"'The night has a thousand eyes,'" Kit said hoarsely, and lifted her head to face the villain. The Baudelaires could tell by her voice that she was reciting the words of someone else. '"And the day but one; yet the light of the bright world dies with the dying sun. The mind has a thousand eyes, and the heart but one: yet the light of a whole life dies when love is done.'"

Count Olaf gave Kit a faint smile. "You're not the only one who can recite the words of our associates," he said, and then gazed out at the sea. The afternoon was nearly over, and soon the island would be covered in darkness. '"Man hands on misery to man,'" the villain said. "'It deepens like a coastal shelf. Get out as early as you can—'" Here he coughed, a ghastly sound, and his hands clutched his chest. "'And don't have any kids yourself,'" he finished, and uttered a short, sharp laugh. Then the villain's story came to an end. Olaf lay back on the sand, far from the treachery of the world, and the children stood on the beach and stared into his face. His eyes shone brightly, and his mouth opened as if he wanted to tell them something, but the Baudelaire orphans never heard Count Olaf say another word.

Kit gave a cry of pain, thick with poisonous fungus, and clutched her heaving belly, and the Baudelaires hurried to help her. They did not even notice when Count Olaf closed his eyes for the last time, and perhaps this is a good time for you to close your eyes, too, not just to avoid reading the end of the Baudelaires' story, but to imagine the beginning of another. It is likely your own eyes were closed when you were born, so that you left the safe place of your mother's womb—or, if you are a seahorse, your father's yolk sac—and joined the treachery of the world without seeing exactly where you were going. You did not yet know the people who were helping you make your way here, or the people who would shelter you as your life began, when you were even smaller and more delicate and demanding than you are now. It seems strange that you would do such a thing, and leave yourself in the care of strangers for so long, only gradually opening your eyes to see what all the fuss was about, and yet this is the way nearly everyone comes into the world. Perhaps if we saw what was ahead of us, and glimpsed the crimes, follies, and misfortunes that would befall us later on, we would all stay in our mother's wombs, and then there would be nobody in the world but a great number of very fat, very irritated women. In any case, this is how all our stories begin, in darkness with our eyes closed, and all our stories end the same way, too, with all of us uttering some last words—or perhaps someone else's—before slipping back into darkness as our series of unfortunate events comes to an end. And in this way, with the journey taken by Kit Snicket's baby, we reach the end of A Series of Unfortunate Events as well. For some time, Kit Snicket's labor was very difficult, and it seemed to the children that things were moving in an aberrant—the word «aberrant» here means "very, very wrong, and causing much grief" — direction. But finally, into the world came a baby girl, just as, I'm very, very sorry to say, her mother, and my sister, slipped away from the world after a long night of suffering—but also a night of joy, as the birth of a baby is always good news, no matter how much bad news the baby will hear later. The sun rose over the coastal shelf, which would not flood again for another year, and the Baudelaire orphans held the baby on the shore and watched as her eyes opened for the first time. Kit Snicket's daughter squinted at the sunrise, and tried to imagine where in the world she was, and of course as she wondered this she began to cry. The girl, named after the Baudelaires' mother, howled and howled, and as her series of unfortunate events began, this history of the Baudelaire orphans ended.

This is not to say, of course, that the Baudelaire orphans died that day. They were far too busy. Although they were still children, the Baudelaires were parents now, and there was quite a lot to do. Violet designed and built the equipment necessary for raising an infant, using the library of detritus stored in the shade of the apple tree. Klaus searched the enormous bookcase for information on child care, and kept careful track of the baby's progress. Sunny herded and milked the wild sheep, to provide nourishment for the baby, and used the whisk Friday had given her to make soft foods as the baby's teeth came in. And all three Baudelaires planted seeds from the bitter apples all over the island, to chase away any traces of the Medusoid Mycelium—even though they remembered it grew best in small, enclosed spaces—so the deadly fungus had no chance to harm the child and so the island would remain as safe as it was on the day they arrived. These chores took all day, and at night, while the baby was learning to sleep, the Baudelaires would sit together in the two large reading chairs and take turns reading out loud from the book their parents had left behind, and sometimes they would flip to the back of the book, and add a few lines to the history themselves. While reading and writing, the siblings found many answers for which they had been looking, although each answer, of course, only brought forth another mystery, as there were many details of the Baudelaires' lives that seemed like a strange, unreadable shape of some great unknown. But this did not concern them as much as you might think. One cannot spend forever sitting and solving the mysteries of one's history, and no matter how much one reads, the whole story can never be told. But it was enough. Reading their parents' words was, under the circumstances, the best for which the Baudelaire orphans could hope.

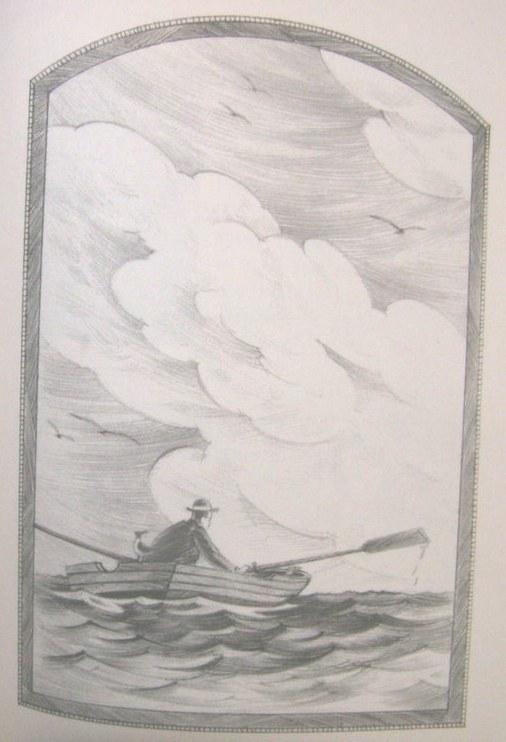

As the night grew later they would drop off to sleep, just as their parents did, in the chairs in the secret space beneath the roots of the bitter apple tree, in the arboretum on an island far, far from the treachery of the world. Several hours later, of course, the baby would wake up and fill the space with confused and hungry cries. The Baudelaires took turns, and while the other two children slept, one Baudelaire would carry the baby, in a sling Violet had designed, out of the arboretum and up to the top of the brae, where they would sit, infant and parent, and have breakfast while staring at the sea. Sometimes they would visit Kit Snicket's grave, where they would lay a few wildflowers, or the grave of Count Olaf, where they would merely stand silent for a few moments. In many ways, the lives of the Baudelaire orphans that year is not unlike my own, now that I have concluded my investigation. Like Violet, like Klaus, and like Sunny, I visit certain graves, and often spend my mornings standing on a brae, staring out at the same sea. It is not the whole story, of course, but it is enough. Under the circumstances, it is the best for which you can hope.

BRETT HELQUIST was born in Ganado, Arizona, grew up in Orem, Utah, and now lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is hopeful that with the publication of the last book in A Series of Unfortunate Events, he'll be able to step outside more often in the daytime, and sleep better at night.

LEMONY SNICKET is the author of all 170 chapters of A Series of Unfortunate Events. He is almost finished.

To My Kind Editor:

TheendofTHISEND can be found at the end of THE END,

With all due respect,

Lemony Snicket