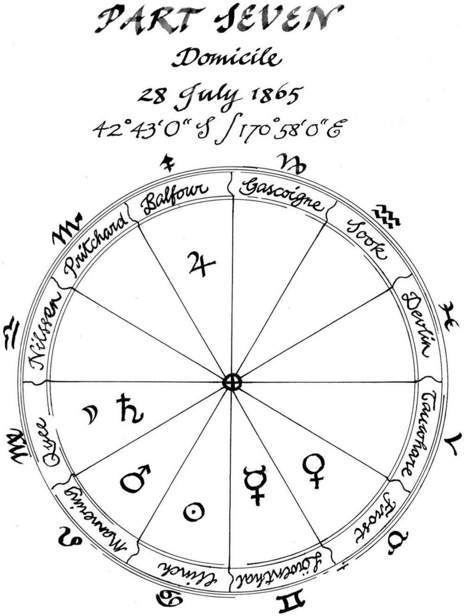

CANCER & THE MOON

In which Edgar Clinch attempts to exercise his authority, having deduced that Anna’s recent decline in health owes much to a new dependency both facilitated and encouraged by her employer, Mannering; and Anna Wetherell, whose obstinacy of feeling is more than a match for Clinch’s own, does not indulge him.

‘I don’t have anything against the Chinese,’ said Clinch. ‘I just don’t like the look of it, that’s all.’

‘What does it matter what it looks like?’

‘I don’t like the feel of it. That’s what I meant. The situation.’

Anna smoothed down the skirt of her dress—muslin, with a cream skirt and a crocheted bust, one of five that she had purchased from the salvage vendors following the wreck of the Titania some weeks ago. Two of the gowns had been speckled with black mould, the kind that any amount of washing would not remove. They were all very heavy, and the corsets, very fortified, tokens by which she presumed them to be relics of an older, more rigid age. The salvage man, as he wrapped the purchases in paper, had informed her that, very strangely, the Titania had been conveying no female passengers at all on the day she came to ground; stranger still, nobody had come forward to claim this particular trunk after the cargo had been recovered from the wreck. None of the shipping firms seemed to know the first thing about it. The bill of lading had been rendered illegible by salt water, and the log did not list the item by name. It was certainly a mystery, the salvage man concluded. He hoped that she would not come to any embarrassment or difficulty, in wearing them.

Clinch pressed on. ‘How are you to keep your wits about you, when you’re under? How are you to defend yourself, if—if—well, if you encounter something—untoward?’

Anna sighed. ‘It isn’t your concern.’

‘It’s my concern when I can see plain as day that he’s got your advantage, and he’s using you for ill.’

‘He will always have my advantage, Mr. Clinch.’

Clinch was becoming upset. ‘Where did it come from—your thirst? Answer me that! You just picked up a pipe, did you, and that was all it took? Why did you do it, if you weren’t compelled by Mr. Mannering himself? He knows the way he wants you: without any room to move, that’s how. Do you think I haven’t seen it before, this method? The other girls won’t touch the stuff. He knows that. But he tried it on you. He set you up. He took you there.’

‘Edgar—’

‘What?’ said Clinch. ‘What?’

‘Please leave me be,’ said Anna. ‘I can’t bear it.’

THE LEO SUN

In which Emery Staines enjoys a long luncheon with the magnate Mannering, who, over the past month, has made a concerted effort to court his friendship, behaving mayorally, as he prefers to do, as though all goldfields triumphs are his to adjudicate, and his to commend.

‘You’re a man who wears his success, Mr. Staines,’ said Mannering. ‘That’s a uniform I like.’

‘I’m afraid,’ said Staines, ‘my luck has been rather awfully exaggerated.’

‘That’s modesty talking. It was a hell of a find, you know, that nugget. I saw the banker’s report. What did it fetch—a hundred pounds?’

‘More or less,’ said Staines, uncomfortably.

‘And you picked it up in the gorge, you said!’

