When Níniel and her company had gone, Brandir said to those that remained: ‘Behold how I am scorned, and all my counsel disdained! Choose you another to lead you: for here I renounce both lordship and people. Let Turambar be your lord in name, since already he has taken all my authority. Let none seek of me ever again either counsel or healing!’ And he broke his staff. To himself he thought: ‘Now nothing is left to me, save only my love of Níniel: therefore where she goes, in wisdom or folly, I must go. In this dark hour nothing can be foreseen; but it may well chance that even I could ward off some evil from her, if I were nigh.’

He girt himself therefore with a short sword, as seldom before, and took his crutch, and went with what speed he might out of the gate of the Ephel, limping after the others down the long path to the west march of Brethil.

CHAPTER XVII

THE DEATH OF GLAURUNG

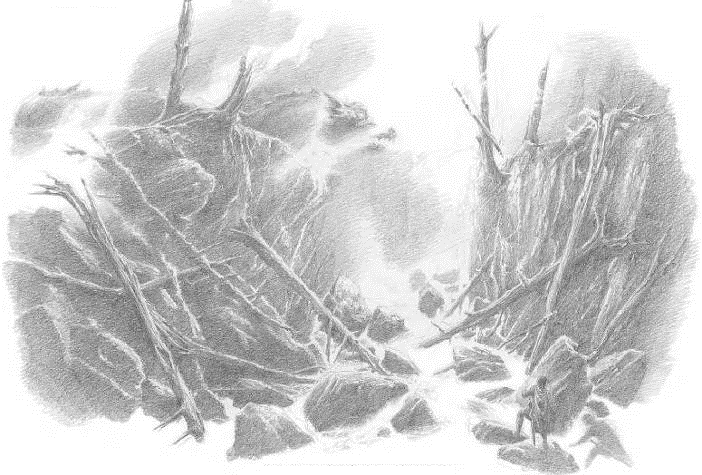

At last, even as full night closed over the land, Turambar and his companions came to Cabed-en-Aras, and they were glad of the great noise of the water; for though it promised peril below, it covered all other sounds. Then Dorlas led them a little aside, southwards, and they climbed down by a cleft to the cliff-foot; but there his heart quailed, for many rocks and great stones lay in the river, and the water ran wild about them, grinding its teeth. ‘This is a sure way to death,’ said Dorlas.

‘It is the only way, to death or to life,’ said Turambar, ‘and delay will not make it seem more hopeful. Therefore follow me!’ And he went on before them, and by skill and hardihood, or by fate, he came across, and in the deep dark he turned to see who came after. A dark form stood beside him. ‘Dorlas?’ he said.

‘No, it is I,’ said Hunthor. ‘Dorlas failed at the crossing, I think. For a man may love war, and yet dread many things. He sits shivering on the shore, I guess; and may shame take him for his words to my kinsman.’

Now Turambar and Hunthor rested a little, but soon the night chilled them, for they were both drenched with water, and they began to seek a way along the stream northwards towards the lodgement of Glaurung. There the chasm grew darker and narrower, and as they felt their way forward they could see a flicker above them as of smouldering fire, and they heard the snarling of the Great Worm in his watchful sleep. Then they groped for a way up, to come nigh under the brink; for in that lay all their hope to come at their enemy beneath his guard. But so foul now was the reek that their heads were dizzy, and they slipped as they clambered, and clung to the tree-stems, and retched, forgetting in their misery all fear save the dread of falling into the teeth of Teiglin.

Then Turambar said to Hunthor: ‘We spend our waning strength to no avail. For till we be sure where the Dragon will pass, it is vain to climb.’

‘But when we know,’ said Hunthor, ‘then there will be no time to seek a way up out of the chasm.’

‘Truly,’ said Turambar. ‘But where all lies on chance, to chance we must trust.’ They halted therefore and waited, and out of the dark ravine they watched a white star far above creep across the faint strip of sky; and then slowly Turambar sank into a dream, in which all his will was given to clinging, though a black tide sucked and gnawed at his limbs.

