Today, the ship lies 24 feet beneath street level. Lining the construction fence on the streets above are hundreds of spectators drawn to the incongruous spectacle of a ship lying deep in the heart of San Francisco’s financial district. Whether you approach San Francisco by air or sea, or by car across the Bay Bridge, the view is dominated by the high rises of the financial district as they march up from the Embarcadero to the slopes of Telegraph, Nob and Russian hills. The distinctive profile of the Transamerica Pyramid rises above some of the city’s few standing survivors of its youth. The relatively low two- and three-story brick buildings of Jackson Square are the last visible remnants of San Francisco’s infamous “Barbary Coast,” survivors of the 1906 earthquake, fires and urban renewal. They are survivors from another era, perched in the midst of a modern city.

Directly beneath the financial district lies an immense archeological deposit that dates back to the origins of San Francisco during the gold rush. Six major fires and innumerable smaller conflagrations have devastated the city. After the destruction wrought by the fires, entire burnt districts were filled over. The debris of those fires lies buried beneath the modern city. The astonishing collection of items that came to be buried beneath San Francisco attracted comment even during the gold rush. The San Francisco Evening Picayune, on September 30, 1850, remarked: “At some future period, when the site of San Francisco may be explored by a generation ignorant of its history, it will take its place by the side of Herculaneum and Pompeii, and furnish many valuable relics to perplex the prying Antiquarian. Buried in the streets, from six to ten feet beneath the surface, there is already a stratum of artificial productions which the entombed cities of Italy cannot exhibit. Knives, forks, spoons, chisels, files, and hardware of every description, gathered from the places of several conflagrations. Masses of nails exhibiting volcanic indications, stove plates and tin ware, empty bottles by the cartload and hundreds of other miscellanies, lie quietly and deeply interred in Sacramento Street, and perhaps will be carefully exhumed in days to come, and be distributed over the world as precious relics!” The Evening Picayune’s smug prophecy did not take long to come true. As early as the 1870s, excavation for construction unearthed relics of the gold rush period. The transient nature of San Francisco ensured that most residents were ignorant of the particulars of its past — and the “discoveries” that arose from beneath the streets and sidewalks delighted them.

Now, I stand watching the high-pressure hose strip away the shroud of mud and sand as history emerges from the buried ashes of a long-ago fire. The oak planks of the ship’s hull are solid, and the wood is bright and fresh. Even more amazing is the stench of burned wood and sour wine rising from the charred debris. A century and a half ago mud, water and sand sealed the wreckage of the ship so perfectly that time has stood still.

The product of the venerable New England seafaring town of Newburyport, Massachusetts, General Harrison was launched from the banks of the Merrimack River in the spring of 1840. Built for a group of local merchants, General Harrison worked as a coastal packet out of Boston and New York, running south to New Orleans with passengers and cargo, then returning north with southern cotton. In 1846, the ship’s owners sold her to a consortium of well-known and moneyed Charlestown residents who had mercantile links to Pacific Coast ports from Chile to Alaska as well as Hawaii and China. The new owners sent General Harrison on a sixteen-month voyage around the world. After trading at Valparaiso, Tahiti, Hawaii and Hong Kong, she returned to New York in 1847. A new owner, Thomas H. Perkins, Jr., son of America’s richest man of the day, kept the ship in his fleet until 1849, the year of the exciting news that gold had been discovered in California.

The gold discovery sparked a “rush” for California’s riches. The editors of the New York Herald remarked in early January that the “spirit of emigration which is carrying off thousands to California… increases and expands every day. All classes of our citizens seem to be under the influence of this extraordinary mania… Poets, philosophers, lawyers, brokers, bankers, merchants, farmers, clergymen — all are feeling the impulse and are preparing to go and dig for gold and swell the number of adventurers to the new El Dorado.”

Most gold-seekers chose to travel to California by ship, and between December 1848 and December 1849, 762 vessels sailed from American ports for San Francisco. One of them was General Harrison. Sailing from Boston on August 3, 1849, the ship rounded Cape Horn to reach the Chilean port of Valparaiso. There, the ship’s agents, Mickle y Compañia, loaded merchandise from Chile’s farms, wineries and shops to sell in San Francisco. On February 3, 1850, the ship reached San Francisco. With her passengers off to the gold fields and her cargo sold, General Harrison would have been ready for another voyage. But the lure of gold was too much for her crew, who deserted and headed for the mines, leaving General Harrison, along with hundreds of other ships, idle on the San Francisco docks.

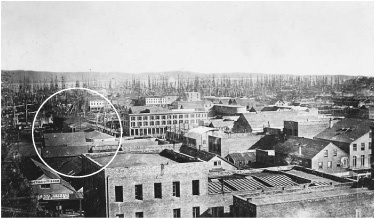

The waterfront was then a constantly growing, hectic center of activity. Every day, more ships arrived, workers landed cargoes, and thousands of men crowded the sandy streets seeking passage up the bay and its tributaries to the heart of the gold country. Crowded beyond its capacity, San Francisco was boxed in on all sides by massive, shifting sand dunes and a shallow cove that was by turns either a stagnant pond or an expanse of thick foul mud at low tide. The city’s entrepreneurs solved the problem of lack of space by building on top of the shallows of the cove. Thousands of pilings, shipped south from the forests of British Columbia and Puget Sound, were pounded into the shallows, enabling long wharves to march across the mud flats to the anchorage. Alongside the wharves, buildings were perched atop piles, and ships were hauled up onto the mud to serve the needs of the booming frontier town.

By the time of General Harrison’s arrival, a Chilean visitor to San Francisco described the city as “a Venice built of pine instead of marble. It is a city of ships, piers, and tides. Large ships with railings, a good distance from the shore, served as residences, stores, and restaurants… The whole central part of the city swayed noticeably because it was built on piles the size of ship’s masts driven down into the mud.”

The frequent fires that ravaged San Francisco exacerbated the city’s need for buildings. Etting Mickle, who was in charge of the local branch of Mickle y Compañia, bought (eneral Harrison to serve as the company’s “store ship,” or floating warehouse. Just a block west lay the Niantic, beached in August 1849 and converted into a store ship by friends of Mickle’s. Workers removed General Harrison’s masts and hauled her up onto the mud flats alongside the Clay Street wharf. Nestled in the mud, her hull still washed by the tide, the ship was quickly converted into a warehouse. Carpenters built a large “barn” on the deck and cut doors into the hull, while laborers cleaned out the hold to store crates, barrels and boxes of merchandise. Mickle advertised, on May 30, 1850, that “this fine and commodious vessel being now permanently stationed at the corner of Clay and Battery streets was in readiness to receive stores of any description, and offers a rare inducement to holders of goods.”