This “technological elite” of MIT-trained students played a central role in the development of science and technology in post-Independence India:

In the first forty years of independence, MIT graduates occupied an astounding number of the highest-level positions in the Indian technical community — more than graduates of any other single school in the United States or the United Kingdom, and quite possibly more than the graduates of any single school in India.54

Under Jawaharlal Nehru’s leadership, beginning in 1951, the government began setting up the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), designed from the start to provide world-class scientific and technological education on a meritocratic, heavily subsidized basis. The institutes were necessarily built with foreign aid, but the manner in which this aid was acquired and used was designed to reflect the country’s nonaligned status during the Cold War. After the first institute at Kharagpur, each campus had one national sponsor — the USSR provided support for IIT Bombay, and West Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom followed with Madras, Kanpur, and Delhi respectively. MIT created and anchored a consortium of nine American universities that joined the Kanpur Indo-American Program in 1961. It was through this program that the first computer arrived in India: in July 1963, a chartered DC-7 flew an IBM 1620 mainframe to a military airbase in Kanpur.55

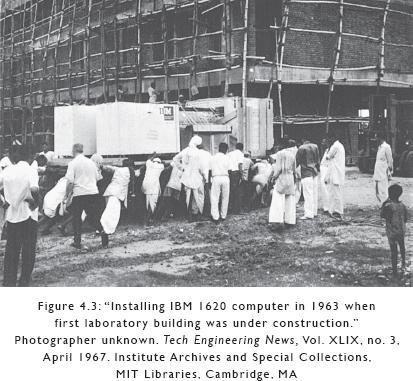

A photograph of the arrival of the computer on the IIT campus (figure 4.3) has all the solemn symbolism and poignant hope and pathos of a history painting. The computer itself comprises two enormous white cuboid masses that flank a large console panel. The 1620 sits on a wheeled flatbed platform that is pushed by a crowd of dhoti-clad Indian men into a building still wrapped in a framework of rope-hitched bamboo stilts (used by construction workers and painters). An older man in Western clothes — white short-sleeved shirt, dark pants, shoes — hurries from right to left with a rather supervisory air. As always, a gaggle of onlookers watches the proceedings. And at the very edge of the frame, at the bottom right, a boy in shorts — eight years old? Ten? — cups his hand over his face.

The building in the picture is the computer center of the permanent campus of IIT Kanpur, which was still under construction. “The centrality of the computer to the plans for IIT Kanpur,” Ross Bassett tells us, “is indicated by the fact that the delivery of the 1620 was scheduled for the earliest possible date.”56 So, a small “technological elite”—the “suited and booted,” in Indian parlance — led by Nehru, made a visionary decision to pour vast amounts of wealth and skills into institutions aimed at the future and in large part motivated by the recent past, by the knowledge that technological lag in the subcontinent at a crucial historical moment had led to the defeats and depredations of industrialized colonialism, a gigantic plundering which was begun and extended for its first hundred years not by a nation state but by a modern corporation, the Honourable East India Company. The Indian leaders built the institutes and brought computers into a country that had an abundance of cheap labor — those men in dhotis — and a desperate need for development. A half-century later, the questions asked then are still pertinent: Should the nation expend its resources on such institutions while people starve? Do we need computers or tractors? In any drawing room or village square today, you can hear the rueful lament, “We can put satellites in orbit but can’t get clean drinking water to two hundred and fifty million people.” What became of that boy in the picture? Was his life improved by the creation of the institutes? The consequences — salutary or otherwise — of the setting up of the institutes are of course embedded in the tangled skein of recent Indian history, intertwined and inseparable from all the myriad ambiguous narratives of growth, corruption, hope, and disappointment that followed Independence.

As a young boy myself, I believed the Institutes would save us; I pinned my hopes on the newly built steel plants, the irrigation projects, the huge hydroelectric dams, the factories that sprang up on the edges of cities. My mother’s mother lived in a village which still lacked electricity, but even there you could see signs of change, a tractor or two, a newly built road. I knew the Institutes had computers, but I never saw one until I came to the States. Our “progress,” our “development,” was fragmented and piecemeal — some people became very rich, but many remained poor.

What is abundantly, unambiguously clear is that the Nehruvian vision, evangelized outwards from Kanpur and the other institutes, succeeded in its stated aim of producing “world-class” engineers, so much so that the world tempted them away from Gandhi’s country with siren songs of well-stocked laboratories, abundant resources, and wealth. This famous “brain drain,” which once so irritated some IIT faculty that they refused to write recommendation letters to American universities for their students, has been reimagined as “brain circulation” with attendant flows of remittances and expertise back to the home country. As Indian geeks have gained prominence and power abroad — especially in Silicon Valley — they have been instrumental in driving and facilitating investments by international companies in India. In the American computer industry, the presence of Indians is impossible to miss — by 2005, Indians had created 26 percent of all immigrant-founded tech start-ups in the US. By 2012, this percentage had increased to 33.2 percent, more than the next eight ethnic groups combined (immigrants from China, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Israel, Russia, Korea, and Australia).57 In a 2013 interview, the executive chairman of Google, Eric Schmidt, said, “Forty percent of the startups in Silicon Valley are headed by India-based entrepreneurs.”58 And, according to Vinod Khosla, IIT graduate and co-founder of Sun Microsystems, “Microsoft, Intel, PCs, Sun Microsystems — you name it, I can’t imagine a major area where Indian IIT engineers haven’t played a leading role.”59

The ubiquity of the Indian geek has been recognized even by popular American media in the figure of Raj Koothrappali, a character on the television show The Big Bang Theory. Raj is an astrophysicist at Caltech; he is mild, socially awkward, especially around women; he is effeminate by American standards (the other characters frequently suspect him of being gay); his parents try to run his life, so his attempts to live as an independent adult form one of the show’s running gags. “Koothrappali” is a Malayalam last name, or at least “Koothrappallil” is, so I’m guessing that Raj is supposed to be a south Indian, but he could well be the modern version of Sir Lepel Griffin’s hapless Bengali. These broad strokes catch precisely the larger culture’s notions of geeky Indianness, which — especially within the machismo of the IT industry — sometimes become a liability for Indians. In his autobiographical book, Dude, Did I Steal Your Job? Debugging Indian Programmers, N. Sivakumar recalls the advice he received when he first arrived in the US for a programming gig:

One of my friends advised me to walk smart. He told me that Americans think we are very humble and not smart enough to handle a crisis. He said that the way we walk in the company corridors itself portrays the shabbiness of Indians …

Most of the consulting companies and personal advisers tell the Indian programmers to behave smart and bold. They also advise them to be more aggressive, positive, and outspoken, so that Americans will love them. Most Indians lack all of these good qualities. Indians are no match to Americans when it comes to the above skills.60