But across more than 3,000 years of history, Jerusalem had become immutably entwined with two other world religions: Judaism and Islam. These faiths also treasured the city, reserving particular reverence for the area known either as the Temple Mount, or Haram as-Sharif, a raised enclosure in its eastern reaches, containing the Dome of the Rock and the Aqsa mosque, and abutted by the Wailing Wall. To Muslims this was the city from which Muhammad made his ascent to heaven, the third-holiest site in the Islamic world. But it was also the seat of the Israelites, where Abraham offered to sacrifice his son and the two Temples were built.

Just as it is today, Jerusalem became a focus of conflict in the Middle Ages precisely because of its unrivalled sanctity. The fact that it held critical devotional significance for the adherents of three different religions, each of whom believed that they had inalienable and historic rights to the city, meant that it was almost predestined to be the scene of war.

The task ahead

The First Crusade now faced a seemingly insurmountable task–the conquest of one of the known world’s most fearsomely fortified cities. Even today, amid the urban sprawl of modern expansion, Jerusalem is able to convey the grandeur of its past, for at its centre lies the ‘Old City’, ringed by Ottoman walls closely resembling those that stood in the eleventh century. If one looks from the Mount of Olives in the east, stripping away the clutter and bustle of the twenty-first century, the great metropolis that confronted the Franks in 1099 comes into focus.

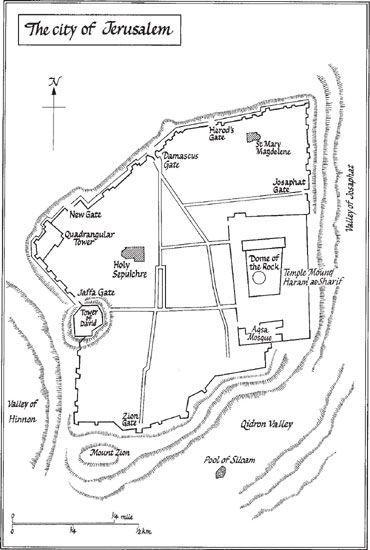

The city stood isolated, amid the Judean Hills, on a section of raised ground, with deep valleys falling away to the east, south-east and west, enclosed within an awesome two-and-a-half-mile circuit of battlements, sixty feet high and ten feet thick. Realistically, the city could only be attacked from the flatter ground to the north and south-west, but here the walls were reinforced by a secondary curtain wall and a series of dry moats. Five major gates, each guarded by a pair of towers, pierced this roughly rectangular system of defences. Jerusalem also possessed two major strongholds. In the north-western corner stood the formidable ‘Quadrangular Tower’, while midway along the western wall rose the Tower of David. One Latin chronicler described how this dread citadel was ‘constructed of large square stones sealed with molten lead’, noting that if ‘well supplied with rations for soldiers, fifteen or twenty men could defend it from every attack’.35

As soon as the crusaders arrived at Jerusalem a worrying rift within their ranks became apparent, as their armies divided in two. Since the siege of Arqa, Raymond of Toulouse’s popularity had been in decline and, now, abandoned by Robert of Normandy, the count was left struggling even to retain the allegiance of the southern French. Raymond positioned his remaining forces on Mount Zion, south-west of the city, to threaten the southern Zion Gate. The campaign’s emerging leader, Godfrey of Bouillon, meanwhile moved to besiege the city from the north, between the Quadrangular Tower and Damascus Gate. Enjoying the support of Arnulf of Chocques, the priest who had helped to discredit the Holy Lance, Godfrey was joined by the two Roberts and Tancred. In strategic terms, the division of troops had some merit, exposing Jerusalem to attack on two fronts, but it was also the product of gnawing discord.

This was all the more troubling because the Franks could not pursue a long-drawn-out encirclement siege at Jerusalem, as they had at Antioch. The vast length of the city’s perimeter wall meant that, with limited manpower at their disposal, enforcing an effective blockade would be impossible. More pressing still was the issue of time. The crusaders had taken an enormous, if arguably necessary, gamble by marching at speed from Lebanon, without pausing to secure their rear or to establish any reliable network of supply. They were now hundreds of miles from their nearest allies, all but cut off from reinforcement, logistical support or the possibility of escape. And all the while they knew that al-Afdal was racing to prepare his Fatimid forces, bent upon relieving the Holy City and stamping out the Christian invasion. The near-suicidal audacity of the Latin advance left them with but one option: crack the shell of Jerusalem’s defences and fight their way into the city before the Egyptian army arrived.

The City of Jerusalem

In this final, fraught stage of their expedition, the Franks could muster around 15,000 battle-hardened warriors, including some 1,300 knights, but this army was largely bereft of the material resources needed to prosecute an assault siege. The overall size of the garrison they faced is unknown, but it must have numbered in the thousands and certainly contained an elite core of at least 400 Egyptian cavalrymen. Jerusalem’s Fatimid governor, Iftikhar ad-Daulah, meanwhile, had been quite assiduous in preparing to face an offensive, laying waste to the surrounding region by poisoning wells and felling trees, and expelling many of the city’s eastern Christian inhabitants to prevent betrayal from within. When the crusaders launched their first direct assault on 13 June, just six days after their arrival, the Muslim defenders offered staunch resistance. At this stage the Franks possessed only one scaling ladder, a pitiful arsenal, but desperation and the prophetic urgings of a hermit encountered wandering on the Mount of Olives persuaded them to chance an attack. In fact, Tancred spearheaded a fierce strike on the ramparts in the city’s north-western quadrant that almost achieved a breach. Having successfully raised their sole ladder, Latin troops sped upwards, seeking to mount the walls, but the first man to grab the parapet promptly had his hand chopped off by a mighty Muslim sword stroke and the onslaught foundered.

In the wake of this dispiriting reversal the Frankish princes reconsidered their strategy, electing to postpone any further offensive until the appropriate weapons of war could be constructed. As a frantic search for materials began, the crusaders started to feel the effects of the baking Palestinian summer. For the time being at least, food was not the main cause of concern, as grain had been brought from Ramla. Instead, it was water shortages that began to weaken Latin resolve. With all the nearby watering holes polluted, the Christians were forced to scour the surrounding region in search of drinkable liquid. One Frank recalled rather forlornly: ‘The situation was so bad that when anyone brought foul water to camp in vessels, he was able to get any price that he cared to ask, and if anyone cared to get clear water, for five or six pennies he could not obtain enough to satisfy his thirst for a single day. Wine, moreover, was never, or very rarely, even mentioned.’ At one point some of the poor died after gulping down filthy marsh water contaminated with leeches.36

Luckily for the crusaders, just as these shortages were beginning to take hold help arrived from a seemingly unheralded quarter. In mid-June a six-ship-strong Genoese fleet made anchor at Jaffa, a small natural harbour on the Mediterranean coast that was Jerusalem’s nearest port. Their crew, which included a number of skilled craftsmen, made their way to join the siege of the Holy City, laden with an array of equipment, including ‘ropes, hammers, nails, axes, mattocks and hatchets’. At the same time, the Frankish princes used intelligence garnered from local Christians to locate a number of nearby forests and soon began ferrying in timber by the camel-load. These two developments transformed Latin prospects, putting them in a position to build siege machinery. For the next three weeks they threw themselves into a furious programme of construction, fashioning siege towers, catapults, battering rams and ladders, almost without pause, but always with one eye upon the impending arrival of al-Afdal’s relief army. Meanwhile, inside Jerusalem, Iftikhar ad-Daulah looked to the arrival of his master, even as he oversaw the assembly of scores of his own stone-throwing devices and the further strengthening of the city’s walls and towers.