Hughes, O., on

letters

Plath’s, S., innate understanding of

reputation as femme fatal

Stevenson, A., on

suicide of

Wevill, D., on

Wevill, David

White, E. B.

The White Goddess (Graves)

Wilde, Oscar

Wilkes, Ashley

“William Wilson”

Williams, William Carlos

Wilson, Don

Winston, Susan Plath

“A Winter’s Tale”

“The Wishing Box”

Wober, Mallory

The Woman and the Work (Butscher)

Women at Yale: Liberating a College Campus (Lever & Schwartz, P.)

Woodrow Wilson fellowship application

Woolf, Virginia

Wooten, William

Wordsworth, William

World War I

World War II

writer’s block

hatred of Plath, A., and

of Hughes, T.

writing. See also poetry

death and

love of

marriage and

schedule

Wunderlich, Ray

Wuthering Heights

Wylie, Elinor

Wylie, Philip

Yaddo

Yale

Yale Younger Poets

Yeats, W. B.

“You Hated Spain”

Young, Nanci A.

“Your Paris”

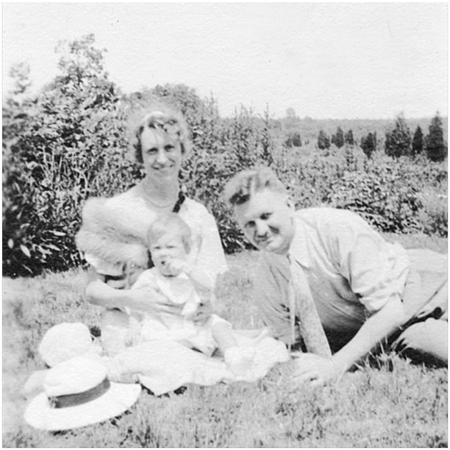

Otto, Aurelia, and Sylvia Plath, July 1933.

Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

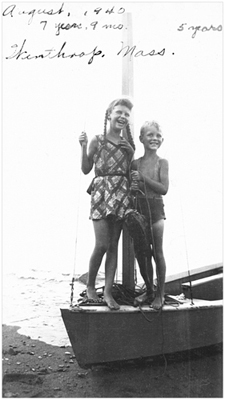

Sylvia and Warren Plath on a sailboat in Winthrop, Massachusetts, August 1940, three months before Otto Plath’s death.

Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

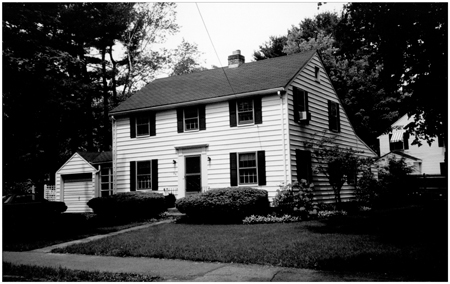

26 Elmwood Road, the home of Aurelia, Warren, and Sylvia Plath, Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

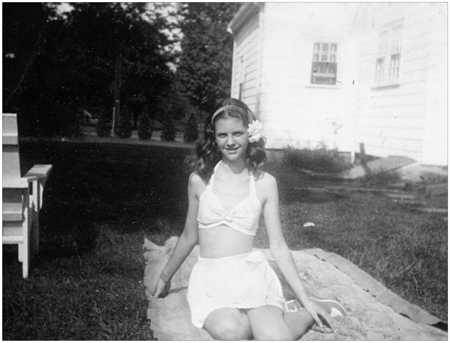

Sylvia Plath sunbathing in the backyard, 26 Elmwood Road, June 1946

Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

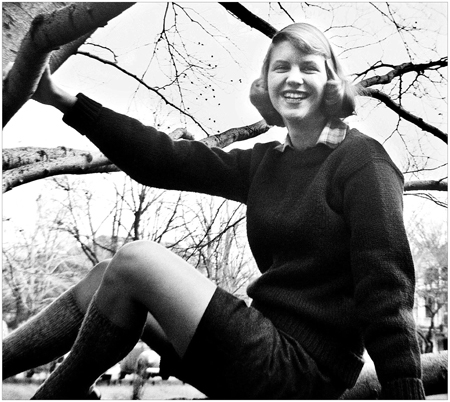

Sylvia Plath, c. November 1954.

