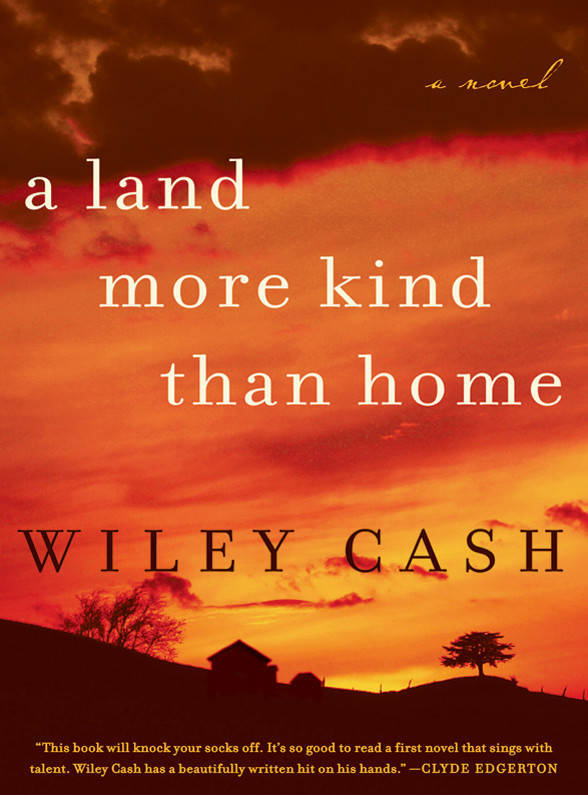

Wiley Cash

DEDICATION

M.B.C.

FOR YOU, BECAUSE OF YOU

EPIGRAPH

Something has spoken to me in the night … and told me

I shall die, I know not where. Saying:

“[Death is] to lose the earth you know, for greater knowing; to lose the life you have, for greater life; to leave the friends you loved, for greater loving; to find a land more kind than home, more large than earth.”

—THOMAS WOLFE, YOU CAN’T GO HOME AGAIN

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Adelaide Lyle

ONE

Jess Hall

TWO

THREE

Clem Barefield

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

Jess Hall

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

Clem Barefield

ELEVEN

Adelaide Lyle

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

Clem Barefield

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

Jess Hall

NINETEEN

TWENTY

Adelaide Lyle

TWENTY-ONE

Clem Barefield

TWENTY-TWO

Jess Hall

TWENTY-THREE

Clem Barefield

TWENTY-FOUR

Adelaide Lyle

TWENTY-FIVE

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Adelaide Lyle

O

NE

I SAT THERE IN THE CAR WITH THE GRAVEL DUST BLOWING ACROSS the parking lot and saw the place for what it was, not what it was right at that moment in the hot sunlight, but for what it had been maybe twelve or fifteen years before: a real general store with folks gathered around the lunch counter, a line of people at the soda fountain, little children ordering ice cream of just about every flavor you could think of, hard candy by the quarter pound, moon pies and crackerjack and other things I hadn’t thought about tasting in years. And if I’d closed my eyes I could’ve seen what the building had been forty or fifty years before that, back when I was a young woman: a screen door slamming shut, oil lamps lit and sputtering black smoke, dusty horses hitched to the posts out front where the iceman unloaded every Wednesday afternoon, the last stop on his route before he headed up out of the holler, the bed of his truck an inch deep with cold water. Back before Carson Chambliss came and took down the advertisements and yanked out the old hitching posts and put up that now-yellow newspaper in the front windows to keep folks from looking in. All the way back before him and the deacons had wheeled out the broken coolers on a dolly, filled the linoleum with rows of folding chairs and electric floor fans that blew the heat up in your face. If I’d kept my eyes closed I could’ve seen all this lit by the dim light of a memory like a match struck in a cave where the sun can’t reach, but because I stared out through my windshield and heard the cars and trucks whipping by on the road behind me, I could see now that it wasn’t nothing but a simple concrete block building, and, except for the sign out by the road, you couldn’t even tell it was a church. And that was exactly how Carson Chambliss wanted it.

