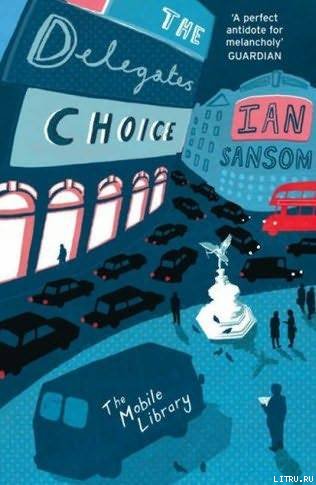

Ian Sansom

The Delegates' Choice aka The Book Stops Here

The third book in the Mobile Library series, 2007

1

'I resign,' said Israel.

'Aye,' said Ted.

'I do,' said Israel.

'Good,' said Ted.

'I've made up my mind. I'm resigning,' said Israel. 'Today.'

'Right you are,' said Ted.

'I've absolutely had enough.'

'Uh-huh.'

'Of the whole thing. This place! The-'

'People,' said Ted.

'Exactly!' said Israel. 'The people! Exactly! The people, they drive me-'

'Crazy,' said Ted.

'Exactly! You took the words right out of my mouth.'

'Aye, well, you might've mentioned it before,' said Ted.

'Well, this is it. I'm up to-'

'High dough,' said Ted.

'What?' said Israel.

'You're up to high dough with it.'

'No,' said Israel. 'No. I don't even know what it means, up to high dough with it. What the hell's that supposed to mean?'

'It's an expression.'

'Ah, right yes. It would be. Anyway, I'm up to…here with it.'

'Good.'

'I'm going to hand in my resignation to Linda.'

'Excellent,' said Ted.

'Before the meeting today.'

'First class,' said Ted.

'Before she has a chance to trick me out of it again.'

'Away you go then.'

'I am so gone already. I am out of here. I tell you, you are not going to see me for dust. I'm moving on.'

'Mmm.'

'I'm going! Look!'

'Ach, well, it's been a pleasure, sure. We're all going to miss you.'

'Yes,' said Israel.

'Good,' said Ted.

'So,' said Israel.

'You've time for a wee cup of coffee at Zelda's first, mind? For auld time's sake?'

'No!' said Israel. 'I need to strike while the-'

'And a wee scone, but?'

Israel looked at his watch.

'Meeting's not till three,' said Ted.

'What day is it?' said Israel.

'Wednesday.'

'What's the scone on Wednesdays?'

'Date and almond,' said Ted, consulting his mental daily-special scone timetable.

Israel huffed. 'All right,' he said. 'But then we need to get there early. I am definitely, definitely resigning.'

They'd had this conversation before, around about midweek, and once a week, for several months now, Israel Armstrong BA (Hons) and Ted Carson-the Starsky and Hutch, the Morse and Lewis, the Thomson and Thompson, the Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the Dante and Virgil, the Cagney and Lacey, the Deleuze and Guattari, the Mork and Mindy of the mobile library world.

Israel had been living in Tumdrum for long enough-more than six months!-to find the routine not just getting to him, but actually having got to him; the self-same rainy days which slowly and silently became weeks and then months, and which seemed gradually to be slowing, and slowing, and slowing, almost but not quite to a complete and utter stop, so that it felt to Israel as though he'd been stuck in Tumdrum on the mobile library not just for months, but for years, indeed for decades almost. He never should have taken the job here in the first place; it was an act of desperation. He felt trapped; stuck; in complete and utter stasis. He felt incapacitated. He felt like he was in a never-ending episode of 24 or a play by Samuel Beckett.

'This is like Krapp's Last Tape,' he told Ted, once they were settled in Zelda's and Minnie was bringing them coffee.

'Is it?' said Ted.

'Are ye being rude about my coffee?' said Minnie.

'No,' said Israel. 'I'm just talking about a play.'

'Ooh!' said Minnie.

'Beckett?' said Israel.

'Beckett?' said Minnie. 'He was a Portora boy, wasn't he?'

'What?' said Israel.

