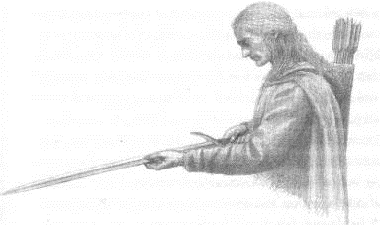

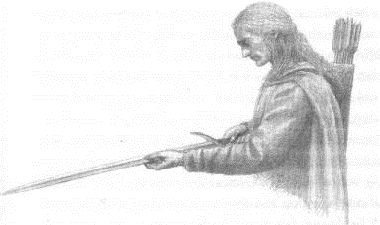

‘I ask then for a sword of worth,’ said Beleg; ‘for the Orcs come now too thick and close for a bow only, and such blade as I have is no match for their armour.’

‘Choose from all that I have,’ said Thingol, ‘save only Aranrúth, my own.’

Then Beleg chose Anglachel; and that was a sword of great fame, and it was so named because it was made of iron that fell from heaven as a blazing star; it would cleave all earth-dolven iron. One other sword only in Middle-earth was like to it. That sword does not enter into this tale, though it was made of the same ore by the same smith; and that smith was Eöl the Dark Elf, who took Aredhel Turgon’s sister to wife. He gave Anglachel to Thingol as fee, which he begrudged, for leave to dwell in Nan Elmoth; but the other sword, Anguirel, its mate, he kept, until it was stolen from him by Maeglin, his son.

But as Thingol turned the hilt of Anglachel towards Beleg, Melian looked at the blade; and she said: ‘There is malice in this sword. The heart of the smith still dwells in it, and that heart was dark. It will not love the hand that it serves; neither will it abide with you long.’

‘Nonetheless I will wield it while I may,’ said Beleg; and thanking the king he took the sword and departed. Far across Beleriand he sought in vain for tidings of Túrin, through many perils; and that winter passed away, and the spring after.

CHAPTER VI

TÚRIN AMONG THE OUTLAWS

Now the tale turns again to Túrin. He, believing himself an outlaw whom the King would pursue, did not return to Beleg on the north-marches of Doriath, but went away westward, and passing secretly out of the Guarded Realm came into the woodlands south of Teiglin. There before the Nirnaeth many men had dwelt in scattered homesteads; they were of Haleth’s folk for the most part, but owned no lord, and they lived both by hunting and husbandry, keeping swine in the mast-lands, and tilling clearings in the forest which were fenced from the wild. But most were now destroyed, or had fled into Brethil, and all that region lay under the fear of Orcs, and of outlaws. For in that time of ruin houseless and desperate men went astray: remnants of battle and defeat, and lands laid waste; and some were men driven into the wild for evil deeds. They hunted and gathered such food as they could; but many took to robbery and became cruel, when hunger or other need drove them. In winter they were most to be feared, like wolves; and Gaurwaith, wolf-men, they were called by those who still defended their homes. Some sixty of these men had joined in one band, wandering in the woods beyond the western marches of Doriath; and they were hated scarcely less than Orcs, for there were among them outcasts hard of heart, bearing a grudge against their own kind.

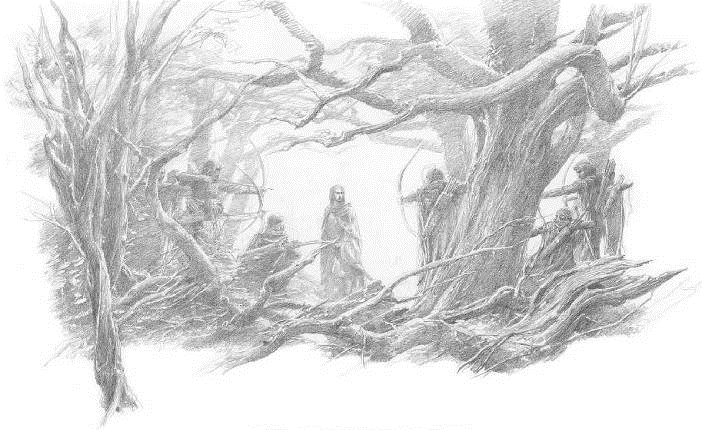

The hardest of heart was one named Andróg, who had been hunted from Dor-lómin for the slaying of a woman; and others also came from that land: old Algund, the oldest of the fellowship, who had fled from the Nirnaeth, and Forweg, as he named himself, a man with fair hair and unsteady glittering eyes, big and bold, but far fallen from the ways of the Edain of the people of Hador. Yet he could still be wise and generous at times; and he was the captain of the fellowship. They had dwindled now to some fifty men, by deaths in hardship or affrays; and they were become wary, and set scouts or a watch about them, whether moving or at rest. Thus they were soon aware of Túrin when he strayed into their haunts. They trailed him, and they drew a ring about him, so that suddenly, as he came out into a glade beside a stream, he found himself within a circle of men with bent bows and drawn swords.