Courtesy Judith Denison. Glenda Hydler: Restoration.

Sylvia Plath, April 1954, in front of Lawrence House, Smith College.

Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

The River Cam in Cambridge, where Sylvia studied during her Fulbright years, 1955–57.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

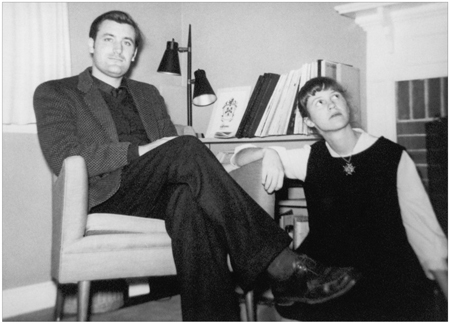

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes in Concord, Massachusetts, December 1959.

Courtesy Marcia Brown and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

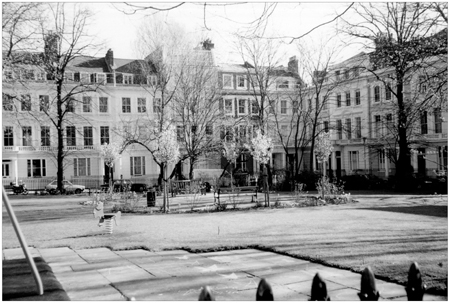

Chalcot Square, London, near the flat where Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes settled after moving from America to England in 1959.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

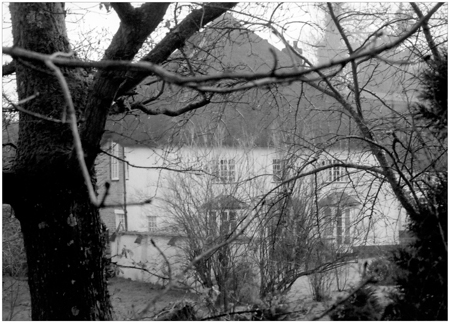

Court Green, Devon, the home Sylvia and Ted Hughes purchased in 1961.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

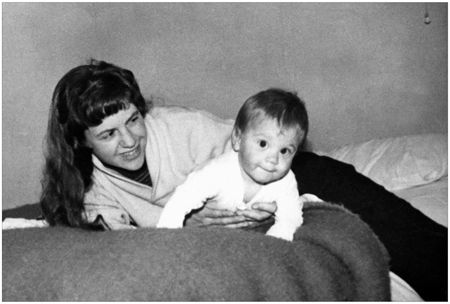

Sylvia and Nicholas Hughes in Devonshire, December 1962.

Photographer unknown. Copyright estate of Aurelia S. Plath. Courtesy Smith College archives.

23 Fitzroy Road, London, the flat where Sylvia died.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

Primrose Hill, near both Chalcot Square and 23 Fitzroy Road, and a favorite of Sylvia’s because of its country air and walkways.

Courtesy Peter K. Steinberg and Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

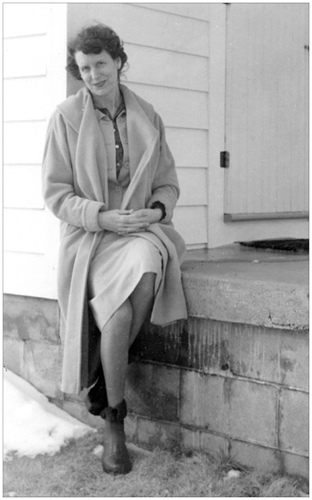

Aurelia Plath, January 1961.

Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

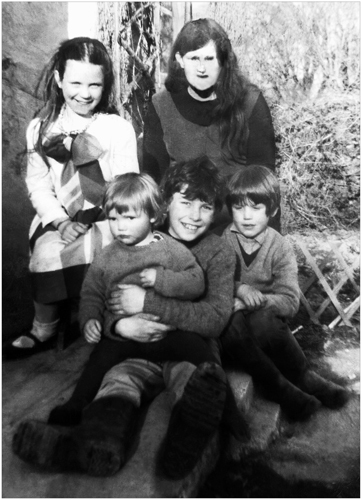

Frieda (top left) and Nicholas (bottom right) with Elizabeth Compton’s children, Hester (top right), Emma (lower left), and James (middle), 1967.

