To his amazement, the crowd gave him a standing ovation. Most of them probably didn’t change their minds about the open-housing bill, but they did change their minds about their Congressman. They recognized that he had courage and that he was honest. In the fall of 1968, seven months after the open-housing vote, George Bush ran for reelection unopposed.

I followed the open-housing debate, and I was very proud of my father. I admired the way that he took a principled position, defended his decision, and stood up to the political mob—all while maintaining his dignity. The lesson of his vote on the open-housing bill is that although citizens might not agree with the decision you make, they appreciate a leader who is willing to make a tough decision. George Bush did that throughout his career. I kept his example in mind when I faced tough decisions of my own, such as ordering the troop surge in Iraq or approving major government intervention in the marketplace to prevent a meltdown during the financial crisis.

—

IN THE PRESIDENTIAL race of 1968, Richard Nixon defeated Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who had stepped forward to run when LBJ shocked the country by declining to seek reelection. Nixon carried thirty-two states and more than three hundred electoral votes. He took his oath of office on January 20, 1969. An hour later, LBJ departed the nation’s capital, where he had been a fixture since his election to Congress in 1937. He left with few friends.

Out of both respect and sympathy, Dad decided to go to Andrews Air Force Base to see off the former President. Amid the large crowd, a few other Congressmen showed up, including LBJ’s longtime friend Jake Pickle, but Dad was the only Republican. When Lady Bird Johnson’s press secretary, Liz Carpenter, noticed Dad standing in the crowd, she pointed him out to the outgoing President. LBJ walked over, shook his hand, and said, “George, I’m grateful that you’re here. Come visit me and Lady Bird at the ranch sometime.”

A few months later, Dad accepted the offer. LBJ drove him around the sprawling grounds of his ranch in Johnson City, Texas. At lunch, Dad asked him a question: Should he leave his safe seat in the House to run for the Senate against Ralph Yarborough in 1970? The former President, who had served in both the Senate and the House, replied in classic LBJ style.

“George,” he drawled, “the difference between the Senate and the House is the difference between chicken salad and chicken shit.”

While he didn’t put it quite so colorfully, President Nixon agreed that Dad should run. He promised to help with the campaign and assured Dad a soft landing if he didn’t win the race.

Not everyone thought that Dad should run. Many in his district urged him to keep his coveted seat on the House Ways and Means Committee. Once again, however, George Bush decided to take a risk. In January 1970, he announced that he would leave his safe seat in the House to run for the Senate. While many factors played a role in Dad’s decision, I’ve always suspected that part of the reason was that he wanted to serve in the same body in which his father, Senator Prescott Bush, had served.

By the time Dad launched his 1970 Senate campaign, I had finished my pilot training and was flying planes with the Texas Air National Guard in Houston. I had time between training sessions to help out with the campaign. I traveled across the state with him on his kickoff tour. This time I was very optimistic, and so was Dad. The state’s demographics were changing, Dad had built a good reputation, and Senator Yarborough was increasingly out of step with most Texans.

On the day my father cruised to victory in the Republican primary, the dynamics of the race changed dramatically. I remember riding with Mother, Dad, and some of his campaign aides when a radio broadcaster announced that Lloyd Bentsen had defeated Ralph Yarborough in the Democratic primary. That was not good news. Bentsen was a decorated World War II pilot, a former House member from South Texas, and a successful business executive in Houston. Like my father, Bentsen was a young, charismatic candidate who had run hard to the right of Yarborough. The philosophical distinctions in the race had just been erased, and Bentsen would benefit from a huge advantage in voter registration. Dad suddenly faced an uphill battle. The car fell silent for a few seconds. Then my father tried to reassure us. “It’s okay,” he said. “We can still win this thing.”

Two factors ultimately doomed Dad in the race. First, Bentsen was able to appeal to Texans’ longtime political heritage with his effective slogan “Texas needs a Democratic Senator.” (The other Senator at the time was John Tower, a Republican.) Second, the Texas legislature had placed a constitutional amendment on the ballot that would allow each county to vote on whether to approve the sale of liquor by the drink. The measure drew heavy opposition from rural Texans in dry counties, who derided the amendment as an “open saloon” law. As a result, rural turnout was high—and in those days rural Texans voted overwhelmingly Democratic. I remember going to rural Kaufman County in 1970 to shake a few hands on Dad’s behalf. When I arrived at the county courthouse, the building was nearly vacant. I asked where everybody had gone. One of the few people left said, “They heard a Republican was coming.” (In a sign of the changes in Texas politics, I received a warm greeting when I returned to the Kaufman County courthouse as a Republican candidate for Governor in 1994. On Election Day, I carried the county.)

