«Stop!» cried Virginia, stamping her foot, «it is you who are rude, and horrid, and vulgar, and as for dishonesty, you know you stole the paints out of my box to try and furbish up that ridiculous blood–stain in the library. First you took all my reds, including the vermilion, and I couldn't do any more sunsets, then you took the emerald–green and the chrome–yellow, and finally I had nothing left but indigo and Chinese white, and could only do moonlight scenes, which are always depressing to look at, and not at all easy to paint. I never told on you, though I was very much annoyed, and it was most ridiculous, the whole thing; for who ever heard of emerald–green blood?»

«Well, really,» said the Ghost, rather meekly, «what was I to do? It is a very difficult thing to get real blood nowadays, and, as your brother began it all with his Paragon Detergent, I certainly saw no reason why I should not have your paints. As for colour, that is always a matter of taste: the Cantervilles have blue blood, for instance, the very bluest in England; but I know you Americans don't care for things of this kind.»

«You know nothing about it, and the best thing you can do is to emigrate and improve your mind. My father will be only too happy to give you a free passage, and though there is a heavy duty on spirits of every kind, there will be no difficulty about the Custom House, as the officers are all Democrats. Once in New York, you are sure to be a great success. I know lots of people there who would give a hundred thousand dollars to have a grandfather, and much more than that to have a family ghost.»

«I don't think I should like America.»

«I suppose because we have no ruins and no curiosities,» said Virginia, satirically.

«No ruins! no curiosities!» answered the Ghost; «you have your navy and your manners.»

«Good evening; I will go and ask papa to get the twins an extra week's holiday.»

«Please don't go, Miss Virginia,» he cried; «I am so lonely and so unhappy, and I really don't know what to do. I want to go to sleep and I cannot.»

«That's quite absurd! You have merely to go to bed and blow out the candle. It is very difficult sometimes to keep awake, especially at church, but there is no difficulty at all about sleeping. Why, even babies know how to do that, and they are not very clever.»

«I have not slept for three hundred years,» he said sadly, and Virginia's beautiful blue eyes opened in wonder; «for three hundred years I have not slept, and I am so tired.»

