Hayek himself criticized Keynesian policies as collectivist and never temporary. Perhaps Austrian school economist Joseph Schumpeter, who coined the term “creative destruction,” summed up its point of view best in 1934: “Recovery is sound only if it does come of itself.”

Why You Should Care

The Austrian school may seem radical, perhaps radically conservative, and almost antigovernment in nature. That said, many of the symptoms proponents talk about, and much of their analysis of the Great Depression, resonates. It should help you maintain a healthy skepticism of government action, though most economists don’t go this far in condemning the role of government. As an individual, it helps to have a balanced view of what’s going on, and to understand the upsides and downsides of any government intervention. By the way, Austrian school disciple Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression, Sixth Edition (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011) is a fascinating read if you enjoy this sort of thing.

60. SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS

Capitalism is founded on the notion that people produce goods and services under their own free will, and that they earn the appropriate rewards for their achievement. Supply-side economics extends this fundamental school of thought by arguing that the best way to achieve economic growth is by maximizing the incentive to produce, or supply goods and services. That’s best done by reducing taxes and regulation, allowing the greatest rewards, and allowing those goods to flow to market at the lowest possible prices.

What You Should Know

The term “supply-side economics” is relatively recent, coming into the language in the mid 1970s. Supply-side economics spawned close cousins in the form of “trickle-down economics” (see #61) and Reaganomics (see #62); all three members of this happy family got a good test in the 1980s in the administration of Ronald Reagan.

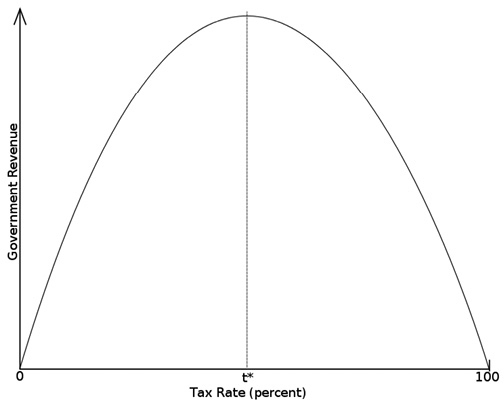

Supply-side economics attempts to optimize tax rates—that is, marginal tax rates, or rates paid on the highest dollar earned. The optimization is achieved by setting the tax rate low enough to avoid discouraging individual production and earning, but high enough to encourage enough production and earning to maximize total tax revenues. That in turn offsets the potential loss in tax revenue by lowering the tax rates. Stated differently, the tax rate matters more to individuals, total taxes collected matters more to government.

The relationship between tax rates and total tax revenue is illustrated in Figure 6.1. The Laffer Curve is named for economist Arthur Laffer, the supply-side proponent who created it.

Figure 6.1 Laffer Curve

Source: Wikimedia commons, free license

The contrast between supply-side economics and other schools is illustrated by comparison with the Keynesian school, which contends that tax cuts should be used to create demand, not supply. The Keynesian school, by implication, would target the tax cuts toward lower-income earners who are most likely to spend, while the supply-sider would target them toward the higher-income earners, and especially business owners and leaders paying the highest tax rates. Doing so would stimulate the greatest increases in production; if these individuals faced 50 or even 70 percent tax rates, they would be less inclined to produce more and earn more (see #47 Tax Policy). The other end of the supply-side equation holds that the resulting economic growth from stimulated supply would make up for the loss in tax revenue.

The jury is still out on the effects of the supply-side “test” in the 1980s. Significant decreases in marginal tax rates were enacted and production did expand through the 1980s; the economy emerged from the Reagan administration far healthier than when he took office, even with the 1987 stock market crash. However, sufficient revenue was never generated to cover the tax decreases; the deficit grew persistently. That may have been caused more by increases in defense spending and other government programs than a failure in supply-side economics. Additionally, increased income inequality (the rich get richer, etc.) has also been a nagging criticism of supply-side policies.

More recently, supply-side economics has definitely been in the minds of the so-called “Tea Party” and other tax conservatives who believe even a slight increase (from 36 percent to 39.6 percent rates for top earners) tips the balance, but in effect through raises in Medicare taxes, capital gains taxes, and income taxes in many states, tax rates for the wealthy are going up anyway. Revenues have gone up considerably since the Great Recession, but still not enough to offset economic stimulus, spending increases, and growing entitlements (Social Security and Medicare). As such, the supply-side school has yet to fully prove itself, but there is a general feeling that things would be much worse if it had never come into play.

Why You Should Care

As an individual, particularly as an economically productive individual, you should favor the supply-side approach. It carries greater economic rewards for achievement, and makes hard work and investment more attractive. But before “buying” this approach from the politicians, make sure that the other end of the equation—government expenditures—are held in check. Otherwise, the additional tax revenues generated will not be sufficient and deficits will endure, putting America in a fundamental “box” of not being able to raise taxes if necessary. This mistake of the Reagan administration, and later the George H.W. Bush administration policy of “no new taxes,” took a lot of wind out of the sails of this promising approach. We saw it again in the second Bush administration, and though attenuated somewhat under Obama, the general concept remains in play.

61. TRICKLE-DOWN ECONOMICS

The “trickle-down” school of economics carries a set of principles and actions very similar to supply-side economics (see #60), but the goal is different. While the supply-side school advocates stimulating production to benefit the economy as a whole and pay for the tax rate decreases that stimulated the production, the trickle-down school goes on to argue that increased production and wealth accumulated at the top will eventually “trickle down” to the masses.

What You Should Know

The premise is based on the idea that more prosperous business owners and leaders will produce more and take more risks, providing jobs and higher incomes for the masses. Additionally, the supply-side premise that greater production at a lower cost will lead to lower prices for consumers also suggests better standing for the lower economic tiers of society. Trickle-down economics takes the supply-side approach and extends it to a premise and promise of greater societal benefit for everyone.

The problem, of course, is that the wealth created at the top doesn’t always trickle down so effectively. Many believe that quite the opposite happens—that the rich get richer, and not very much happens to anyone else. As William Jennings Bryan put it in the 1890s: “If you legislate to make the masses prosperous, their prosperity will find its way up through every class which rests upon them.”

Indeed, the trickle-down theory was never directly advocated by the Reagan and Bush leadership, but was a constant theme in the congressional debates on tax policy, which went something like this: The wealthy will get what they want, the budget will be balanced on the back of higher tax revenues, and it will help the lower classes too. Unfortunately, the second two parts of the scenario never really played out—government spending exceeded the new revenues, and the wealthy chose to keep a lot of their wealth. By almost any measure, the wealthy got wealthier through the period. Why that happened is a matter of conjecture. First, lower tax rates and especially capital gains tax rates encouraged them to save it for themselves, not create new production and thus jobs; or second, in the face of an economy where considerable production was moving overseas, there wasn’t enough job-creating activity to invest in.