The only way to get an accurate recording of the sounds the dogs would experience during their scans would be to program the actual scan sequence with the exact parameters necessary to scan the dogs’ brains. But since nobody had scanned a dog’s brain before, at least not with fMRI, we had no idea what the correct settings might be. With a dog in the scanner, we could figure out the correct settings, but we needed the right settings in order to record the sounds to train him to get him into the scanner in the first place.

I felt like a dog chasing his tail.

At lab meeting, I brought up the conundrum.

“What if you use the standard human settings to record the scanner noise?” Lisa suggested.

“It might be good enough,” I said. “But what if it isn’t?”

“I bet the dogs could tell the difference,” Andrew said. “If we train them with the wrong sounds, they might freak out when they hear the real thing.”

“We need a stand-in,” I said. “Something that can take the place of the dog while we fiddle with the scanner settings.”

Lisa’s forehead knitted up in thought. Everyone else looked at the floor. Before anyone suggested it, I headed off the obvious.

“We’re not using a dead dog.”

“Why don’t you just go to the supermarket and buy a steak and scan that?” Gavin joked.

“You mean like the famous dead-salmon study?” Andrew asked.

A few years before, neuroscientists had used fMRI to scan a salmon purchased at a local fish market. As they wrote in their findings, the fish “was not alive at the time of scanning.” They presented their results at a conference, but most scientists dismissed it as a joke. It wasn’t. The point was to measure the accuracy of fMRI and how the technique could sometimes lead to the appearance of brain activations that weren’t actually there. Obviously a dead salmon couldn’t have brain activation, but the scientists showed that with poor statistical technique, it might appear that way.

Gavin’s joke wasn’t half bad. But a steak (or a salmon) would be a lousy stand-in for a dog.

“We need something more doglike,” I said.

“A pig?” Gavin said.

“Too big.”

“How about a lamb?” Andrew suggested.

“Can you buy a whole lamb at the market?” I wondered.

After a few phone calls to some local butchers, Andrew found a lead. It wasn’t a whole lamb—you needed to get that directly from a farm—but there was a market that might sell us a lamb’s head.

“I think he said they get their delivery of lamb heads on Wednesdays,” Andrew explained. “I’m not completely sure because I couldn’t understand some of what he was saying. But he definitely said they go fast.”

“Today is Wednesday,” I pointed out.

“Giddyup!”

The halal meat market had no sign. The “market” consisted of a counter at the rear of a convenience store, itself sandwiched in a rundown strip mall and sharing a wall with a video store specializing in bootlegged Middle Eastern movies.

Andrew and I walked in to find a trio of bearded men hanging out at the cash register, smoking cigarettes and watching soccer on TV. They said nothing as we made our way to the rear of the store. I noticed some elaborate water pipes on display.

At the butcher’s counter, a spread of organ meats glistened beneath the glass case. Kidneys I recognized. The rest—not so much. The animals of origin were a mystery to me too.

A squat guy wearing a tight soccer jersey peered over the counter.

“You guy call about lamb head?” he asked in a Middle Eastern accent.

“Yes.”

“How many you want?”

Andrew and I looked at each other.

“How many do you have?” I replied.

“Lots.”

We conferred briefly and decided that we should have a backup in case something went wrong.

“Two,” I said.

The butcher disappeared through a doorway covered with vinyl slats. A moment later he returned and deposited two heads on the counter with an authoritative clank.

“They’re frozen,” I said.

“Yes,” said the butcher, “fresh frozen.”

They bore a resemblance to a lamb, but as all the wool had been removed, it was hard to tell what they were. The lips had retracted a bit, and the faces were fixed in permanent grimaces.

The size was right, I had to admit. In fact, they were about the same size as Lyra’s head. I shivered and pushed that unpleasant image out of my mind.

“Where is the rest of the lamb?” I asked.

“Just head,” he replied.

“Do they still have their brains?”

The butcher brought his fingers to his mouth in the sign known to foodies around the world and said, “Yes. Delicacy.”

