The general told my father that they were carrying out door-to-door searches throughout Swat and monitoring the borders. He said they knew that the people who had targeted me came from a gang of twenty-two Taliban men and that they were the same gang who had attacked Zahid Khan, my father’s friend who had been shot two months earlier.

My father said nothing but he was outraged. The army had been saying for ages that there were no Taliban in Mingora and that they had cleared them all out. Now this general was telling him that there had been twenty-two of them in our town for at least two months. The army had also insisted Zahid Khan was shot in a family feud and not by the Taliban. Now they were saying I had been targeted by the same Taliban as him. My father wanted to say, ‘You knew there were Taliban in the valley for two months. You knew they wanted to kill my daughter and you didn’t stop them?’ But he realised it would get him nowhere.

The general hadn’t finished. He told my father that although it was good news that I had regained consciousness there was a problem with my eyesight. My father was confused. How could the officer have information he didn’t? He was worried that I would be blind. He imagined his beloved daughter, her face shining, walking around in lifelong darkness asking, ‘Aba, where am I?’ So awful was this news that he couldn’t tell my mother, even though he is usually hopeless at keeping secrets, particularly from her. Instead he told God, ‘This is unacceptable. I will give her one of my own eyes.’ But then he was worried that at forty-three years old his own eyes might not be very good. He hardly slept that night. The next morning he asked the major in charge of security if he could borrow his phone to call Colonel Junaid. ‘I have heard that Malala can’t see,’ my father told him in distress.

‘That’s nonsense,’ he replied. ‘If she can read and write, how can she not see? Dr Fiona has kept me updated, and one of the first notes Malala wrote was to ask about you.’

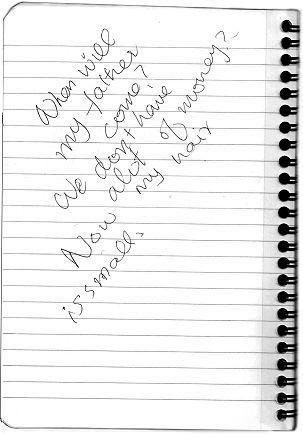

Far away in Birmingham, not only could I see but I was asking for a mirror. ‘Mirror,’ I wrote in the pink diary – I wanted to see my face and hair. The nurses brought me a small white mirror which I still have. When I saw myself, I was distraught. My long hair, which I used to spend ages styling, had gone, and the left side of my head had none at all. ‘Now my hair is small,’ I wrote in the book. I thought the Taliban had cut it off. In fact the Pakistani doctors had shaved my head with no mercy. My face was distorted like someone had pulled it down on one side, and there was a scar to the side of my left eye.

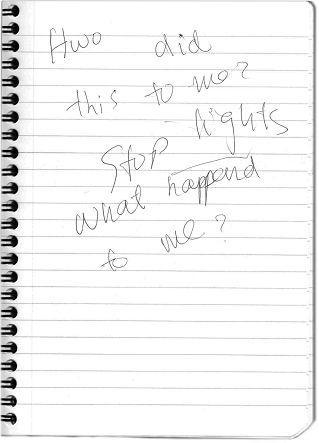

‘Hwo did this to me?’ I wrote, my letters still scrambled. ‘What happened to me?’

I also wrote ‘Stop lights’ as the bright lights were making my head ache.

‘Something bad happened to you,’ said Dr Fiona.

‘Was I shot? Was my father shot?’ I wrote.

She told me that I had been shot on the school bus. She said two of my friends on the bus had also been shot, but I didn’t recognise their names. She explained that the bullet had entered through the side of my left eye where there was a scar, travelled eighteen inches down to my left shoulder and stopped there. It could have taken out my eye or gone into my brain. It was a miracle I was alive.

I felt nothing, maybe just a bit satisfied. ‘So they did it.’ My only regret was that I hadn’t had a chance to speak to them before they shot me. Now they’d never hear what I had to say. I didn’t even think a single bad thought about the man who shot me – I had no thoughts of revenge – I just wanted to go back to Swat. I wanted to go home.

After that images started to swim around in my head but I wasn’t sure what was a dream and what was reality. The story I remember of being shot is quite different from what really happened. I was in another school bus with my father and friends and another girl called Gul. We were on our way home when suddenly two Taliban appeared dressed in black. One of them put a gun to my head and the small bullet that came out of it entered my body. In this dream he also shot my father. Then everything is dark, I’m lying on a stretcher and there is a crowd of men, a lot of men, and my eyes are searching for my father. Finally I see him and try to talk to him but I can’t get the words out. Other times I am in a lot of places, in Jinnah Market in Islamabad, in Cheena Bazaar, and I am shot. I even dreamed that the doctors were Taliban.

As I grew more alert, I wanted more details. People coming in were not allowed to bring their phones, but Dr Fiona always had her iPhone with her because she is an emergency doctor. When she put it down, I grabbed it to search for my name on Google. It was hard as my double vision meant I kept typing in the wrong letters. I also wanted to check my email, but I couldn’t remember the password.

On the fifth day I got my voice back but it sounded like someone else. When Rehanna came in we talked about the shooting from an Islamic perspective. ‘They shot at me,’ I told her.

‘Yes, that’s right,’ she replied. ‘Too many people in the Muslim world can’t believe a Muslim can do such a thing,’ she said. ‘My mother, for example, would say they can’t be Muslims. Some people call themselves Muslims but their actions are not Islamic.’ We talked about how things happen for different reasons, this happened to me, and how education for females not just males is one of our Islamic rights. I was speaking up for my right as a Muslim woman to be able to go to school.

*

Once I got my voice back, I talked to my parents on Dr Javid’s phone. I was worried about sounding strange. ‘Do I sound different?’ I asked my father.

‘No,’ he said. ‘You sound the same and your voice will only get better. Are you OK?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘but this headache is so severe, I can’t bear the pain.’

My father got really worried. I think he ended up with a bigger headache than me. In all the calls after that he would ask, ‘Is the headache increasing or decreasing?’

After that I just said to him, ‘I’m OK.’ I didn’t want to upset him and didn’t complain even when they took the staples from my head and gave me big injections in my neck. ‘When are you coming?’ I kept asking.

By then they had been stuck in the army hostel at the hospital in Rawalpindi for a week with no news about when they might come to Birmingham. My mother was so desperate that she told my father, ‘If there is no news by tomorrow I will go on a hunger strike.’ Later that day my father went to see the major in charge of security and told him. The major looked alarmed. Within ten minutes my father was told arrangements would be made for them to move to Islamabad later that day. Surely there they could arrange everything?

When my father returned to my mother he said to her, ‘You are a great woman. All along I thought Malala and I were the campaigners but you really know how to protest!’

They were moved to Kashmir House in Islamabad, a hostel for members of parliament. Security was still so tight that when my father asked for a barber to give him a shave, a policeman sat with them all the way through so the man wouldn’t cut his throat.

At least now they had their phones back and we could speak more easily. Each time, Dr Javid would call my father in advance to tell him what time he could speak to me and to make sure he was free. But when the doctor called the line was usually busy. My father is always on the phone! I rattled off my mother’s eleven-digit mobile number and Dr Javid looked astonished. He knew then that my memory was fine. But my parents were still in darkness about why they weren’t flying to me. Dr Javid was also baffled as to why they weren’t coming. When they said they didn’t know, he made a call and then assured them the problem was not with the army but the civilian government.