BOOK FOUR

THUNDERBOLT

OCTOBER 1905

CONSTABLE HOOK

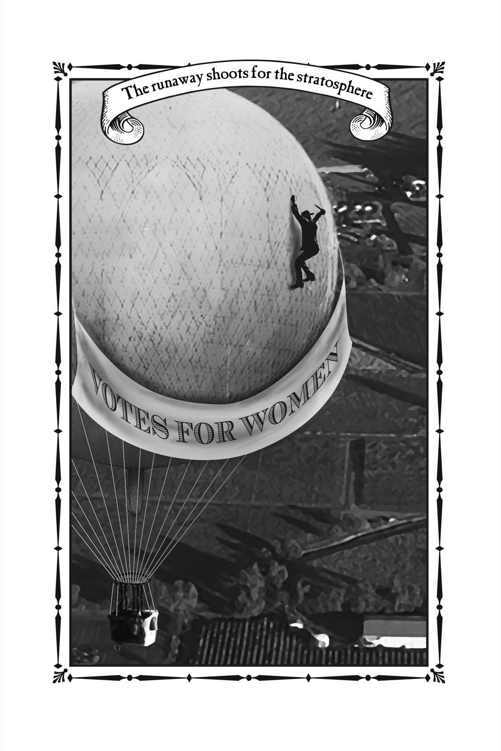

Nellie Matters’ runaway gas balloon shot skyward, lofting Isaac Bell toward the stratosphere where the air was too thin to breathe. The other colorful Flyover balloons, so enormous an instant ago, suddenly looked tiny, dotting the Sleepy Hollow field like a game of marbles. A white circle in the green grass marked the spot Nellie had dumped the sand.

Bell thought he saw her running to another partially inflated balloon. But with no ballast left to counteract the urgent lift of the lighter-than-air gas, he was too high up in another second to distinguish individual figures, so high he could see Rockefeller’s estate spread to the Hudson River. He heard a locomotive and realized that the only noises were from the ground; after the initial roar of extra gas, the balloon was ascending silently. A New York–bound passenger train, the crack Lakeshore Limited, was heading for the North Tarrytown railroad station towing two black cars. They would be chartered by Rockefeller, who was returning from Cleveland with his entire family, and Isaac Bell had the momentary satisfaction of knowing that whether or not he got out of this fix, he had at least stopped Nellie Matters from shooting the old man this morning.

The only way to stop his wild ascent was to release gas.

Bell traced the control lever wires. The ballast wire that went down through the bottom of the basket was useless, as Nellie had already dumped every grain of sand. Of the two that went up into the mouth of the giant gasbag, one connected to a “rip panel” at the top of the balloon. Nellie had explained more than once, while spinning her balloon tales, that pulling that lever would tear the fabric envelope wide open and release all the gas at once. It was an emergency device for instantly emptying the balloon when it was on the ground to keep high winds from dragging it into the trees or telegraph wires. To pull the rip panel lever at this height would be to fall like an anvil.

The wire broken by the bullet that had missed Nellie turned out to be the gas control. It had snapped inches above the lever. Looking up eighty feet, Bell could see the business end was still attached to the release flap in the dome at the top of the balloon. Parting while under tension, it had sprung up into the mouth. He could see it swinging inside the empty gasbag, tantalizingly near but infinitely far out of reach. There was no framework to climb inside the balloon—the gas pressing against the fabric envelope gave it shape—but even if it had a frame that he could improvise for a ladder, the gas would asphyxiate him before he climbed ten feet.

He jumped onto the rim of the rattan basket and shinnied up a bask rope to the steel load ring. Hanging by one hand, he caught ahold of the ropes that were woven into the enormous net that encased the bulging envelope like a giant spiderweb. Then he reached down for the knife snugged in his boot. He touched the blade to the straining fabric to slash an opening to vent gas.

He felt a breath of cool air for the first time in a week. The balloon had carried him above the heat wave into a cold current in the upper atmosphere, and he saw he hadn’t a moment to lose. The patchwork of farm fields far below appeared to be moving. The blue line of the Hudson River was receding behind him. Wind that Nellie had predicted was carrying him east over Connecticut.

But just as he braced to press down on the blade, it struck him forcibly that there were vital aeronautical reasons why both the regular gas release and the emergency rip panel were situated at the top of the balloon. He drove his hand between that rope and the fabric to overcome the pressure inside it and pulled himself higher up by the netting ropes until he could brace his feet on the load ring.

Like a celestial giant climbing from the earth’s South Pole to the North Pole, he worked his way up and out, hanging almost horizontally from the web, as the bulge of the globe-shaped balloon spread from the narrow mouth at the bottom toward the Equator.

He climbed some forty feet as it swelled wider and wider. Then he climbed gradually into a vertical stance as he crossed the Equator at the widest part of the balloon.

When he glanced down, he saw the silvery waters of the Long Island Sound riddled with white sails and streaked by steamer smoke. He glimpsed the sand bluffs of the North Shore of Long Island and realized that the balloon had risen up into a more powerful air current. In its grip, he was traveling rapidly. And the balloon was still climbing. The farms appeared smaller and smaller, and the clusters of towns gave the illusion of growing closer to one another as it gained altitude.

Past the equatorial bulge, he was able to move faster, scrambling to get to the top, tiring from the effort, but driven by an arresting sight: the balloon was now so high that he could see the green back of the twenty-mile-wide Long Island and, beyond it, the deep blue waters of the Atlantic Ocean. If he didn’t suffocate in the stratosphere, the ocean would be waiting below.

He reached the dome, the top of the gas envelope, drew his throwing knife from his boot, and plunged it into the fabric. In the strange silence, the hiss of gas escaping under enormous pressure was deafening. It blasted from the small slit he had cut. But he felt no effect, no indication that the balloon had ceased to climb, much less begun to sink. He dragged the sharp blade through more fabric, skipping over the netting, lengthening the slit, hunting the ideal size to reduce the lift of gas so the balloon would descend quickly but still float.

He felt light-headed. His foot slipped from the rope web. His hands were losing their grip. The knife started to slide from his fingers. The gas! He suddenly realized the gas was jetting past his face and he was inhaling it, breathing it into his lungs, slipping under the edge of consciousness. He ducked his face below the slit and held on with all his fading strength. It was getting worse. His head was spinning. He gathered his will and dropped down a row of rope netting and sucked in fresh air. When he could see straight again, he reached overhead with the knife and slashed more holes in the fabric.

There were thousands of cubic feet of lighter-than-air gas lifting the balloon. How much did he have to let out to make it sink? He recalled Nellie describing a fine line to calculate the balance between the weight to be lifted and the volume of gas. He heard a ripping sound and looked up. The fabric between the two slits he had cut was tearing, joining the slits, and suddenly the gas was rushing from the united fissure.

Bell’s stomach lurched. He thought for a moment that the gas was making him sick. Then he realized the balloon had lost all buoyancy and was plummeting back to earth.

—

With no way to control the release, Isaac Bell’s only hope was to climb down to the basket and throw everything over the side to reduce the weight dragging the balloon back to earth before it collapsed. Retracing his ascent, hand under hand, boot under boot, he slipped from cross rope to cross rope, down toward the middle bulge as fast as he could.

Was the bag less taut? No doubt about that. The fabric had ceased to press so hard against the net. He looked down. He saw the farms. He saw the silver Sound and Long Island shore. But the balloon had fallen so far that he was no longer high enough to see the ocean.