Ideally, we would have gotten a whole lamb to stand in for a dog. Anything you put inside an MRI disturbs the magnetic field. The bigger the object, the greater the disturbance, and as the scanner compensates for these disturbances, it makes different kinds of sounds. The lamb’s head was not going to have enough mass to replicate the disturbance created by a dog. We needed something else.

Andrew pointed to a pair of hooves in the butcher’s case. They appeared to be the front legs of a calf starting just above the ankle joint.

In the actual MRI, the dogs would be scanned in a sphinx position. Their heads would be upright, supported by a chin rest, and their front paws would be sticking straight forward. Andrew realized we could use the calf hooves to simulate the front paws of the dog. The combination would give a close approximation to the shape and mass of the part of the dog that would be at the center of the scanner. We paid for our meats and headed back to the lab with two lamb heads and a pair of calf hooves.

The vegetarians in the lab weren’t going to be happy.

We let the heads thaw overnight and reserved time on the MRI scanner for the following evening. Scanning dead animal parts in the MRI is the kind of thing best done discreetly. Once thawed, the heads, now swimming in their own juices, looked even worse. Their eyes had taken on an opaque haze. Andrew and I double-bagged everything and headed to the scanner.

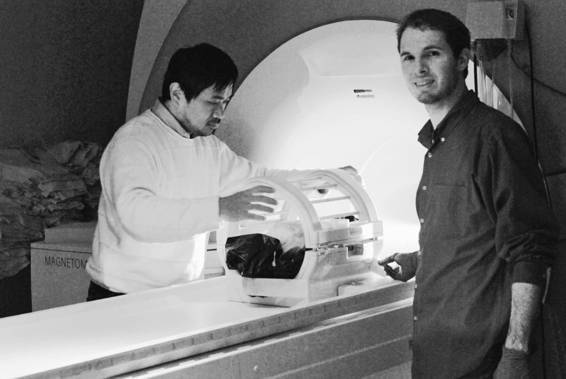

We were greeted by Lei Zhou, a Chinese postdoc on duty that evening. Lei had received his PhD in physics and was intimately familiar with the technical wizardry behind MRI. His English, however, had a ways to go. I could only hope that we understood each other during this unusual procedure.

Lei and Andrew preparing to scan the lamb’s head.

(Gregory Berns)

Andrew unloaded our cargo, and we proceeded to arrange it in the head coil of the scanner. With foam pads propping up the body parts, Lei snapped on the top of the coil and sent the whole mess into the center of the scanner.

When you place something in the MRI, the magnetic field tugs on the atoms inside the object. In living tissue or, as in the case of the lamb’s head, formerly living tissue, hydrogen is the most common atom. There are two hydrogen atoms in every water molecule, and water accounts for 60 percent of body weight in humans. Hydrogen is also abundant in the brain. The outer membranes of neurons and their supporting cells, called glia, are rich in fat and cholesterol, which have large numbers of hydrogen atoms.

A hydrogen atom has one proton and one electron. The proton is like a spinning top. Normally, the protons spin in random directions, but inside the MRI they line up with the magnetic field. Like spinning tops, the protons also wobble a little bit. The stronger the magnetic field, the faster they wobble. If you hit the protons with radio waves exactly in sync with their wobbling, the protons jump into a higher energy state. This is called magnetic resonance. Different types of atoms resonate at different frequencies. For the strength of scanner we use, hydrogen resonates at 127 MHz, which falls in the range of radio waves—just beyond the FM dial. Carbon, another common element in the body, resonates at 32 MHz. MRI works by sending in a blast of radio waves that excite the atom of interest—in most cases hydrogen because of its abundance and superior sensitivity to magnetic fields. When the radio waves are turned off, the protons relax back to their original state and, in the process, cause an oscillating magnetic field that can be picked up by an antenna. The head coil is nothing more than a fancy FM radio antenna that picks up these signals from the protons in the brain.