Suddenly there was a great noise and the walls of the chasm quivered and echoed. Turambar roused himself, and said to Hunthor: ‘He stirs. The hour is upon us. Strike deep, for two must strike now for three!’

And with that Glaurung began his assault upon Brethil; and all passed much as Turambar had hoped. For now the Dragon crawled with slow weight to the edge of the cliff, and he did not turn aside, but made ready to spring over the chasm with his great forelegs and then draw his bulk after. Terror came with him; for he did not begin his passage right above, but a little to the northward, and the watchers from beneath could see the huge shadow of his head against the stars; and his jaws gaped, and he had seven tongues of fire. Then he sent forth a blast, so that all the ravine was filled with a red light, and black shadows flying among the rocks; but the trees before him withered and went up in smoke, and stones crashed down into the river. And thereupon he hurled himself forward, and grappled the further cliff with his mighty claws, and began to heave himself across.

Now there was need to be bold and swift, for though Turambar and Hunthor had escaped the blast, since they were not right in Glaurung’s path, they yet had to come at him, before he passed over, or all their hope failed. Heedless of peril therefore Turambar clambered along the cliff to come beneath him; but there so deadly was the heat and the stench that he tottered and would have fallen if Hunthor, following stoutly behind, had not seized his arm and steadied him.

‘Great heart!’ said Turambar. ‘Happy was the choice that took you for a helper!’ But even as he spoke, a great stone hurtled from above and smote Hunthor on the head, and he fell into the water, and so ended: not the least valiant of the House of Haleth. Then Turambar cried: ‘Alas! It is ill to walk in my shadow! Why did I seek aid? For now you are alone, O Master of Doom, as you should have known it must be. Now conquer alone!’

Then he summoned to him all his will, and all his hatred of the Dragon and his Master, and it seemed to him that suddenly he found a strength of heart and of body that he had not known before; and he climbed the cliff, from stone to stone, and root to root, until he seized at last a slender tree that grew a little beneath the lip of the chasm, and though its top was blasted it still held fast by its roots. And even as he steadied himself in a fork of its boughs, the midmost parts of the Dragon came above him, and swayed down with their weight almost upon his head, ere Glaurung could heave them up. Pale and wrinkled was their underside, and all dank with a grey slime, to which clung all manner of dropping filth; and it stank of death. Then Turambar drew the Black Sword of Beleg and stabbed upwards with all the might of his arm, and of his hate, and the deadly blade, long and greedy, went into the belly even to its hilts.

Then Glaurung, feeling his death-pang, gave forth a scream, whereat all the woods were shaken, and the watchers at Nen Girith were aghast. Turambar reeled as from a blow, and slipped down, and his sword was torn from his grasp, and clave to the belly of the Dragon. For Glaurung in a great spasm bent up all his shuddering bulk and hurled it over the ravine, and there upon the further shore he writhed, screaming, lashing and coiling himself in his agony, until he had broken a great space all about him, and lay there at last in a smoke and a ruin, and was still.

Now Turambar clung to the roots of the tree, stunned and well-nigh overcome. But he strove against himself and drove himself on, and half sliding and half climbing he came down to the river, and dared again the perilous crossing, crawling now on hands and feet, clinging, blinded with spray, until he came over at last, and climbed wearily up the cleft by which they had descended. Thus he came at length to the place of the dying Dragon, and he looked on his stricken enemy without pity, and was glad.

There now Glaurung lay, with jaws agape; but all his fires were burned out, and his evil eyes were closed. He was stretched out in his length, and had rolled upon one side, and the hilts of Gurthang stood in his belly. Then the heart of Turambar rose high within him, and though the Dragon still breathed he would recover his sword, which if he prized it before was now worth to him all the treasure of Nargothrond. True proved the words spoken at its forging that nothing, great or small, should live that once it had bitten.