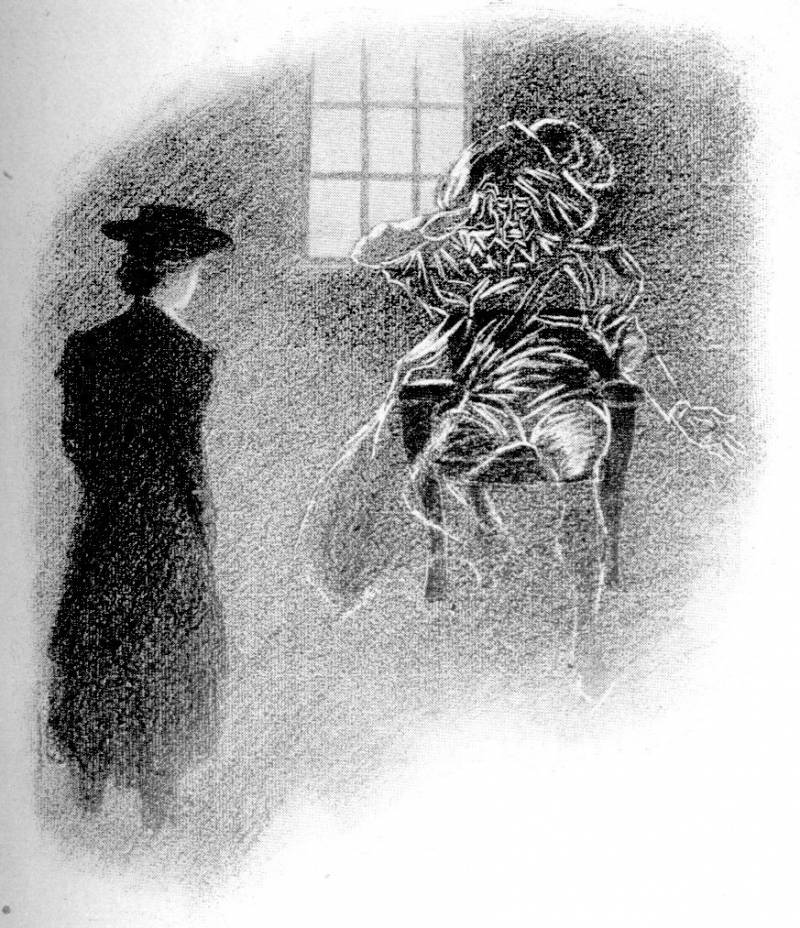

Virginia grew quite grave, and her little lips trembled like rose–leaves. She came towards him, and kneeling down at his side, looked up into his old withered face.

«Poor, poor Ghost,» she murmured; «have you no place where you can sleep?»

"'POOR, POOR GHOST,' SHE MURMURED; 'HAVE YOU NO PLACE WHERE YOU CAN SLEEP?'"

«Far away beyond the pine–woods,» he answered, in a low, dreamy voice, «there is a little garden. There the grass grows long and deep, there are the great white stars of the hemlock flower, there the nightingale sings all night long. All night long he sings, and the cold crystal moon looks down, and the yew–tree spreads out its giant arms over the sleepers.»

Virginia's eyes grew dim with tears, and she hid her face in her hands.

«You mean the Garden of Death,» she whispered.

«Yes, death. Death must be so beautiful. To lie in the soft brown earth, with the grasses waving above one's head, and listen to silence. To have no yesterday, and no to–morrow. To forget time, to forget life, to be at peace. You can help me. You can open for me the portals of death's house, for love is always with you, and love is stronger than death is.»

Virginia trembled, a cold shudder ran through her, and for a few moments there was silence. She felt as if she was in a terrible dream.

Then the ghost spoke again, and his voice sounded like the sighing of the wind.

«Have you ever read the old prophecy on the library window?»

«Oh, often,» cried the little girl, looking up; «I know it quite well. It is painted in curious black letters, and is difficult to read. There are only six lines:

But I don't know what they mean.»

«They mean,» he said, sadly, «that you must weep with me for my sins, because I have no tears, and pray with me for my soul, because I have no faith, and then, if you have always been sweet, and good, and gentle, the angel of death will have mercy on me. You will see fearful shapes in darkness, and wicked voices will whisper in your ear, but they will not harm you, for against the purity of a little child the powers of Hell cannot prevail.»

Virginia made no answer, and the ghost wrung his hands in wild despair as he looked down at her bowed golden head. Suddenly she stood up, very pale, and with a strange light in her eyes. «I am not afraid,» she said firmly, «and I will ask the angel to have mercy on you.»

