* * *

A devastated Beatrice Patton flew home to America the day after her husband’s funeral. It was Christmas, but she had given herself over to grief and mourning. There would be no holiday for her.

In their thirty-five years together, she and George Patton endured countless separations as he waged war in Mexico, Africa, France, and Germany. In the letters he wrote during these long times away from her, she came to know his innermost thoughts and his deep love. George Patton had dyslexia, which makes spelling, reading, and writing a chore, so the very act of writing was as much a symbol of his love as the words themselves.

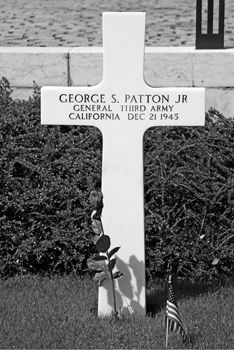

But there would be no more letters from George Patton. As his body was lowered into the cold, wet ground of Luxembourg, Beatrice Patton’s grief was almost overwhelming.

Patton’s grave

Her beloved Georgie was no more.

Beatrice Patton never remarried. Her grandson James Patton Totten, speaking in 2008, admitted that she hired several private detectives to look into her husband’s death. Each of these investigations was unsuccessful in finding any hard evidence of an assassination.

A lifelong equestrienne, Beatrice suffered a ruptured aortic aneurysm while galloping across a field outside Hamilton, Massachusetts, eight years after her husband’s death. Though Mrs. Patton immediately fell from the horse, she was dead before hitting the ground. As noted earlier, she had long made it clear that she wished to be buried with her husband. When the U.S. Army refused to allow her to be interred at the American Military Cemetery in Luxembourg, her children smuggled her ashes to Europe and sprinkled them atop the grave of George Patton.

* * *

The hospital where Patton died remained a U.S. Army installation until July 1, 2013. At that time, the 130th Station Hospital, or Nachrichten Kaserne as it later became known, was closed and handed over to the German government. With the exception of a small ceremonial plaque that was hung outside the door, Room 110 was not treated with any fanfare after Patton’s death, and was long used as a radiology lab. In the course of researching this book, a visit was paid to the facility to see this very special room. The place where Patton died was quite ordinary. Coincidentally, this visit occurred just hours before the decommissioning, making Martin Dugard the last American visitor to enter Patton’s hospital room before it was handed over to the Germans.

* * *

PFC Horace Woodring, driver of Patton’s Cadillac at the time of the accident, returned home to Kentucky after the war. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower took the time to assure him personally that he had not been at fault in the auto accident that paralyzed the general. Nevertheless, Woodring was devastated by Patton’s death. “I felt like a kid who had lost his father,” he later remembered, “because that’s how I felt about him. I had every admiration in the world for the man. I just thought he was the greatest.” When Woodring’s wife gave birth to a son, they gave him the middle name of Patton. Woodring and his family moved to Michigan in 1963, where he sold cars and rode snowmobiles to indulge his penchant for speed. Woodring died of heart disease in a Detroit hospital in November 2003. He was seventy-seven years old. Until the day he died, Woodring asserted that the accident that killed Patton was inexplicable.

* * *

The hero of the Battle of Fort Driant, Pvt. Robert W. Holmlund, who won the Distinguished Service Cross, was promoted posthumously to staff sergeant. Strangely, he has become a historical mystery. Staff Sergeant Holmlund is not listed as being buried in any of the American military cemeteries in Europe; nor is he buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

* * *

Capt. Jack Gerrie was sent home to Wisconsin for a thirty-day leave after the battle for Fort Driant. On his way back into Europe, he passed through a depot, to await transportation to his unit. While there, on December 29, 1944, Gerrie was killed when a captured German gun he was examining fired into his head.

* * *

German generals Ernst Maisel and Wilhelm Emanuel Burgdorf, who came to Erwin Rommel’s home bearing the field marshal’s fatal suicide pill, lived two very different lives after that day. Maisel was promoted to lieutenant general (Generalleutnant) in the waning days of the war and placed in command of the Sixty-Eighth Infantry Division. He was captured by American forces on May 7, 1945, released two years later, and lived out his days in the mountains of German Bavaria, where he died on December 16, 1978, at the age of eighty-two.

Burgdorf was long dead by then. In fact, he had committed suicide five days before Maisel was taken prisoner. Called to Adolf Hitler’s Berlin bunker during the final days of the war, Burgdorf witnessed the Führer’s signing of his last will and testament. Three days later, Burgdorf shot himself in the head rather than be captured by Soviet troops.

* * *

Just prior to Burgdorf’s suicide, fellow bunker residents Joseph and Magda Goebbels chose a most grisly death. On May 1, 1945, Magda Goebbels medicated her six children with a drink containing morphine. She then cracked a vial of cyanide into their mouths as they slept, killing them one by one. She and her husband later went up out of the bunker, where she bit into a cyanide pill and Joseph Goebbels fired a bullet into the back of her head. Goebbels then killed himself with a pill and a simultaneous gunshot.

The other elite members of the Nazi Party died in similar fashion. SS leader Heinrich Himmler, who was captured by the British three weeks after fleeing Berlin, killed himself in prison with a hidden cyanide pill. Hermann Goering, the corpulent head of the Luftwaffe, was arrested by American troops on May 6, 1945. On September 30, 1946, he was sentenced to be hanged by the neck until dead. But Goering, who openly laughed and joked during the Nuremberg Trials, and declared that gruesome films showing Nazi concentration camp atrocities were faked, did not want to die a public death. With the unwitting help of Herbert Lee Stivers, a nineteen-year-old American army guard, a cyanide ampoule was smuggled into Goering’s cell and he committed suicide. A local German girl who had caught Stivers’s eye while he was off duty convinced him to carry “medicine” to Goering hidden inside a pen. Afterward, Stivers never saw the girl again. “I guess she used me,” he lamented when Stivers finally admitted what had happened. He did so in 2005, sixty years after the fact, explaining that he was still bothered by a guilty conscience.

Goering’s body was put on public display in Nuremberg before being cremated.

* * *

Manfred Rommel, son of Erwin Rommel, returned to his post as a Luftwaffe antiaircraft gunner shortly after his father’s forced suicide. He soon deserted and surrendered to French forces. After his release from captivity, he went to college and then entered politics, where he became mayor of Stuttgart and a leading liberal voice in postwar Germany. Magnanimous and much admired, he refused to run for national office, despite the widespread belief that he could have risen to chancellor. Rommel formed friendships with the sons of Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery and George S. Patton. He died on November 7, 2013, at the age of eighty-four.

* * *

Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower returned home a hero. He did not believe that a military officer should interest himself in politics. So despite widespread popular support for an Eisenhower presidential candidacy in 1948, he accepted a position as head of Columbia University, in New York City, rather than running for office. However, he soon changed his mind. He was elected president of the United States in 1952 and 1956, serving two terms. When doctors told him that his chain-smoking was a hazard to his health, Eisenhower quit the four-pack-a-day habit cold turkey. He died of heart failure on March 28, 1969. He was seventy-eight years old.