“Nuts,” he mutters, still half asleep.

Jones soon arrives with the note. There are two, actually: one typed in German and the other in English.

“They want to surrender?” McAuliffe asks, taking the note from Lt. Col. Ned Moore, his chief of staff.

“No,” Moore corrects him. “They want us to surrender.”

McAuliffe laughs and begins to read.

The letter is dated December 22, 1944:

To the U.S.A. Commander of the encircled town of Bastogne,

The fortune of war is changing. This time the U.S.A. forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units. More German armored units have crossed the river Ourthe near Ortheuville, have taken Marche and reached St. Hubert by passing through Hompre-Sibret-Tillet. Libramont is in German hands. There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender of the encircled town. In order to think it over a term of two hours will be granted beginning with the presentation of this note.

If this proposal should be rejected, one German artillery corps and six heavy A.A. battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne. The order for firing will be given immediately after this two hours’ term.

All the serious civilian losses caused by this artillery fire would not correspond with the well known American humanity.

The German Commander.

McAuliffe looks at his staff. “Well, I don’t know what to tell them.”

“That first remark of yours would be hard to beat,” replies Lt. Col. Harry Kinnard, in his Texas twang.

“What do you mean?” McAuliffe responds.

“Sir, you said ‘nuts.’”

McAuliffe mulls it over. He knows his history, and suspects the moment will be memorialized. One French general refused to surrender at the Battle of Waterloo with the far more crass response of “Merde.”9

And so the response is quickly typed: “To the German Commander, ‘Nuts!’ The American Commander.”

When the letter is presented to the German emissaries, they don’t understand. “What is this, ‘nuts’?” asks Henke. The Germans have grown cold and arrogant while awaiting a response. They fully expected to return to their lines as heroes for effecting the surrender.

Col. Paul Harper, regimental commander of the 327th, has been tasked with delivering McAuliffe’s response. He orders the men into his jeep and drives them back to the no-man’s-land between the 101st Airborne and the Wehrmacht lines. “It means you can go to hell,” he tells the Germans as he drops them off.

“And I’ll tell you something else,” he adds. “If you continue to attack we will kill every goddamn German that tries to break into this city.”

Henke translates to the others. The Germans snap to attention and salute. “We will kill many Americans,” Henke responds. “This is war.”

“On your way, bud,” snorts Harper.

9

FONDATION PESCATORE

LUXEMBOURG CITY, LUXEMBOURG

DECEMBER 23, 1944

9:00 A.M.

George S. Patton takes off his helmet as he enters the century-old Catholic chapel. Though Episcopalian, he is in need of a place to worship. The sound of his footsteps echoes off the stone floor as he walks reverently to the foot of the altar. The scent of melting wax from the many votive candles fills the small chamber. Patton kneels, unfolding the prayer he has written for this occasion, and bows his head.

“Sir, this is Patton talking,” he says, speaking candidly to the Almighty. “The past fourteen days have been straight hell. Rain, snow, more rain, more snow—and I am beginning to wonder what’s going on in Your headquarters. Whose side are You on anyway?”

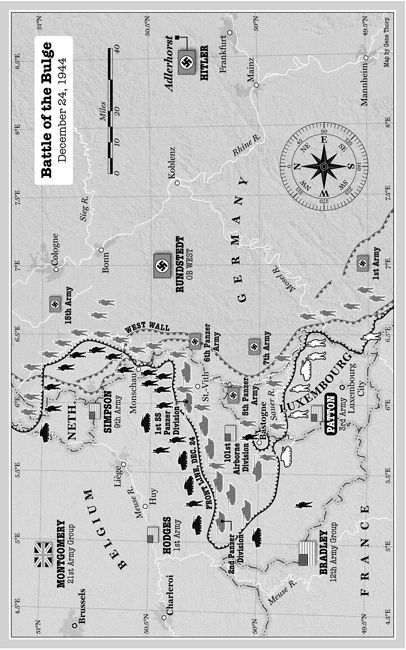

Patton and the Third Army are now thirty-three miles south of Bastogne. Every available man under his command has joined this race to rescue the city. The Bulge in the American lines is sixty miles deep and thirty miles wide, with Bastogne an American-held island in the center. And while Patton’s men have so far been successful in maintaining their steady advance, there is still widespread doubt that he can succeed. Outnumbered and outgunned by the Germans, Patton faces the daunting challenge of attacking on icy roads in thick snow, with little air cover. Small wonder that British commander Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery—whom Patton has taken to calling a “tired little fart”—and other British authorities are quietly mocking Patton’s advance. He has even heard that many of them are suggesting he hold his lines and not attack, as Monty is doing, for fear that the wily German field marshal Gerd von Rundstedt may be preparing to launch yet another surprise attack that could do irreparable damage to the Allies. “Hold von Rundstedt?” Patton grumbled in reply. “I’ll take von Rundstedt and shove him up Montgomery’s ass.”

Despite those hard words, the truth is that the Third Army may be in trouble. Patton has vowed to Tony McAuliffe and the 101st Airborne that he will be in Bastogne on Christmas Day. However, thanks to the weather, it is very likely he will not be able to keep this promise.

So the general prays.

“For three years my chaplains have been telling me that this is a religious war. This, they tell me, is the Crusades all over again, except that we’re riding tanks instead of chargers. They insist that we are here to annihilate the Germans and the godless Hitler so that religious freedom may return to Europe. Up until now I have gone along with them, for You have given us Your unreserved cooperation. Clear skies and a calm sea in Africa made the landings highly successful and helped us to eliminate Rommel. Sicily was comparatively easy and You supplied excellent weather for the armored dash across France, the greatest military victory that You have thus far allowed me. You have often given me excellent guidance in difficult command situations and You have led German units into traps that made their elimination fairly simple.

“But now You’ve changed horses midstream. You seem to have given von Rundstedt every break in the book, and frankly, he’s beating the hell out of us. My army is neither trained nor equipped for winter warfare. And as You know, this weather is more suitable for Eskimos than for southern cavalrymen.

“But now, Sir, I can’t help but feel that I have offended You in some way. That suddenly You have lost all sympathy for our cause. That You are throwing in with von Rundstedt and his paper-hanging god [Hitler]. You know without me telling You that our situation is desperate. Sure, I can tell my staff that everything is going according to plan, but there’s no use telling You that my 101st Airborne is holding out against tremendous odds in Bastogne, and that this continual storm is making it impossible to supply them even from the air. I’ve sent Hugh Gaffey, one of my ablest generals, with his 4th Armored Division, north toward that all-important road center to relieve the encircled garrison and he’s finding Your weather more difficult than he is the Krauts.”

* * *

This isn’t the first time Patton has resorted to divine intervention. Every man in the Third Army now carries a three-by-five card that has a Christmas greeting from Patton on one side and a special prayer for good weather on the other. The general firmly believes that faith is vital when it comes to doing the impossible. Patton sees no theological conflict in asking God to allow him to kill the enemy. He has even given the cruel order that all SS soldiers are to be shot rather than taken prisoner.

* * *

“I don’t like to complain unreasonably,” Patton continues his prayer, “but my soldiers from Meuse to Echternach are suffering tortures of the damned. Today I visited several hospitals, all full of frostbite cases, and the wounded are dying in the fields because they cannot be brought back for medical care.”