Tears streaked down Vic’s face as she ran across the sand, remembering.

Two men. Laughing. Beer on their breaths. Strong arms from building and making. Strong arms for tearing and taking. Laughing. Her screams were funny to them. Her arms weak. But the way she squirmed made them roar. And Vic could hear her friends shouting through the walls, shouting now for them to stop, rattling locked doors, yelling at the people in another room, where similar horrors were more habit than happenstance.

Loose sand. Vic reached the end of intact houses, the extent of the onrush of that great dune. She ran past people gazing, people watching, people standing still, not helping, not hearing the muffled screams, the calloused hands over pretty mouths, the beer-breath lips crushing down, the feeling of sand piled on, of being buried alive, a pressure against new parts of her, the first time, crushing, crushing.

She hurried up the slope of sand until her legs were sore and would barely obey. She angled for where the Honey Hole used to sit. Vic pulled her band on, flipped her visor down, powered up her suit as she dove forward. She disappeared into the sand with barely a splash. Down where she was free and nothing could pin her.

Bright objects everywhere. The yellow and orange of great spoils, a scrounger’s paradise, so much worth saving. There were riches here carried all the way from the great wall. The rich were here as well. Vic saw a form trapped ahead of her, probably too late, but she formed a column of sand beneath the body and sent it to the surface. There were entire homes buried and flattened. There was debris everywhere to dodge. And ahead of her, right where she’d been running, was the three-story building she remembered, the house of nightmares, completely encased by the dune. No one would ever be harmed in that building again. They already had been. They already had been. The place was full of sand.

Vic slid through a busted window, hardening the sand around her to protect herself from the shards of glass. The walls inside were askew. The building had nearly buckled. It might have buckled were it not for the low concrete wall on the back side of the building to hold back the sand. Vic dialed her visor down to account for the loose pack inside the Honey Hole. Too bright in there. Bodies everywhere. Chairs and tables and the flash of glass jars and bottles. She raced up through the great hall and over the railing—or where the railing once stood. A purplish pocket of air along the third floor. The sand only got so high. Vic started to move who she could toward the air, but there wasn’t enough time. Not enough time. Even if the people there had gotten a lungful when it happened. Even if they had closed their mouths. Dead in minutes. Her mom was gone. Never got to say goodbye.

Vic saw the door to the room where it had happened all those years ago. The door was still whole, still solid, still closed on what took place in there. No one knew but those who had been inside. No one. Suffocating.

In her visor, her suit’s power glowed a bright green. A full charge. Ready for a deep dive, all that extra juice for holding the world at bay, for holding up that column of sand and air that was always pressing down on her, pressing down. Vic only had breath enough in her lungs for another minute or two. Her heart was racing, burning through her oxygen, not prepared for this. Not ready to see this. Not ready for her mother to die.

She couldn’t scream beneath the sand. There were no divers to hear the shouts rising up in her throat. Nowhere for that rage to go. But something inside Vic burst, something like a great wall meant to hold back the years and years. It toppled all at once, anger flowing outward, a power she’d honed in the deepest of sand now surging through her suit. That power exploded; it raged in the deadly spill from that tumbling dune; and the muscle to lift a motor, a car, to rip the roof off an ancient skyscraper, billowed forth.

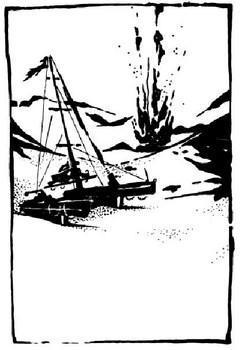

There was a rumbling in the earth, a swelling, a press of sand from beneath, and the Honey Hole creaked upward, out of the spill, Vic screaming and crying beneath the sand where no diver could hear her, hands curled into claws of rage and effort, the sand spilling into her mouth and onto her tongue, sand soaked in beer and tasting of the awful past, and a grumble, a grumble as the world tilted and walls popped and sand flowed from orifices, out of windows and doors, flowing like warm honey, like blood and milk, draining from that awful place where the past had long been buried, as the Honey Hole rose out of the desert and settled, shuddering, atop the dunes.

The Honey Hole—full of the spitting and coughing and bewildered and dead—was sickeningly saved. And Vic, exhausted again in that place, terrified and weeping, collapsed to the ground outside her mother’s door, her mother’s open door, blood coming only from her ears and nose this time.

Part 5:

A Rap Upon Heaven’s Gate

45 • A Quiet Dawn

There was a distant thrum. The sound of drums, of bootfalls, of a god’s mighty pulse. Conner knew that sound. It reminded him of the thunder far east. It was the muffled roar of rebel bombs, a noise that came before chaos and death and red dunes and a mother’s wails. Conner dropped his spoon into his bowl of stew, pushed away from the beer-soaked table in the Honey Hole, and ran toward the stairs to warn his mom.

He took the steps two at a time. His brother Rob chased after him. There were more of the muffled blasts in the distance as they raced down the balcony. Danger outside. Violence. Or maybe it was nothing. Maybe it was cannon fire to celebrate the discovery of Danvar. Conner almost felt silly for running to his mother, a child doing what boys did in a panic, turning to a parent to save them, to tell them what to do.

He threw open her door, knew there were no clients inside, just his half-sister Violet who had emerged from No Man’s Land. And as he stepped into the room, Conner felt a rumble in the earth, felt it through his father’s boots, and he knew what was happening. He knew that this was more than the usual bombs. That great roar and that impossibly loud hiss meant the sands were coming for them all.

And in the brief flutter between two beats of his heart, as the din grew and grew, as his mother yelled for the boys to run, to hold their breath, to move, Conner thought only of diving onto the bed, of protecting the girl he’d spent the last two days looking after. He bolted across the room, Rob on his heels, got halfway there, when the wall of sand slammed into the Honey Hole.

The floor beneath Conner’s feet lurched sideways—a god snatching a rug out from under him. He tumbled. There was a crash of wood and tin, an explosion of glass, a sudden blindness as all light was extinguished by a press of solid dune, a splintering sound, and then the desert sands pouring in around Conner and his family.

He barely heard his mother scream for them to hold their breaths before he was smothered. Sand was in his nose and against his lips. He was frozen, pinned to the floor in a sprawl, the weight of ten bullies on his back, a sense, nearby, right beside him, of his brother Rob. Just a memory of where his brother had been—where his mother had been—before the sand had claimed them.

Pitch black. A residual warmth in the sand from having been outside in the sun. Complete silence. Just his pulse, which he could feel in his neck as it was squeezed by the drift. The pulse in his temples. No room to expand his chest. Couldn’t swallow. Hands around his throat. His brother nearby. And not enough room even to cry. Just a coffin to be terrified in. A place for dying. For panic. For muscles and tendons raging and flexing but not budging an inch—what a paralyzed person must feel. What everyone who has ever been buried alive must feel. This is how they go. This is how they go. This is how they go. Conner couldn’t stop thinking it. The dead had been bodies in the sand before. But now he could feel what they had felt. They had felt just like this, frozen and terrified and not able to move their jaws even to sob for their mothers.