In 1865 Hunt married Fanny Waugh. They left England together in August 1866, but during quarantine in Florence, Fanny gave birth to a boy and died shortly afterwards. Hunt returned to England in September 1867 and paid homage to Fanny the next year by returning to Florence. In 1869 Hunt was elected a member of the Royal Watercolour Society, which also counted Edward Burne-Jones among its members. In August of the same year he returned to Jerusalem. His next great religious painting was The Shadow of Death of 1871, an imaginary incident in the life of Jesus. Weary after a day of work, Jesus raises his arms, which cast the shadow of his coming crucifixion on the wall, thus frightening his mother.

In 1875, after marrying the sister of his deceased wife, Hunt returned to Jerusalem where he began his painting The Triumph of the Innocents, which was one of the most important works of his life. The subject is an imaginary episode of the Flight into Egypt where the Holy Family is accompanied by a procession of innocents illuminated by a supernatural light. After coming back to London in 1878, he preferred to show his works in galleries or exhibitions less public than the Royal Academy.

The first retrospective of his work took place in London in 1886. He was awarded the Order of Merit in 1905 and published his autobiography.

Holman Hunt occupies a slightly different position to that of other artists, and he was not at all affected by art movements after 1850. He possessed a strong and constant personality and used particular working methods, and his stated ambition was to “serve as high priest and expounder of the excellence of the works of the Creator.” He devoted too much time to each of his works to make very many, but their power makes up for their small number.

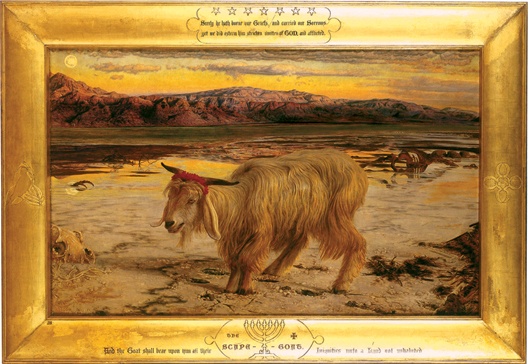

William Holman Hunt,

The Scapegoat, 1854-1855.

Oil on canvas, 87 x 139.8 cm.

Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight.

John Everett Millais, Mrs. James Wyatt

Jr. and her Daughter, Sarah, c. 1850.

Oil on mahogany, 35.3 x 45.7 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

William Holman Hunt,

John Everett Millais, 1853.

Pastel and colour chalk, 32.7 x 24.8 cm.

National Portrait Gallery, London.

Sir John Everett Millais

(Southampton, 1829 - London, 1896)

From very early on in life, Millais demonstrated an exceptional gift for painting. In Jersey, where he spent most of his childhood, he briefly attended school before being dismissed. His mother then took charge of his education, placing a particular accent on history, literature, and poetry. He later said that it was she who taught him everything. The local drawing teacher, Mr Bessell, gave him a basic artistic education. At that time, the German painter Edward Henry Wehnert lived in the region, and he also participated in Millais’ education. In 1835 the Millais family moved to Dinan in Brittany, where the young John Everett drew officers of the Dinan garrison with great skill. Realising his potential, the family decided to move to London to allow the young artist’s talent to completely develop. At nine years old, he was introduced to the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Martin Archer Shee, who predicted that he would conquer the art world. He studied at Henry Sass Preparatory Art Academy in Bloomsbury and, at the age of eleven, he was the youngest student to enter the Academy, where he obtained numerous prizes and honours. He met Hunt in 1844, and in 1846 he exhibited his painting Pizarro seizing the Inca of Peru at the Royal Academy. At the beginning of 1848, Millais, Hunt and Rossetti, disappointed by the theory and practices of English art, which they found too conventional and academic, initiated the Pre-Raphaelite movement, hoping to break with tradition. According to Millais, Pre-Raphaelitism had a single purpose; to “present Nature on the canvas.” The first painting he made in accord with this principle was the banquet scene inspired by Keats’ poem Isabella (1849). Millais devoted all his effort to painting the minute details of nature and the characters in this painting. The story is told forcefully and the expressions of the figures are captivating.