Courtesy Elizabeth Compton Sigmund. Glenda Hydler: Restoration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Without the strong support of my agent, Christina Ward, this biography would not have been written. Without Lindsay Sagnette’s enthusiastic recommendation to her colleagues at St. Martin’s Press, this biography would not have been accepted for publication. Without the enthusiastic backing of my editor, Michael Flamini, this book would not have had such careful encouragement and advice. Without the astute advice of my wife, Lisa Paddock, this book would have lacked a certain polish. Early on, I grew to rely on the expertise, encouragement, and generosity of Peter K. Steinberg, an extraordinary Plath scholar, who pointed me to many important primary sources. He also gave me permission to reproduce his photographs documenting the world of Sylvia Plath. Peter saved me from making several errors. I am very grateful to Susan Plath Winston (Warren Plath’s daughter) for giving me permission to reproduce several photographs and for answering my queries. I am very grateful to Ellis B. Levine of Cowan, Debaets, Abrahams & Sheppard, LLP, for his wise counsel.

Karen V. Kukil, a renowned Plath scholar and archivist, went out of her way to address the needs of my biography. The work she has done at the Smith College archive is stupendous. Owing to its openness and accessibility, the archive’s policies ought to be a model for the world. It is a detriment to scholarship that other repositories of Plath’s papers have surrendered to her estate’s restrictive and censorious protocols. Nevertheless, I appreciate the prompt and generous help I received from Kathleen Shoemaker at Emory University, Helen Melody at the British Library collections of the Ted Hughes and Olwyn Hughes papers, and Beth Alvarez and Ann L. Hudak at the University of Maryland. Less helpful, but still indispensable, of course, is the Plath Collection in the Lilly Library at Indiana University. For expert retrieval of various secondary sources, I am indebted to my wonderful Macaulay Honors College student assistant, Tara Gildea. Her diligent and first-rate work represents what is best about the City University of New York.

David Wevill cordially answered my email queries, but he did not wish to be interviewed. He did agree, however, to my request to reproduce his email reply to one of my queries (see Appendix C). My letters to Marcia Brown and Richard Sassoon went unanswered, but I had the benefit of Constance Blackwell’s memories of her friendship with Sassoon during Sylvia’s time at Smith. What Eddie Cohen had to say seemed bound up in his letters, and that was the story I wanted to tell. W. S. Merwin would vouchsafe almost nothing even to Olwyn Hughes, to whom he replied on 13 October 1987 with the observation that writing about Sylvia “seems to me bad medicine altogether.” I couldn’t see why he would have talked to me, and so I decided not to hazard his rebuff. But I did get an insight into the friendship between Merwin and Hughes in the course of an unexpected, spontaneous conversation with Grace Schulman, my colleague at Baruch College.

Even to this day, most of Olwyn’s friends observe a code of silence. I’m grateful that Marvin Cohen, through the good offices of Charles DeFanti, made an exception for me. For more insight into Olwyn and Ted Hughes, and their treatment of Sylvia Plath, I turned to A. Alvarez, a remarkably generous and welcoming man who patiently went over ground he has eloquently explored in his own writings. I am indebted to him, as well, for discussing his correspondence with Olwyn, now in his papers at the British Library. His wife, Anne, took time during a busy day to discuss with me Olwyn Hughes and Assia Wevill. Similarly, the testimony of Elizabeth Sigmund, married to David Compton when Plath and Hughes resided at Court Green, has been invaluable. Spending nearly two whole days with her, observing her careful recounting of those days in Devon while examining her extensive files, I came away with a greater understanding of why Aurelia Plath believed Elizabeth was essential to Sylvia’s well-being. Rather than just cut up Elizabeth’s memories into the bits and pieces that can be found in previous Plath biographies, I thought it fitting to let her speak in her own voice (see Appendix D) as a means of conjuring a bygone era. To Elizabeth’s husband, William Sigmund, who occasionally joined our conversations and provided delicious lunches and teas—not to mention transportation—I want to express my gratitude and affection.