“No fucking kidding,” Kowalski griped.

Susan ignored him, her eyes on the lake. Her voice lowered. “It will be like Christmas Island. Only a hundredfold worse…trapped inside the cavern. And you’ll all be exposed.”

Lisa did not doubt it. Already her skin itched.

“You must go.” Susan steadied enough to gain her feet, leaning a hand on the wall. “Only I can be here. I must be here.”

Lisa saw the fear shining in her eyes, but also the dead certainty.

“For the cure?” Lisa said.

Susan nodded. “I must be exposed one more time, by the source here. I can’t say how I know, but I do.” She lifted a palm to the side of her head. “It’s…it’s like I’m living one foot in the past, one foot here. It’s hard to stay here. Everything is filling me up, every thought, sensation. I can’t turn it off. And I…I feel it expanding.”

Again the fear shone brighter in her eyes.

Susan’s description reminded Lisa of autism, a neurological inability to shut off the flow of sensory input. But a few autistic patients were also idiot savants, geniuses in narrow fields, their brilliance born out of their rewiring. Lisa tried to imagine the pathophysiology that must be occurring inside Susan’s brain, awash in strange biotoxins, energized by the bacteria that produced the toxins. Humans only used a small fraction of their brain’s neural capacity. Lisa could almost picture Susan’s EEG of her brain, afire, energized.

Susan stumbled to the water’s edge. “We only have this one chance.”

“Why?” Gray asked, stepping alongside her.

“After the lake reaches critical mass and erupts with its full toxic load, it will exhaust itself. It will take three years before the lake will be ready again.”

“How do you know that?” Gray asked.

Susan glanced to Lisa for help.

“She just knows,” Lisa answered. “She’s somehow connected to this place. Susan, is that why you were so urgent about getting here?”

Susan nodded. “Once opened to sunlight, the lake will build to a blow. If I missed it…”

“Then the world would be defenseless for three years. No cure. The pandemic would spread around the world.” Lisa imagined the microcosm aboard the cruise ship expanded across the globe.

The horror was interrupted by Seichan’s return, pounding up to them, breathless, her face shining damply. “I found a door.”

“Then go,” Susan urged. “Now.”

Seichan shook her head. “Couldn’t open it.”

Kowalski pantomimed. “Did you try giving it a hard shove?”

Seichan rolled her eyes, but she did nod her head. “Yes, I tried shoving it.”

Kowalski threw his hands high, surrendering. “Well, that’s all I got.”

“But there was a cross carved above the stone archway,” Seichan continued. “And an inscription, but it’s too dark to read. The words might offer some clue.”

Gray turned to the monsignor.

“I still have my flashlight,” Vigor said. “I’ll go with her.”

“Hurry,” Gray urged.

Already the air was getting difficult to breathe. The glow in the lake had spread far, sliding along the length of the spar toward shore.

Susan pointed to it. “I must be out on the lake.”

They headed toward the peninsula of rock.

Gray paced Lisa. “You mentioned a trespassed biosystem earlier. Mind telling me what the hell you think is really going on here?” He waved to the glowing lake, to Susan.

“I don’t know everything, but I’m pretty sure I know who all the key players are.”

Gray nodded for her to continue.

Lisa pointed to the glow. “It all started here, the oldest organism in the story. Cyanobacteria. Precursors to modern plants. They’ve penetrated every environmental niche: rock, sand, water, even other organisms.” She nodded to Susan. “But that’s getting ahead of the story. Let’s start here.”

“This cavern.”

She nodded. “The cyanobacteria invaded this sinkhole, but remember they needed sunlight, and the cavern is mostly dark. The hole above was probably even smaller originally. To thrive here, they needed another source of energy, a food source. And cyanobacteria are innovative little adapters. They had a ready source of food above in the jungle…they just needed a way to get to it. And nature is anything if not ingenious at building strange interrelationships.”

Lisa related the story she had once told Dr. Devesh Patanjali, about the Lancet liver fluke, how its life cycle utilized three hosts: cattle, snail, and ant.

“At one point, the liver fluke even hijacks its ant host. It compels the ant to climb a blade of grass, lock its mandible, and wait to be eaten by a grazing cow. That’s how strange nature is. And what happened here is no less strange.”

As Lisa continued, she appreciated being able to talk through her theories. She took a moment to explain Henri Barnhardt’s assessment of the Judas Strain, how he classified the virus into a member of the Bunyavirus family. She remembered Henri’s diagram, describing a linear relationship from human to arthropod to human.

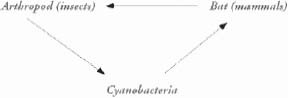

“But we were wrong,” Lisa said. “The virus took a page out of the fluke’s handbook. Three hosts come into play here.”

“If cyanobacteria are the first hosts,” Gray asked, “what’s the second host in this life cycle?”

Lisa stared toward the plugged opening in the roof and kicked some of the dried bat guano. “The cyanobacteria needed a way to fly the coop. And since they were already sharing this cavern with some bats, they took advantage of those wings.”

“Wait. How do you know they used the bats?”

“The Bunyavirus. It loves arthropods, which include insects and crustaceans. But strains of Bunyavirus can also be found in mice and bats.”

“So you think the Judas Strain is a mutated bat virus?”

“Yes. Mutated by the cyanobacteria’s neurotoxins.”

“But why?”

“To drive the bats crazy, to scatter them out into the world, carrying a virus that invades the local biosphere through its bacteria. Basically turning each bat into a little biological bomb. Laying waste wherever it lands. If Susan is correct, the pool would send out these bio-bombs every three years, allowing the environment to replenish itself in between.”

“But how does that serve the cyanobacteria if the disease kills birds and animals outside the cavern?”

“Ah, because it utilizes a third host, another accomplice. Arthropods. Remember, arthropods are already the preferred host for Bunyaviruses. Insects and crustaceans. They also happen to be nature’s best scavengers. Cleaning up the dead. Which is what the virus compelled them to do. By first making them ravenously hungry…”

Lisa’s words stumbled as she remembered the cannibalism aboard the ship. She fought to stay clinical, to be understood. “After stimulating this hunger, ensuring a thorough cleanup, the virus rewired the host to return here, to this cavern, to haul their catch and bring it to the pit, to feed the bacterial pool. They had no choice. Similar to the fluke and the ant. A neurological compulsion, a migratory urge.”

“Like Susan,” Gray said.

Lisa grew grim at the comparison. She pictured in her head the life cycle she had just described. Triangular rather than linear: cyanobacteria, bats, and arthropods. All joined together by the Judas Strain.

“Susan is different,” Lisa said. “Man was never supposed to be part of this life cycle. But being mammalian, like the bat, we’re susceptible to the toxins, to the virus. So when the Khmer discovered this cavern, we inadvertently became a part of that life cycle, taking the place of the bats. Spreading via our two legs instead of wings. Sickening the population every three years, triggering epidemics of varying severity.”

Gray stared toward Susan. “But what about her? Why did she survive?”