Then Túrin halted, but he showed no fear. ‘Who are you?’ he said. ‘I thought that only Orcs waylaid men; but I see that I am mistaken.’

‘You may rue the mistake,’ said Forweg, ‘for these are our haunts, and my men do not allow other men to walk in them. We take their lives as forfeit, unless they can ransom them.’

Then Túrin laughed grimly: ‘You will get no ransom from me, an outcast and an outlaw. You may search me when I am dead, but it may cost you dearly to prove my words true. Many of you are likely to die first.’

Nonetheless his death seemed near, for many arrows were notched to the string, waiting for the word of the captain, and though Túrin wore elven-mail under his grey tunic and cloak, some would find a deadly mark. None of his enemies stood within reach of a leap with drawn sword. But suddenly Túrin stooped, for he had espied some stones at the stream’s edge before his feet. At that moment an outlaw, angered by his proud words, let fly a shaft aimed at his face; but it passed over him, and he sprang up again like a bowstring released and cast a stone at the bowman with great force and true aim; and he fell to the ground with broken skull.

‘I might be of more service to you alive, in the place of that luckless man,’ said Túrin; and turning to Forweg he said: ‘If you are the captain here, you should not allow your men to shoot without command.’

‘I do not,’ said Forweg; ‘but he has been rebuked swiftly enough. I will take you in his stead, if you will heed my words better.’

‘I will,’ said Túrin, ‘as long as you are captain, and in all that belongs to a captain. But the choice of a new man to a fellowship is not his alone, I judge. All voices should be heard. Are there any here who do not welcome me?’

Then two of the outlaws cried out against him; and one was a friend of the fallen man. Ulrad was his name. ‘A strange way to gain entry to a fellowship,’ he said, ‘the slaying of one of our best men!’

‘Not unchallenged,’ said Túrin. ‘But come then! I will endure you both together, with weapons or with strength alone. Then you shall see if I am fit to replace one of your best men. But if there are bows in this test, I must have one too.’ Then he strode towards them; but Ulrad gave back and would not fight. The other threw down his bow and walked up to meet Túrin. This man was Andróg of Dor-lómin. He stood before Túrin and looked him up and down.

‘Nay,’ he said at length, shaking his head. ‘I am not a chicken-heart, as men know; but I am not your match. There is none here, I think. You may join us, for my part. But there is a strange light in your eyes; you are a dangerous man. What is your name?’

‘Neithan, the Wronged, I call myself,’ said Túrin, and Neithan he was afterwards called by the outlaws; but though he claimed to have suffered injustice (and to any who claimed the like he ever lent too ready an ear), no more would he reveal concerning his life or his home. Yet they saw that he had fallen from high state, and that though he had nothing but his arms, those were made by elven-smiths. He soon won their praise, for he was strong and valiant, and had more skill in the woods than they, and they trusted him, for he was not greedy, and took little thought for himself; but they feared him, because of his sudden angers, which they seldom understood.

To Doriath Túrin could not, or in pride would not, return; to Nargothrond since the fall of Felagund none were admitted. To the lesser folk of Haleth in Brethil he did not deign to go; and to Dor-lómin he did not dare, for it was closely beset, and one man alone could not hope at that time, as he thought, to come through the passes of the Mountains of Shadow. Therefore Túrin abode with the outlaws, since the company of any men made the hardship of the wild more easy to endure; and because he wished to live and could not be ever at strife with them, he did little to restrain their evil deeds. Thus he soon became hardened to a mean and often cruel life, and yet at times pity and disgust would wake in him, and then he was perilous in his anger. In this evil and dangerous way Túrin lived to that year’s end and through the need and hunger of winter, until stirring came and then a fair spring.