him, it was torment. He felt at peace only in the privacy of his studio, paintbrush in hand.

Antonius might brag of his son in public, but in private he was a critical, belittling tyrant, his hatred of Hieronymus stemming from the death of his wife during the birth of this, their last child. Indeed, if the boy had not turned out to be so gifted he might well have been shipped off to a cousin in the country, forgotten and unmourned.

But for all Antonius’s dislike of his son, Hieronymus’s talent protected him. Its early flowering appeared like an orchid in a dunghill, provoking awe. As the boy’s promise developed into an outstanding talent, Antonius touted him about the Brotherhood like a prize ram with a fleece that could be stripped and woven into gold. In the runt of the family, the ambitious and pious Antonius saw his own reputation advancing, his family coffers swelling.

It was fortunate that his son had such nightmares, dreams of Hell and damnation which Antonius’s treatment had exacerbated over the years. His criticism and judgemental attitude had cowed the boy; buckled the genius into a haunted wrath. But the mistreatment had also resulted in a vision, which the Church recognised and devoured. Hieronymus’s paintings portrayed everyday life at a time when religion wielded a moral cosh to keep people in line. Urged on by the Church and his father, he was corralled into depicting themes of temptation, sin and punishment. The Devil that the priests thundered about lived in his paintings and their message was simple: a good life leads to Heaven, a sinful one to Hell.

But the hallucinations and night terrors Hieronymus suffered from affected his health. When the plague came to Europe, he was protected, the studio door locked and visitors turned away. His family monitored his sleeping, his eating, his walks in the walled garden. If their breadwinner sickened or died, so would their fortunes. And so the Church and his own family pressed him into work, into the endless service of his terrifying visions.

And then, one day in May of 1473, Hieronymus Bosch escaped.

Twenty-Six

Eloise Devereux stood for a moment outside the gallery in Chelsea, then opened the door and walked in. Her attractive presence soon caught the attention of Miriam der Keyser. A thin woman with a whining voice, she patrolled her husband’s gallery like a jailer, his every conversation with a woman supervised.

‘Can I help you?’ Miriam asked peevishly.

‘Is your husband here? I’d like to speak to Mr der Keyser.’

Miriam’s mouth opened, but before she could speak Gerrit materialised at the back of the gallery. ‘Can I be of assistance?’ he asked, darting his wife a dismissive look.

‘I’d like to talk to you in private,’ Eloise continued. ‘It’s a confidential matter.’

‘My husband’s busy—’ Miriam tried to interrupt but Gerrit brushed past her and led Eloise into his office. Once inside, he made sure the door was closed and Miriam on the outside.

‘How can I help?’

He was all servile charm, using the gallant persona reserved for his customers. And she was quite a customer, he thought, watching as Eloise sat down and crossed her legs.

‘You’re doing well,’ she remarked coolly. ‘I liked the David Teniers in the window. I know how much you admire that artist.’

His collar felt suddenly tight, an unpleasant sensation rising in him. Gerrit didn’t recognise the woman, but she was talking to him as though they were old acquaintances.

‘Do I know you?’

She ignored the question, glancing around the office, Her hair swept up in a chignon, her cream coat cut to perfection, elegance exuded from her. Gerrit fiddled with his over-large cuffs then reached into his desk drawer and took out a bottle of pills. Without a word, he swallowed several with a glass of water, Eloise watching him.

‘You’re ill, but I suspected as much. You’ve lost a lot of weight – you used to be a stocky man.’ She paused, putting her head to one side. ‘You don’t know who I am, do you?’

He shook his head. ‘No, I don’t. Who are you?’

‘We’ll come to that later,’ she replied. ‘I have some business to discuss first: a chain which once belonged to Hieronymus Bosch.’ Gerrit’s eyes flickered. Eloise noted the reaction and smiled. ‘I can imagine how much you must want to get it back. It was unusual for you to be slow and lose it. But then again, illness slows everyone down.’

‘OK, what the fuck’s going on?’ Gerrit asked, all politeness abandoned.

‘I know you’re looking for the chain.’ Her eyes held his gaze. ‘How hard are you looking?’

‘Sabine Monette stole it off a painting—’

‘And now Sabine Monette is dead,’ Eloise replied. ‘Are the two connected?’

‘She died in Paris, in the George the Fifth Hotel. Some fucking lunatic killed her—’

‘Why did he kill her? Her money wasn’t taken.’

‘How come you know so much about it?’ Gerrit asked, his eyes narrowing. ‘This has nothing to do with me—’

‘It has everything to do with you. You wanted that chain, you threatened Sabine Monette—’

‘I did not!’

She waved aside his protestations. ‘All right, you sent some thug to threaten her. Either way, she ended up dead. Murdered.’

Gerrit rose to his feet. ‘I don’t have to talk to you.’

‘You’re right, you don’t. But if you want to get the chain back, maybe you should,’ she replied. ‘Maybe I can get it for you.’

He was all attention now, regaining his seat and running his tongue over his bottom lip. ‘Why would you?’

‘I have my reasons.’

‘Which are?’

‘Nothing to do with you,’ she replied coolly. ‘Do you want the chain back?’

‘How much?’

‘It’s not about money, Mr de Keyser, it’s much more valuable than that. This is about a debt. One you owe someone I cared about … Let me tell you something. My husband, my dead husband, had a friend who was in trouble. That friend went to work for an elderly lady in France, Sabine Monette. I knew about it because I was close to Sabine and she confided in me. I thought the relationship would be good for both of them. And it was.’

‘What the hell—’

‘Hear me out – it’s in your interests,’ she admonished him. ‘You had an affair with Sabine Monette many years ago. It was brief and unhappy, or so she told me.’ Eloise was perfectly poised. ‘I suppose I should mention that I inherited a large fortune when I reached eighteen.’