Thanks to Bentsen’s strength as a candidate and the rural Democratic turnout, he defeated Dad 53 percent to 47 percent. This loss hurt a lot more than 1964. That one could be explained away by the Johnson landslide. This one seemed like the death knell for George Bush’s political career.

Dad was gracious in defeat. He thanked everybody that he could find. He returned to Washington for the conclusion of his congressional term—likely the final months of his career in elected office. He was not bitter. He held no grudges. He accepted the voters’ decision and prepared to move on with his life. Then one day he got a phone call from the President. Richard Nixon wanted to see him at the White House. From the despair of a second defeat, a career-changing opportunity arose.

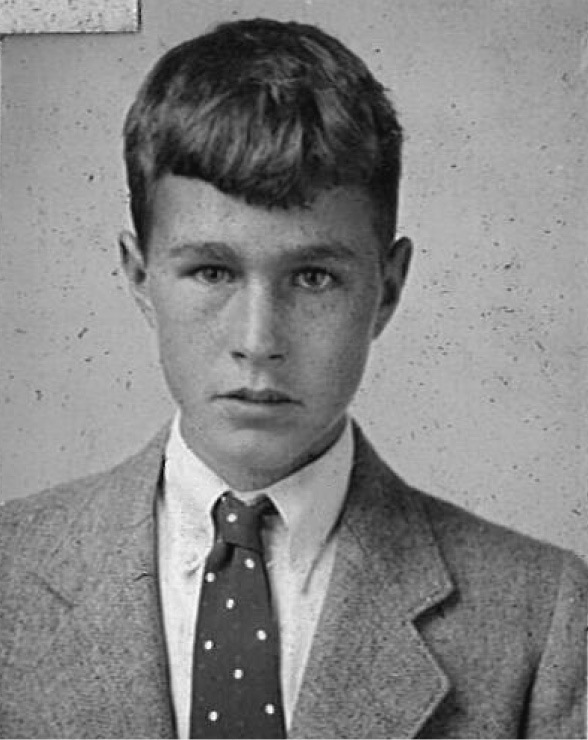

Even as a young man at Phillips Academy, George Bush displayed a natural leadership ability. People have always gravitated toward him and wanted to follow him. George Bush Presidential Library and Museum (GBPLM)

George Bush enlisted on his eighteenth birthday and became the youngest pilot in the Navy. His plane was shot down over the Pacific on September 2, 1944. GBPLM

Lieutenant George Bush married Barbara Pierce on January 6, 1945, while on leave from the Navy. Dad says the engagement ring is a star sapphire; Mother still suspects it might be blue glass. GBPLM

