‘I told you, my parents have no money for a lawyer.’

‘I would do it for nothing. Pro bono, as we say.’

His face lightened a little. ‘Would you, sir? If you could help…’

‘I cannot guarantee anything. But if I can, I will.’

‘Thank you.’ He looked at me. ‘I confess I cursed you hard when I learned of your involvement.’

‘Then undo the curse. I have had enough of those recently.’

He smiled. ‘Right readily, if you will aid us.’

‘Well,’ I said, a little embarrassed, ‘I must see how Broderick fares.’

Leacon shook his head as he reached for his keys. ‘Why do folk bring themselves to such a dreadful place as he is in? Is there not enough trouble in the world?’

BRODERICK LOOKED PATHETIC when I entered his cell, lying pale and drawn on his pallet. I stood looking down at him. A candle had been lit against the gathering dusk and it made deep shadows of the premature lines in his young face. He looked up wearily.

‘You have something to drink?’ I asked.

He nodded at a pitcher on the floor. ‘Ay.’

‘I know how you did it, Sir Edward,’ I said quietly. ‘The poison. You took those horrible toadstools from the drainpipe, didn’t you?’

He looked at me for a long moment, then let his eyes fall. ‘ ’Tis all one now,’ he said apathetically. ‘I failed. And now you have moved me there will be no more chances.’

‘Your very being must have cringed when you forced those things into your mouth.’

‘It did. I forced them down with water, held my nose to avoid that smell.’

‘Yes. The smell.’

‘But it did no good. My body voided them.’ His face twisted in a spasm of anger.

‘Listen,’ I said. ‘Why not talk now, give them what they want? They will torture it out of you in the end. There is no virtue in pain. You may be able to negotiate a pardon if you talk; it has been done before.’

He laughed then, a harsh croaking sound. ‘You think I would believe their promises? Robert Aske did, and consider how they served him.’

‘His skeleton fell from the castle tower today. The wind blew it down.’

He smiled slowly. ‘An omen. An omen the Mouldwarp should take note of.’

‘For an educated man, sir, you talk much nonsense.’ I studied him, wondering how many of the answers I sought might lie within his scarred breast – the connection between the Queen’s secret and the conspirators, the contents of that box of papers. But I was forbidden to probe his secrets.

‘If King Henry is the Mouldwarp,’ I asked him suddenly, ‘who then is the rightful King? Some say the Countess of Salisbury’s family.’

He gave me a crooked smile. ‘Some say many things.’

‘Prince Edward is the rightful heir, is he not, the King’s son?’ I paused. ‘And any son Queen Catherine may have after him. There have been rumours she is pregnant.’

‘Have there?’ No flicker in his eyes, only an expression of amused contempt. He laughed coldly. ‘Are you turned interrogator, sir?’

‘I was merely making conversation.’

‘I think you do not merely do anything. But you know what I would like?’

‘What?’

‘To have you with me in that room in the Tower, while they work me. I would have you watch what your good custodianship will bring me too.’

‘You should talk now while your body is still whole.’

‘Go away.’ Broderick’s voice was full of contempt.

I sighed, and knocked on the door for the guard. As I stepped outside, I saw with a sinking heart that Radwinter was there. His eyes looked tired, the skin around them dark. His arrest had told on this man who loved his authority. He stood glaring at Barak, who leaned against the wall, a picture of studied nonchalance.

‘So,’ Radwinter was saying. ‘I hear your master found out how Broderick poisoned himself.’

‘Yes. Broderick did it cleverly.’

‘He will get no further chance. I am restored to my duties.’ He turned to me. ‘Maleverer says I have you to thank for that.’

I shrugged.

‘And you will enjoy the thought I am beholden to you,’ he said bitterly.

‘I do not care,’ I said. ‘I have other matters to think about.’

‘I put you down once,’ Radwinter said. ‘And I will again.’ He shouldered his way past me, almost knocking me into Barak, and called sharply to the soldier to surrender the keys to the prisoner’s cell back to him.

Chapter Twenty-nine

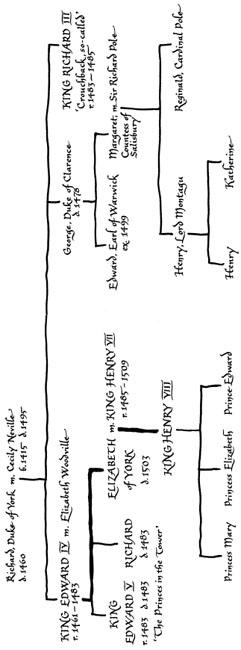

Barak and I sat in my cubicle at the lodging house. Between us on the bed was the piece of paper on which I had copied out again, from memory, the family tree I had found in the box. A lamp set precariously on the bed cast a dim yellow light over the royal names.

‘How can this lead us to who attacked you?’ Barak asked wearily.

‘The answer is always in the detail,’ I said, frowning at it. ‘Bear with me,’ I continued. ‘Now, the Titulus stressed that Richard III was born in England, which gave “more certain knowledge of your birth and filiation”. I have been thinking. I think they were saying between the lines that one of Richard’s brothers was a bastard.’

‘You said yourself the Titulus seemed to be scraping together everything, no matter how shaky, to justify Richard usurping the throne. Where is the evidence?’

I looked at him. ‘Perhaps in that jewel casket?’ I pointed at Cecily Neville’s name at the head of the tree. ‘If one of her children was a bastard that would explain Maleverer’s remark when the papers went missing. “Cecily Neville. It all goes back to her.” ’

Barak stroked his chin. ‘There are two sons beside Richard III.’

‘Yes. George Duke of Clarence who was the father of Margaret of Salisbury, who was executed this year, and Edward IV. The grandfather of the present king.’

‘If the Clarence line were being called into question, that would be useful for the King. He’d want to make it public.’

‘And the conspirators would not. They’d have destroyed any evidence, not kept it hidden and protected. So the allegation must have been aimed at Edward IV, the King’s grandfather. Whom it is said he much resembles.’

Barak looked at me with a horrified expression. ‘If Edward IV was not the son of the Duke of York -’

‘The one through whom the royal bloodline runs – in that case the King’s claim to the throne becomes very weak, far weaker than the Countess of Salisbury’s line. It rests on his father’s claim alone, Henry Tudor.’

‘Who had but little royal blood.’

I pointed to the tree. ‘If I am right, those names marked in bold represent a false line. They are all Edward IV’s descendants.’

‘So who is supposed to have fathered Edward IV?’

‘Jesu knows. Some noble or gentleman about the Yorkist court a hundred years ago.’ I raised my eyebrows. ‘Perhaps someone called Blaybourne.’

Barak whistled, then thought a moment. ‘I never heard of any family of note with that name.’

‘No. But many noble families went down in the Striving between the Roses.’

Barak lowered his voice, though the lodging house was quiet, the clerks all at dinner. ‘These are serious matters. Even to talk of doubting the King’s descent is treason.’

‘If there were evidence, and it were to be released at the same time as evidence about Catherine’s dalliance with Culpeper, that could truly rock the throne. It would turn the majesty of the King into a complete mockery.’ I laughed incredulously.

‘It’s no laughing matter.’ Barak was looking at me narrowly.

‘I know. Only – great Henry, nothing more than the descendant of a cuckoo in the royal nest. If I am right,’ I continued seriously, ‘the information the conspirators had was the most potent brew imaginable, challenging both the King’s own legitimacy and that of any children Catherine Howard may have. I imagine it was planned to reveal it when the rebellion got under way. Only it never did, the conspirators were betrayed before it could start.’