‘Near the gorge,’ Staines corrected. ‘I can’t remember exactly where.’

‘Well, it was a piece of good luck, wherever it came from,’ said Mannering. ‘Will you finish up these mussels, or shall we move on to cheese?’

‘Let’s move on.’

‘A hundred pounds!’ said Mannering, as he signalled to the waiter to come and take their plates away. ‘That’s a d—n sight more than the price of the Gridiron Hotel, whatever you paid for the freehold. What did you pay?’

Staines winced. ‘For the Gridiron?’

‘Twenty pounds, was it?’

He could hardly dissemble. ‘Twenty-five,’ he said.

Mannering slapped the table. ‘There you have it. You’re sitting on a pile of ready money, and you haven’t spent a single penny in four weeks. Why? What’s your story?’

Staines did not answer immediately. ‘I have always considered,’ he said at last, ‘that there is a great deal of difference between keeping one’s own secret, and keeping a secret for another soul; so much so that I wish we had two words, that is, a word for a secret of one’s own making, and a word for a secret that one did not make, and perhaps did not wish for, but has chosen to keep, all the same. I feel the same about love; that there is a world of difference between the love that one gives—or wants to give—and the love that one desires, or receives.’

They sat in silence for a moment. Then Mannering said, gruffly, ‘What you’re telling me is that this isn’t the whole picture.’

‘Luck is never the whole picture,’ said Staines.

AQUARIUS & SATURN

In which Sook Yongsheng, having recently taken up residence in Kaniere Chinatown, journeys into Hokitika to outfit himself with various items of hardware, where he is observed by the gaoler George Shepard, known to him as the brother of the man he had been accused of having murdered, and also, as the husband of that man’s true murderer, Margaret.

Margaret Shepard stood in the doorway of the hardware store, waiting for her husband to complete his purchases and pay; Sook Yongsheng, though not eight feet distant from her, was shielded from her view by the dry goods cabinet. Shepard, coming around the side of the cabinet, saw him first. He stopped at once, and his expression hardened; in a voice that was quite ordinary, however, he said,

‘Margaret.’

‘Yes, sir,’ she whispered.

‘Go back to the camp,’ said Shepard, without taking his eyes from Sook Yongsheng. ‘At once.’

She did not ask why; mutely she turned and fled. When the door had slammed shut behind her, Shepard’s right hand moved, very slowly, to rest upon his holster. In his left hand he was holding a paper sack containing a roll of paper, two hinges, a ball of twine, and a box of bugle-headed nails. Sook Yongsheng was kneeling by the paraffin cans, making some kind of calculation on his fingers; he had placed his parcels beside him on the floor.

Shepard was aware, dimly, that the atmosphere in the store had become very still. From somewhere behind him someone said, ‘Is there a problem, sir?’

Shepard did not answer at once. Then he said, ‘I will take these.’ He held up the paper sack, and waited; after a moment he heard whispering, and then tentative footsteps approaching, and then the sack was lifted from his hand. Nearly a minute passed. Sook Yongsheng continued counting; he did not look up. Then the same voice said, almost in a whisper, ‘That will be a shilling sixpence, sir.’

‘Charge it to the gaol-house,’ Shepard said.

JUPITER’S LONG REIGN

In which Alistair Lauderback, believing his half-brother Crosbie Wells to be the half-brother, on his mother’s side, of the blackguard Francis Carver, and believing, consequently, that Crosbie Wells had been in some way complicit in the blackmail under which he, Lauderback, surrendered his beloved barque Godspeed, is perplexed to receive a letter with a Hokitika postmark, the contents of which make clear that his apprehension has been quite false, a revelation that prompts him, after a great deal of solemn contemplation, to write a letter of his own.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the renewed correspondence of Mr. Crosbie Wells comprised the sole reason for Alistair Lauderback’s decision to run for the Westland seat in Parliament; the letter did serve, however, to tip the scales in the district’s favour. Lauderback read the letter through six times, then, sighing, tossed it onto his desk, and lit his pipe.