'In Enniskillen there,' said Minnie. 'The school, sure. That's where he went to school, wasn't it?'

'I don't know,' said Israel. 'Samuel Beckett?'

'Sure he did,' said Minnie. 'What was that play he did?'

'Waiting for Godot?' said Israel.

'Was it?' said Minnie. 'It wasn't Educating Rita?'

'Riverdance,' said Ted. 'Most popular Irish show of all time.'

'That's not a play,' said Israel wearily.

'Aye, you're a theatre critic now, are ye?'

'Och,' said Minnie. 'And who was the other fella?'

'What?' said Israel.

'That went to school there, at Portora?'

'No, you've got me,' said Israel. 'No idea.'

'Ach, sure ye know. The homosexualist.'

'You've lost me, Minnie, sorry.'

'Wrote the plays. "A handbag!" That one.'

'Oscar Wilde?'

'He's yer man!' said Minnie. 'He was another Portora boy, wasn't he, Ted?'

Ted was busy emptying the third of his traditional three sachets of sugar into his coffee. 'Aye.'

'Zelda's nephew went there,' said Minnie. 'The one in Fermanagh there.'

'Right,' said Israel. 'Anyway…'

'I'll check with her.'

'Fine,' said Israel.

'And your scones are just coming,' said Minnie.

'That's grand,' said Ted, producing a pack of cigarettes.

'Uh-uh,' said Minnie, wagging her finger. 'We've gone no smoking.'

'Ye have not?' said Ted.

'We have indeed.'

'Since when?'

'The weekend, just.'

'Ach,' said Ted. 'That's the political correctness.'

'I know,' said Minnie. 'It's what people want though, these days.'

'You'll lose custom, but.'

'Aye.'

'Nanny state,' said Ted, obediently putting away his cigarettes and lighter.

'Smoking kills,' said Israel.

'Aye, and so do a lot of other things,' said Ted darkly.

'It is a shame, really,' said Minnie. 'Sure, everybody used to smoke.'

Israel stared at the yellowing walls of the café as Ted and Minnie reminisced about the great smokers of the past: Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Bette Davis, Winston Churchill, Fidel Castro.

'Beagles,' said Israel.

'What?' said Minnie.

'And Sherlock Holmes,' added Israel.

'Aye,' said Ted.

'Was he not a druggie?' said Minnie.

'Sam Spade,' said Israel.

'Never heard of him,' said Minnie.

Sometimes Israel wished he was a gentleman detective, far away from here, with a cocaine and morphine habit, and a slightly less intelligent confidant to admire his genius. Or, like Sam Spade, the blond Satan, pounding the hard streets of San Francisco, entangling with knock-out redheads and outwitting the Fat Man. Instead, here he was in Zelda's, listening to Ted and Minnie and looking up at old Christian Aid and Trócaire posters, and the dog-eared notices for the Citizens Advice Bureau, and the wilting pot plants, and the lone long-broken computer in the corner with the Blu-Tacked sign above it proclaiming the café Tumdrum's Internet hot spot, THE FIRST AND STILL THE BEST, and the big laminated sign over by the door featuring a man sitting slumped with his head in his hands, advertising the Samaritans: 'Suicidal? Depressed?'

Well, actually…

He sipped at his coffee and took a couple of Nurofen. The coffee was as bad as ever. All coffee in Tumdrum came weak, and milky, and lukewarm, as though having recently passed through someone else or a cow. Maybe he should take up smoking, late in life, as an act of flamboyance and rebellion: a smoke was a smoke, after all, but with a coffee you couldn't always be sure. The coffee in Tumdrum was more like slurry run-off. He missed proper coffee, Israel-a nice espresso at Bar Italia just off Old Compton Street, that was one of the things he missed about London, and the coffee at Grodzinski's, round the corner from his mum's. He missed his friends, also, of course; and his books; and the cinema; a nice slice of lemon drizzle cake in the café at the Curzon Soho; and the theatre; and the galleries; and the restaurants; it was the little things; nothing much; just all the thriving cultural activities of one of the world's great capital cities.