Now, those paintings rested at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. “As these pictures are very sensitive to injury and need care,” Panin wrote, he was sending an officer, Major Thier, to co-ordinate a search with the Swedes. “I do not doubt that you will do your utmost as this matter concerns her Majesty the Empress personally,” Panin told the Swedish royal chancellor.

Thier’s trip to Finland was in vain. Winter was fast approaching, and little could be done. The Swedes sent a number of expeditions out to the archipelago to search for the wreck. Boats towed grappling irons to try and snag the hulk, but the vast area and deep seas made it an impossible task. An obstruction at 30 fathoms was repeatedly snagged by searchers, but it proved to be a rock. The Swedes and Russians abandoned their efforts to find Vrouw Maria, and the ship, despite the rumors of riches aboard, was in time forgotten.

We’re anchored above a small wooden shipwreck that Finnish researchers believe is Vrouw Maria. The story of the tiny Dutch ship with her secret cargo of precious paintings resurfaced in 1982, when Christian Ahlstro m, Finland’s leading shipwreck researcher and historian, discovered the tale while working through Swedish diplomatic records. Ahlstro m spent years meticulously reconstructing the tale of Vouw Maria, and his discoveries encouraged diver and researcher Rauno Koivusaari to start searching for the wreck in 1998. In June 1999, while towing a side-scan sonar behind his ship Teredo, Koivusaari finally located the intact wreck of a small wooden ship near Jurmo Island.

Under Finnish law, all such finds are the property of the state. Koivusaari reported the discovery to the Maritime Museum of Finland, which acts on behalf of the National Board of Antiquities. The museum conducted a two-week survey of the exterior of the wreck in the summer of 2000. Lying in a deep hole surrounded by rocks, the wreck was missing its rudder and the deck hatches were open. Reaching inside the main cargo hatch, archeologists carefully recovered three clay tobacco pipes, a metal ingot and small round lead seal. A clay bottle lying on the deck was also mapped and recovered.

Back in the laboratory of the maritime museum, analysis of the artifacts showed the researchers that they were on the right track. The pipes were Dutch, and one of them had a maker’s mark that indicated the pipe was made by Jan Souffreau of Gouda, Holland, whose factory was in business from 1732 to 1782. The ingot was zinc, and Vrouw Maria was known to have been carrying nearly forty “ship pounds” of that metal. The lead seal, probably from twine that wrapped a bale of cloth, was marked “Leyden,” from the Dutch town of the same name. The clay bottle, no older than the 1760s, held mineral water from the German town of Trier.

But more work was needed. The museum assembled a team under the direction of senior curator and archeologist Saalamaria Tikkanen, who invited The Sea Hunters to participate in the first detailed look both inside and outside the wreck.

We’re aboard the research vessel Teredo, heading for the site of the wreck of Vrouw Maria with an expert team of Finns who are volunteering their time, and archeologists Matias Laitenen and Minna Koivikko. I’m here with The Sea Hunters to join the expedition and to film the work of the Finnish team as part of our television series. We’re all excited by the uniqueness of the wreck of Vrouw Maria and her story, and by the fact that, despite its importance, the story is not well known outside Scandinavia. That’s about to change. Our producer and team leader, John Davis, helps Mike Fletcher suit up for his dive. Mike’s son Warren and my daughter Beth both haul gear and work to prepare for Mike’s 140-foot plunge into darkness. We rig Mike’s helmet, lights and underwater video camera.

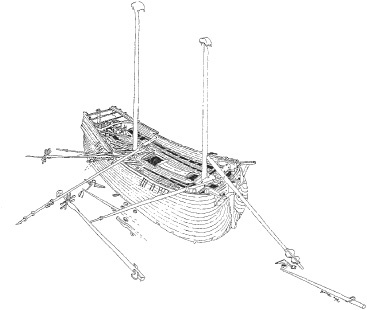

As we watch a small color monitor on Teredo’s bridge, it’s almost as though we’re there when Mike jumps off the ship and starts his fall into the depths. The water is clear, and soon the form of the wreck comes into view. The rounded hull sits nearly level on the bottom, with a slight list to starboard. The lower part of the masts rise halfway to the surface, and one anchor rests against the port side of the hull. The ship is surprisingly intact, thanks to the special conditions of the Baltic. Vrouw Maria is an example, like the famous Swedish warship Vasa, of how the Baltic’s waters preserve old shipwrecks. Vasa capsized and sank in Stockholm harbor in 1628. Swedish researchers discovered the intact hulk and raised it in 1961. Stained black with age, but looking just as she did when she sailed nearly four centuries ago, Vasa is one of the world’s great archeological treasures and one of Sweden’s major tourist attractions in its own museum on the Stockholm waterfront.

The Baltic preserved Vasa and Vrouw Maria so well because it is a deep, cold sea with a low salinity level. In some areas, the Baltic is practically fresh water because of the many lakes and rivers that drain into it, and cold fresh water preserves wood better than salt water. But most important, the low salinity levels keep out the teredo navalis, a sea worm that eats wood and will consume a wooden wreck within a matter of decades. That’s why we’re all smiling at the wry Finnish humor evident in naming their research vessel Teredo. But unlike its namesake worm, this vessel’s mission is to document and preserve wrecks. The fact that when the Swedes raised Vasa, they found coils of rope, leather shoes and a crock of still-edible butter inside the ship, provides some hope about the state of Vrouw Maria’s precious cargo after more than a couple of centuries in the water.

As Mike makes his way around the wreck, we are able to follow, step by step, the actions of Reynoud Lorentz and his nine-man crew as they struggled to save the cargo. It becomes increasingly clear, as we carefully survey the wreck, that this is Vrouw Maria. The stern is damaged — rudder missing and planks broken. It’s not enough damage to quickly fill the ship, but it is enough to slowly flood her. The ship appears to have sunk at anchor, and we know that Lorentz and his crew had anchored Vrouw Maria before the last time they left her. They believed that the thick anchor cables had parted and that the ship had drifted off and sunk, but we can see that the ship filled and sank by the bow, practically on top of an anchor.

Air trapped inside the sinking ship’s stern damaged it when she sank. The quarterdeck was ripped free, leaving the captain’s cabin an empty shell. A hatch at the back of the stern burst open, and loose planks litter the seabed. Yet the sinking did little to disturb the decks, though some of the planks are missing, others loose, again perhaps part of the frantic work by the crew to pull cargo out of the flooded hold. Loose bits of rigging — blocks, tackle, a coil of rope and the ship’s sounding lead, used to determine the depth of water — lie against the starboard rail, perhaps where the crew stowed them as they worked to salvage the ship. Looking at the lead line, I think of the entries in the logbook for October 3, 1771, when Lorentz wrote that after hitting the rock, they “sounded and could not find the bottom,” a scary proposition. But working the ship “with great difficulty,” they “sounded again to approximately 13 fathoms, dropped the anchor, which gave way for a long while, we let out the whole rope and it finally began to hold, we fastened the sails and all hands went to the pump.” The lead line on the deck is a reminder that time is standing still on the bottom of the Baltic.