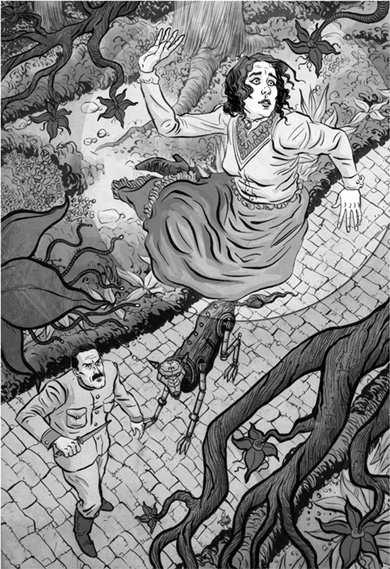

“MY GOD!” VRONSKY SHOUTED, AT LAST NOTICING: “ANNA! YOU ARE FLOATING!”

After Anna had assured Vronsky for the third time that she had suffered nothing but minor bruising in the fall, they sat beside each other upon the stone wall beside the tree.

She turned his face to hers, looking him squarely in the eye. With the intensity brought on by peril, they focused and listened to one another.

“I cannot lose my son,” Anna began simply.

“But, for God’s sake, which is better?-leave your child, or keep up this degrading position?”

“To whom is it degrading?”

“To all, and most of all to you.”

As they spoke, Lupo padded carefully around the tree, sniffing at the earth, gathering up fragments of the translucent sheath for later analysis.

“You say degrading… don’t say that. That has no meaning for me.” Her voice shook. She did not want him now to say what was untrue. She had nothing left but his love, and she wanted to love him. “Don’t you understand that from the day I loved you everything has changed for me? For me there is one thing, and one thing only-your love. If that’s mine, I feel so exalted, so strong, that nothing can be humiliating to me. I am proud of my position, because… proud of being… proud…” She could not say what she was proud of. Tears of shame and despair choked her utterance. She stood still and sobbed.

He, too, felt, something swelling in his throat and twitching in his nose, and for the first time in his life Vronsky found himself on the point of weeping. The flower-trap; his love; their impossible situation; he could not have said exactly what it was that touched him so. He felt sorry for her, and he felt he could not help her, and with that he knew that he was to blame for her wretchedness, and that he had done something wrong.

“Is not a divorce possible?” he said feebly. She shook her head, not answering. “Couldn’t you take your son, and still leave him?”

“Yes; but it all depends on him. Now I must go to him,” she said shortly. Her presentiment that all would again go on in the old way had not deceived her.

“On Tuesday I shall be in Petersburg, and everything can be settled.”

“Yes,” she said. “But don’t let us talk any more of it.”

Anna’s carriage, which she had sent away and ordered to come back to the little gate of the Vrede Garden, drove up. Anna said good-bye to Vronsky. Android Karenina gingerly lifted her up into their carriage, and they drove home.

CHAPTER 10

ON MONDAY THERE WAS the usual sitting of the Higher Branches of the Ministry. Alexei Alexandrovich walked into the hall where the sitting was held, greeted the members and the president as usual, and sat down in his place, the papers laid ready before him. Among these papers lay the necessary evidence and a rough outline of the speech he intended to make. But he did not really need these documents. He remembered every point, and did not think it necessary to go over in his memory what he would say. He knew that when the time came, and when he saw his enemy facing him, and studiously endeavoring to assume an expression of indifference, his speech would flow of itself better than he could prepare it now. The Face murmured quiet encouragement into his cerebral cortex, assuring him that the import of his speech was of such magnitude that every word of it would have weight. Meanwhile, as he listened to the usual report, he had the most innocent and inoffensive air. No one, looking at him gazing calmly through the monocle he wore, somewhat pompously, over his one human eye, and at the air of weariness with which his head drooped on one side, would have suspected that in a few minutes a torrent of words would flow from his lips that would arouse a fearful storm, set the members shouting and attacking one another, and force the president to call for order.

When the report was over, Alexei Alexandrovich announced in his subdued, delicate voice that he had several points to bring before the meeting in regard to the subsequent phases of the Project they had undertaken. All attention was turned upon him. Alexei Alexandrovich cleared his throat, and not looking at his opponent, but selecting, as he always did while he was delivering his speeches, the first person sitting opposite him, an inoffensive little old man who never had an opinion of any sort in the commission, began to expound his views.

“As those of you who have, like myself, been participants in the development of the Project are aware, the first phase of our noble endeavor has been a total and unqualified success.”

SO IT HAS BEEN, hissed the Face. SO I HAVE BEEN.

“The second phase is now being made ready, under my direct supervision, in a subterranean work office in the Moscow Tower. The new prototype of robot, exactly as I planned, will have those three advancements we wished for: advancements in appearance, advancements in capacity, and advancements in the appropriate distribution of loyalty.”

This set of euphemistic and jargonistic phrases earned a smattering of applause from Karenin’s colleagues. But when he reached the point about the next phase of the Project, in which all Class III robots extant in Russian society would be gathered up and adjusted to meet the new standard, his opponent jumped up and began to protest. Stremov took the position that only those individuals who so desired it should have their Class Ills updated to the new version that Karenin was perfecting. Stremov, who had long been Karenin’s political enemy, was a man of fifty, partly gray, but still vigorous-looking, very ugly, but with a characteristic and intelligent face. He spoke longly and loudly about “ancient prerogatives” and the “unique nature of the bond between man and beloved-companion,” and altogether a stormy sitting followed. But Alexei Alexandrovich triumphed, and his motion was carried, the oath of secrecy-unto-death was sworn; Alexei Alexandrovich’s success had been even greater than he had anticipated.

Next morning, Tuesday, Alexei Alexandrovich, on waking up, recollected with pleasure his triumph of the previous day, and he could not help smiling. Absorbed in this pleasure, Alexei Alexandrovich had completely forgotten that it was Tuesday, the day fixed by him for the return of Anna Arkadyevna, and he was surprised and received a shock of annoyance when a II/Footman/74 motored in to inform him of her arrival.

Anna had arrived in Petersburg early in the morning; the carriage had been sent to meet her in accordance with her communiqué, and so Alexei Alexandrovich might have known of her arrival. But when she arrived, he did not meet her. She sent word to her husband that she had come, went to her own room, and occupied herself in sorting out her things, expecting he would come to her. But an hour passed; he did not come. She went into the dining room on the pretext of giving some directions, and spoke loudly on purpose, expecting him to come out there; but he did not come, though she heard him go to the door of his study. She knew that he usually went out quickly to his office, and she wanted to see him before that, so that their attitude to one another might be defined.

She walked across the drawing room and went resolutely to him. When she went into his study he was in official uniform, obviously ready to go out, sitting at a little table on which he rested his elbows, looking dejectedly before him. She saw him before he saw her, and she saw that he was thinking of her.

On seeing her, he would have risen, but changed his mind, then his metal faceplate rapidly radiated through a sequence of colors, from cruel red to a harsh, gleaming gold-an affect Anna had never seen before, and she thought to herself: It is growing. All the time it is growing.