“Good.”

“Was it awful?”

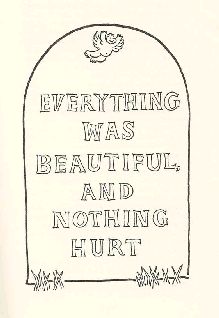

“Sometimes.” A crazy thought now occurred to Billy. The truth of it startled him. It would make a good epitaph for Billy Pilgrim — and for me, too.

“Would you talk about the war now, if I wanted you to?” said Valencia. In a tiny cavity in her great body she was assembling the materials for a Green Beret.

“It would sound like a dream,” said Billy. “Other people’s dreams aren’t very interesting usually.”

“I heard you tell Father one time about a German firing squad.” She was referring to the execution of poor old Edgar Derby.

“Um.”

“You had to bury him?”

“Yes.”

Did he see you with your shovels before he was shot?”

“Yes.”

“Did he say anything?”

“No.”

“Was he scared?”

“They had him doped up. He was sort of glassy-eyed.”

And they pinned a target to him?”

A piece of paper,” said Billy. He got out of bed, said, “Excuse me”, went to the darkness of the bathroom to take a leak. He groped for the light, realized as he felt the rough wall that he had traveled back to 1944, to the prison hospital again.

The candle in the hospital had gone out. Poor old Edgar Derby had fallen asleep on the cot next to Billy’s. Billy was out of bed, groping along a wall, trying to find a way out because he had to take a leak so badly.

He suddenly found a door, which opened, let him reel out into the prison night. Billy was loony with time-travel and morphine. He delivered himself to a barbed-wire fence which snagged him in a dozen places. Billy tried to back away from it but the barbs wouldn’t let go. So Billy did a silly little dance with the fence, taking a step this way, then that way, then returning to the beginning again.

A Russian, himself out in the night to take a leak, saw Billy dancing — from the other side of the fence. He came over to the curious scarecrow, tried to talk with it gently, asked it what country it was from. The scarecrow paid no attention, went on dancing. So the Russian undid the snags one by one, and the scarecrow danced off into the night again without a word of thanks.

The Russian waved to him, and called after him in Russian, “Good-bye.”

Billy took his pecker out, there in the prison night, and peed and peed on the ground. Then he put it away again, more or less, and contemplated a new problem: Where had he come from, and where should he go now?

Somewhere in the night there were cries of grief. With nothing better to do, Billy shuffled in their direction. He wondered what tragedy so many had found to lament out of doors.

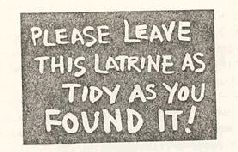

Billy was approaching, without knowing it, the back of the latrine. It consisted of a one-rail fence with twelve buckets underneath it. The fence was sheltered on three sides by a screen of scrap lumber and flattened tin cans. The open side faced the black tarpaper wall of the shed where the feast had taken place.

Billy moved along the screen and reached a point where he could see a message freshly painted on the tarpaper wall. The words were written with the same pink paint which had brightened the set for Cinderella. Billy’s perceptions were so unreliable that he saw the words as hanging in air, painted on a transparent curtain, perhaps. And there were lovely silver dots on the curtain, too. These were really nailheads holding the tarpaper to the shed. Billy could not imagine how the curtain was supported in nothingness, and he supposed that the magic curtain and the theatrical grief were part of some religious ceremony he knew nothing about.

Here is what the message said:

Billy looked inside the latrine. The wailing was coming from in there. The place was crammed with Americans who had taken their pants down. The welcome feast had made them as sick as volcanoes. The buckets were full or had been kicked over.

An American near Billy wailed that he had excreted everything but his brains. Moments later he said, “There they go, there they go.” He meant his brains.

That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.

Billy reeled away from his vision of Hell. He passed three Englishmen who were watching the excrement festival from a distance. They were catatonic with disgust.

“Button your pants!” said one as Billy went by.

So Billy buttoned his pants. He came to the door of the little hospital by accident. He went through the door, and found himself honeymooning again, going from the bathroom back to bed with his bride on Cape Ann.

“I missed you” said Valencia.

“I missed you,” said Billy Pilgrim.

Billy and Valencia went to sleep nestled like spoons, and Billy traveled in time back to the train ride he had taken in 1944 — from maneuvers in South Carolina to his father’s funeral in Ilium. He hadn’t seen Europe or combat yet. This was still in the days of steam locomotives.

Billy had to change trains a lot. All the trains were slow. The coaches stunk of coal smoke and rationed tobacco and rationed booze and the farts of people eating wartime food. The upholstery of the iron seats was bristly, and Billy couldn’t sleep much. He got to sleep soundly when he was only three hours from Ilium, with his legs splayed toward the entrance of the busy dining car.

The porter woke him up when the train reached Ilium. Billy staggered off with his duffel bag, and then he stood on the station platform next to the porter, trying to wake up.

“Have a good nap, did you?” said the porter.

“Yes,” said Billy.

“Man,” said the porter, “you sure had a hard-on.”

At three in the morning on Bill’s morphine night in prison, a new patient was carried into the hospital by two lusty Englishmen. He was tiny. He was Paul Lazzaro, the polka-dotted car thief from Cicero, Illinois. He had been caught stealing cigarettes from under the pillow of an Englishman. The Englishman, half asleep, had broken Lazzaro’s right arm and knocked him unconscious.

The Englishman who had done this was helping to carry Lazzaro in now. He had fiery red hair and no eyebrows. He had been Cinderella’s Blue Fairy Godmother in the play. Now he supported his half of Lazzaro with one hand while he closed the door behind himself with the other. “Doesn’t weigh as much as a chicken,” he said.

The Englishman with Lazzaro’s feet was the colonel who had given Billy his knock-out shot.

The Blue Fairy Godmother was embarrassed, and angry, too. “If I’d known I was fighting a chicken,” he said, “I wouldn’t have fought so hard.”

“Um.”

The Blue Fairy Godmother spoke frankly about how disgusting all the Americans were.

Weak, smelly, self-pitying — a pack of sniveling, dirty, thieving bastards,” he said. “They’re worse than the bleeding Russians.”

“Do seem a scruffy lot,” the colonel agreed.

A German major came in now. He considered the Englishmen as close friends. He visited them nearly every day, played games with them, lectured to them on German history, played their piano, gave them lessons in conversational German. He told them often that, if it weren’t for their civilized company, he would go mad. His English was splendid.

He was apologetic about the Englishmen’s having to put up with the American enlisted men. He promised them that they would not be inconvenienced for more than a day or two, that the Americans would soon be shipped to Dresden as contract labor. He had a monograph with him, published by the German Association of Prison Officials. It was a report on the behavior in Germany of American enlisted men as prisoners of war. It was written by a former American who had risen high in the German Ministry of Propaganda. His name was Howard W. Campbell, Jr. He would later hang himself while awaiting trial as a war criminal.