As soon as Pastor Matthews caught cancer and died in 1975, Chambliss moved the church from up the river in Marshall, which ain’t nothing but a little speck of town about an hour or so north of Asheville. That’s when Chambliss put the sign out on the edge of the parking lot. He said it was a good thing to move like we did because the church in Marshall was just too big to feel the spirit in, and I reckon some folks believed him; I know some of us wanted to. But the truth was that half the people in the congregation left when Pastor Matthews died and there wasn’t enough money coming in to keep us in that old building. The bank took it and sold it to a group of Presbyterians, just about all of them from outside Madison County, some of them not even from North Carolina. They’ve been in that building for ten years, and I reckon they’re proud of it. They should be. It was a beautiful building when it was our church, and even though I ain’t stepped foot in there since we moved out, I figure it probably still is.

The name of our congregation got changed too, from French Broad Church of Christ to River Road Church of Christ in Signs Following. Under that new sign, right out there by the road, Chambliss lettered the words “Mark 16:17–18” in black paint, and that was just about all he felt led to preach on too, and that’s why I had to do what I done. I’d seen enough, too much, and it was my time to go.

I’d seen people I’d known just about my whole life pick up snakes and drink poison, hold fire up to their faces just to see if it would burn them. Holy people too. God-fearing folks that hadn’t ever acted like that a day in their lives. But Chambliss convinced them it was safe to challenge the will of God. He made them think it was all right to take that dare if they believed. And just about the whole lot of them said, “Here I am, Lord. Come and take me if you get a mind to it. I’m ready if you are.”

And I reckon they were ready, at least I hope so, because I saw a right good many of them get burned up and poisoned, and there wasn’t a single one of them that would go see a doctor if they got sick or hurt. That’s why the snake bites bothered me the most. Those copperheads and rattlers could only stand so much, especially with the music pounding like it did and all them folks dancing and hollering and falling out on the floor, kicking over chairs and laying their hands on each other. In all that time, right up until what happened with Christopher, the church hadn’t ever had but one of them die from that carrying on either, at least only one I know about: Miss Molly Jameson, almost eleven years ago. She was seventy-nine when it happened, two years younger than I am now. I think it might’ve been a copperhead that got her. She was standing down front on that little stage when Chambliss lifted it out of the crate, closed his eyes, and prayed over it. He wasn’t more than forty-five years old then, his black hair cut close and sharp like he’d spent time in the army, and he might have for all I knew about him. I don’t think a single one of us knew for sure where he came from, and I figure anyone who said they did had probably been lied to. Once he finished praying over that snake, he handed it to Molly. She took it from him just as gentle as if someone was passing her a newborn baby, this woman who’d never had a child of her own, a widow whose husband had been dead for more than twenty years, his chest crushed up when his tractor rolled over and pinned him upside a tree.

But like I said, she held that copperhead like a baby, and she took her glasses off and looked at it up close like it was a baby too, tears running down her face and her lips moving like she was praying or talking to it in such a soft way that only it could hear her. Everybody around her was too wrapped up in themselves to pay any attention, dancing and carrying on and hollering out words couldn’t nobody understand but themselves. But Chambliss stood there and watched Molly. He held that microphone over his heart with that terrible-looking hand he’d set on fire years before in the basement of Ponder’s feed store. I’d heard that him and some men from the church were meeting for worship down in that basement, drinking lamp oil and handling fire too, and I don’t know just how it happened, but somehow or another Chambliss got his sleeve set on fire and it tore right through his shirt and burned his arm up something awful. They said later that his fingers were even melted together, and he had to pull them apart and set them in splints to keep them separated while they were healing. I didn’t ever see his whole arm because that man didn’t ever roll that right sleeve up, maybe the left one, but not that one. I reckon I can’t blame him. That right hand was just an awful sight, even after it got healed.