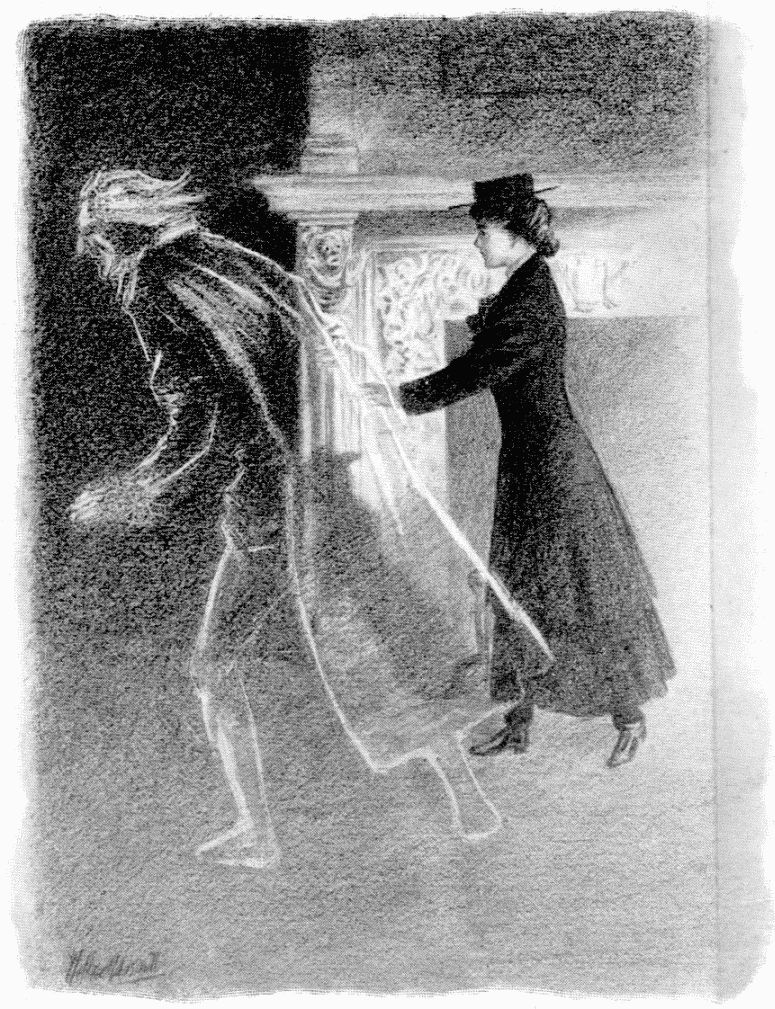

He rose from his seat with a faint cry of joy, and taking her hand bent over it with old–fashioned grace and kissed it. His fingers were as cold as ice, and his lips burned like fire, but Virginia did not falter, as he led her across the dusky room. On the faded green tapestry were broidered little huntsmen. They blew their tasselled horns and with their tiny hands waved to her to go back. «Go back! little Virginia,» they cried, «go back!» but the ghost clutched her hand more tightly, and she shut her eyes against them. Horrible animals with lizard tails and goggle eyes blinked at her from the carven chimneypiece, and murmured, «Beware! little Virginia, beware! we may never see you again,» but the Ghost glided on more swiftly, and Virginia did not listen. When they reached the end of the room he stopped, and muttered some words she could not understand. She opened her eyes, and saw the wall slowly fading away like a mist, and a great black cavern in front of her. A bitter cold wind swept round them, and she felt something pulling at her dress. «Quick, quick,» cried the Ghost, «or it will be too late,» and in a moment the wainscoting had closed behind them, and the Tapestry Chamber was empty.

"THE GHOST GLIDED ON MORE SWIFTLY"

VI

About ten minutes later, the bell rang for tea, and, as Virginia did not come down, Mrs. Otis sent up one of the footmen to tell her. After a little time he returned and said that he could not find Miss Virginia anywhere. As she was in the habit of going out to the garden every evening to get flowers for the dinner–table, Mrs. Otis was not at all alarmed at first, but when six o'clock struck, and Virginia did not appear, she became really agitated, and sent the boys out to look for her, while she herself and Mr. Otis searched every room in the house. At half–past six the boys came back and said that they could find no trace of their sister anywhere. They were all now in the greatest state of excitement, and did not know what to do, when Mr. Otis suddenly remembered that, some few days before, he had given a band of gipsies permission to camp in the park. He accordingly at once set off for Blackfell Hollow, where he knew they were, accompanied by his eldest son and two of the farm–servants. The little Duke of Cheshire, who was perfectly frantic with anxiety, begged hard to be allowed to go too, but Mr. Otis would not allow him, as he was afraid there might be a scuffle. On arriving at the spot, however, he found that the gipsies had gone, and it was evident that their departure had been rather sudden, as the fire was still burning, and some plates were lying on the grass. Having sent off Washington and the two men to scour the district, he ran home, and despatched telegrams to all the police inspectors in the county, telling them to look out for a little girl who had been kidnapped by tramps or gipsies. He then ordered his horse to be brought round, and, after insisting on his wife and the three boys sitting down to dinner, rode off down the Ascot road with a groom. He had hardly, however, gone a couple of miles, when he heard somebody galloping after him, and, looking round, saw the little Duke coming up on his pony, with his face very flushed, and no hat. «I'm awfully sorry, Mr. Otis,» gasped out the boy, «but I can't eat any dinner as long as Virginia is lost. Please don't be angry with me; if you had let us be engaged last year, there would never have been all this trouble. You won't send me back, will you? I can't go! I won't go!»