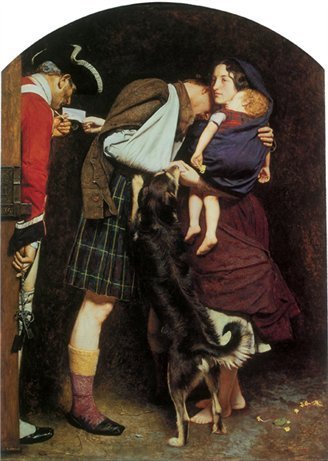

John Everett Millais,

The Order of Release 1746, 1852-1853.

Oil on canvas, 102.9 x 73.7 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

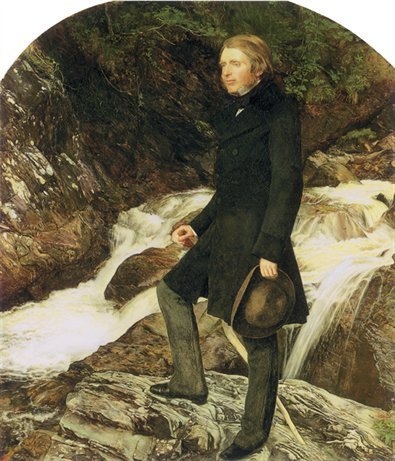

John Everett Millais,

Portrait of John Ruskin, 1853-1854.

Oil on canvas, 78.7 x 68 cm.

Private Collection.

His painting Christ in the Home of his Parents depicts an imaginary incident in the life of Jesus, treated in a simple and realistic manner, which provoked religious as well as artistic authorities. Charles Dickens described this Christ as a “hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy”, and The Times called the painting “disgusting”. The rest of his strictly Pre-Raphaelite paintings such as Mariana, A Huguenot, and Ophelia were greeted with less hostility, thanks to Millais’ growing renown and the support of John Ruskin, who espoused the Pre-Raphaelites’ cause in his letters to The Times and in his articles on Pre-Raphaelitism. In 1851, Millais, who had until then refused to read Modern Painters, in which the principles of Pre-Raphaelitism were presented, met Ruskin and his wife Euphemia (Effie). With his brother William, in July 1853, he left for Callander in Scotland for three months, accompanied by the Ruskins. During this trip he fell in love with Effie and painted a portrait of Ruskin standing in front of a landscape, thus illustrating the critic’s attitudes toward Nature and the future. In 1854 Effie obtained the annulment of her marriage to Ruskin, making it possible for her to marry Millais in 1855. The young couple moved into Annat Lodge where Millais painted Autumn Leaves, whose light and colour deeply moved Ruskin. The couple’s first child, Everett, was born the next year. From 1860 to 1869, he devoted all of his creative energy to making more than eighty illustrations for the novels of Anthony Trollope, thus becoming the most prolific illustrator of the 1860s in England. In 1863 Millais was elected a member of the Royal Academy, an institution derided by the Pre-Raphaelites. Having progressively distanced himself from the Pre-Raphaelites, he finally separated himself from them completely to turn toward such great masters as Rembrandt and Velázquez, and to paint the portraits of influential people. Millais always had the support of the public. When he left Pre-Raphaelitism for sentimental, expressive painting, he was followed by an even larger crowd. When he abandoned expressive subjects for portraits, the crowd continued to grow, and he finally moved on to nudes. Fame reached out to him and tirelessly protected him for forty-five years. He also contributed to the creation of the National Portrait Gallery and encouraged Henry Tate to found the eponymous Tate Gallery. Millais never refused honours; he accepted the Légion d’Honneur from the French government in 1868, and in 1885 Queen Victoria raised him to a baronetcy. The apex of his career was his election as President of the Royal Academy in 1896. After suffering from throat cancer for several years, he died in August 1896 and was buried at Saint Paul’s Cathedral. Millais was one of the greatest painters of his time and devoted his virtuosity and power to breathing new energy into English painting.