Yet Oppenheimer also realized that this device brought an entirely new form of evil to mankind. “I am become Death,” he thought to himself, “the destroyer of worlds.”2

Truman had been waiting for confirmation of the blast results, and received them while on his way to Potsdam. The coded message detailing the bomb’s success was handed to him upon his arrival: “Operated this morning. Diagnosis seems satisfactory, and already exceeds expectations,” it read. With those words, Truman instantly has the power to assert American demands at the Potsdam Conference. No fighting force on earth possesses such a weapon, and he can threaten to use it on whoever stands in America’s way. Here at Potsdam, Truman uses the bomb as leverage to gain assurances that the Russians will join the war against the Japanese. The president also opposes Russian demands that the German people pay for the rebuilding of postwar Europe, with the bulk of those reparations going directly to the Soviet Union.

Yet Stalin is not afraid. Unbeknownst to Truman, he knows all about the atomic bomb, thanks to his extensive global intelligence network.3 He has deliberately prepared for this moment, determined not to give away any hint of emotion that will reveal the depth of Russian espionage in America.

It does not matter that America is an ally. The Russians spy on anyone who is a threat, considering no act of intrigue to be off limits. Stalin believes that “atomic bombs are meant to frighten those with weak nerves.” Besides, his scientists are hard at work on an atomic bomb of their own. In four short years, the Russians will detonate a giant fireball.

Simply put, Joseph Stalin is determined to rule the world.

No American president, or American general, will stand in his way.

* * *

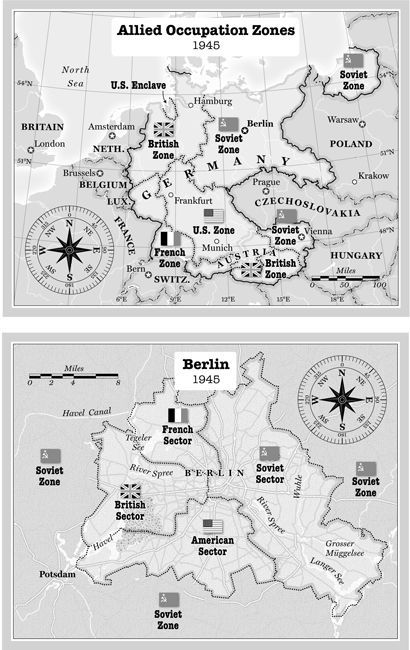

The outcome of the Potsdam Conference is harsh: in keeping with an earlier agreement at Yalta, Germany will be divided into occupation zones governed by the Allies. Truman also secures a firm commitment from Stalin to join the war against Japan. But after meeting Stalin in person, Truman realizes that the dictator is not the friend to America that FDR believed him to be. Thus begins Truman’s policy of taking a hard line against the Russians, and the start of the Cold War that George S. Patton has long predicted.

* * *

The sun shines brightly over Germany as George Patton stands at attention. The fingertips of his right hand are firmly pressed to his polished helmet in salute. Dwight Eisenhower stands to his right, also saluting the American flag as it is raised over Berlin for the first time. President Harry Truman stands to Patton’s left with his hand over his heart. Next to him stands Gen. Omar Bradley.

Per a 1944 agreement between the Allies known as the London Protocol, Berlin is now the territory of the four occupying powers: the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and France. Each nation governs a portion of the city. Russia still controls the areas of Germany surrounding the city, making Berlin a rubble-filled island. “You who have not seen it,” Patton said of the German capital, “do not know what hell looks like.”

General Eisenhower, General Patton, and President Truman at the Berlin flag-raising ceremony

Patton was invited to Potsdam as a visitor to the conference, and from there traveled by car with the president and his fellow generals to Berlin for the flag raising ceremony. He has grown despondent in the past few months, undone by the fact that his fighting days are over. He plays squash and rides horses in the Bavarian countryside to keep himself in shape, and has even tried giving up cigars, but to no avail. By all outer appearances, he looks fit and healthy. But the reality is that he is bored, spending his days attending ceremonies, reviewing troops, saluting the flag, and pinning medals on those whose wartime commendations have finally come through. Without a war to fight, Patton is lost.

To make matters worse, the new president dislikes Patton. Back in 1918 the two men fought in the great Battle of Meuse-Argonne, and Patton surely appreciated the precision artillery support provided by Truman’s Battery D, even though he didn’t know Truman personally. A colonel in those waning days of World War I, he outranked Captain Truman, but now the tables are turned.

“Don’t see how a country can produce such men as Robert E. Lee, John J. Pershing, Eisenhower, and Bradley,” Truman will write in his journal, “and at the same time produce Custers, Pattons and MacArthurs.”

Truman’s scathing opinion of the general is based solely on a first impression. He has not taken the time to get to know Patton, and the two will never engage in a meaningful discussion of any kind.

Truman just doesn’t like him.

The two men are polar opposites.

Patton has swagger; Truman is humble.

Patton is tall and athletic, a larger-than-life military hero. The diminutive, bespectacled Truman, on the other hand, looks like the bank clerk he once was.

Patton was born into wealth, and then married into even more money. Truman has been handed nothing in his life—nothing, that is, except the presidency.

In Patton, Truman sees a braggart who struts around like a peacock in his showy uniform, with the polished helmet and bloused riding pants.

Truman dresses simply, and avoids putting on airs. He detests Patton’s flashy style. Despite the many pressing international obligations on his mind as the flag is being raised over Berlin, Truman takes time to covertly count the number of stars adorning Patton’s uniform—and is appalled to find them adding up to twenty-eight.

With the Second World War now at an end, the president has little need for a general who believes it his birthright to speak his mind, especially when it creates international discord.

The official American policy toward the Germans is that anyone previously connected with Nazi Germany is ineligible to help the nation rebuild. The Russians agree; in fact, this is a cornerstone of the Potsdam discussions. But Patton dissents. He speaks fearlessly about the lunacy of “denazification,” telling the press that it is “no more possible for a man to be a civil servant in Germany and not have paid lip service to Nazism than it is for a man to be a postmaster in America and not have paid at least lip service to the Democratic Party or the Republican Party when it is in power.”

Patton disagrees with official American policy. One disturbing element of which is that former German soldiers be used as forced labor in Russia, France, and the United Kingdom. These men, Patton feels, should be used to rebuild their own country. Germany’s hospitals are no longer functional, its sewer systems don’t work, the roads and bridges have been bombed, and there are millions of former POWs and displaced persons who will need shelter and food once winter comes.

So with words that put him directly at odds with the policies of his president, Patton tells a reporter that German labor is the solution to rebuilding Germany—whether or not someone was once a Nazi. He says, “My soldiers are fighting men and if I dismiss the sewer cleaners and the clerks[,] my soldiers will have to take over those jobs. They’d have to run the telephone exchanges, the power facilities, the street cars, and that’s not what soldiers are for.”

In his own way, Patton is still fighting battles. Even as he quietly begins making plans to leave the military, he wages an ironic war in favor of the German people. “The Germans are the only decent people left in Europe. It’s a choice between them and the Russians. I prefer the Germans.”4

The Russians interpret this stance as an attempt to shield former SS members, perhaps to use them against the Russians in a future war. They have lodged a formal complaint with Omar Bradley suggesting just that, noting that Waffen SS fighters who surrendered to the Third Army in Czechoslovakia during the month of May have not shown up on the lists of individuals turned over to the Russians for repatriation. Soviet spies now fill Bavaria, hunting these men down.