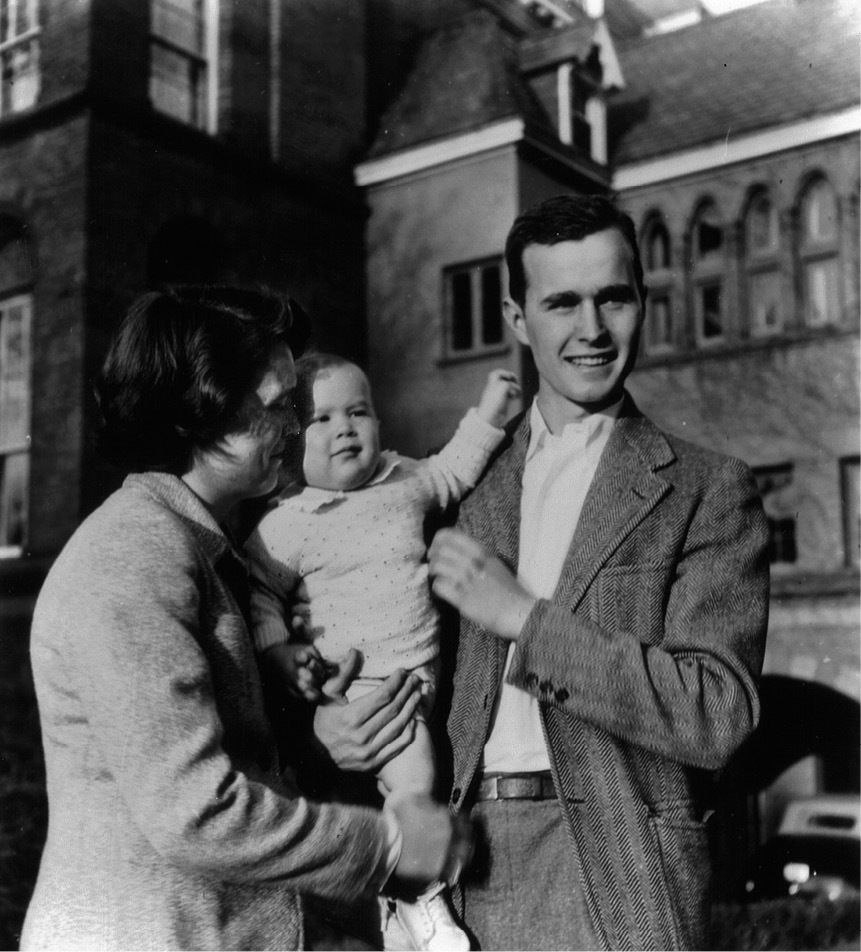

I was born on July 6, 1946, while Dad was a student at Yale. It’s hard to imagine how he did it all—top student, star athlete, loyal friend, and devoted husband and father. As Mother put it with characteristic bluntness, “He worked hard.” GBPLM

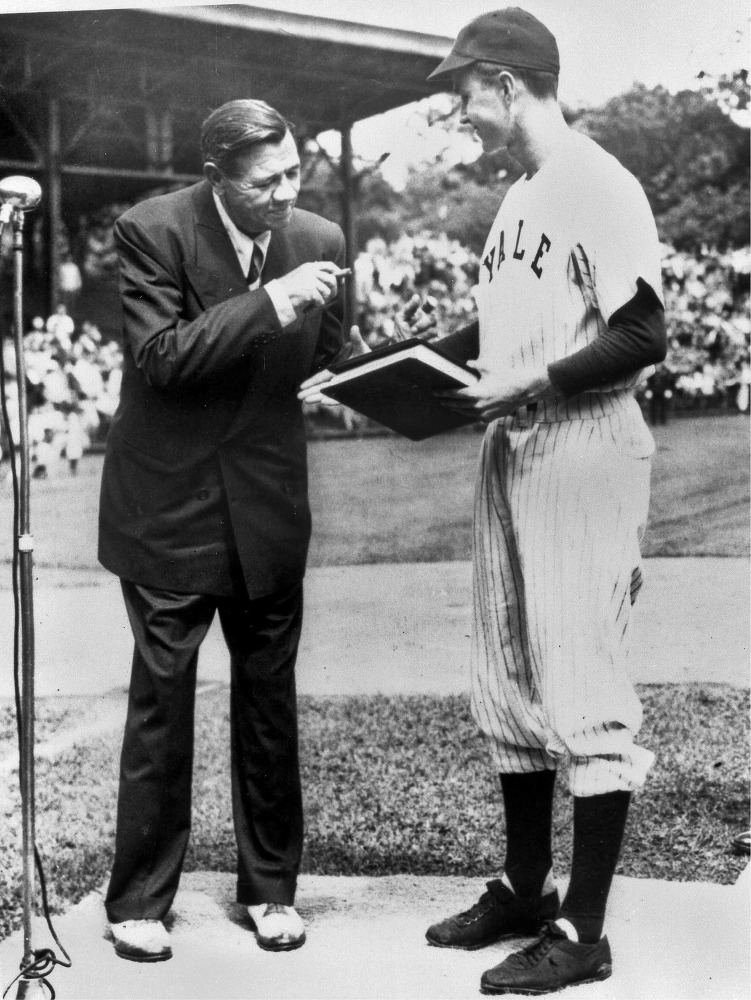

As Captain of the Yale baseball team, Dad met Babe Ruth during his senior year. The photo became iconic: one great man near the end of his life, another embarking on his. GBPLM

Family has always come first to Dad. Walker’s Point, our family home in Kennebunkport, Maine, is a close second. Here we are celebrating the Silver Anniversary of Prescott and Dorothy Bush in 1947. GBPLM