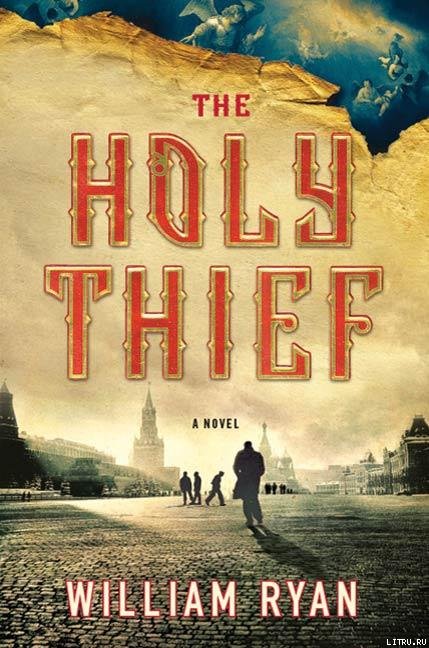

William Ryan

The Holy Thief

© 2010

To Joanne

In the still air of the sacristy the only sounds were the slow dripping of her blood onto the marble floor and the faint whisper of her breathing. In, out, in, out-then a lengthy pause before the ragged rhythm began again. She was nearly gone.

It had been a messy business. She’d bled a lot, which was to be expected, although it still made him uncomfortable. But what else could he have done? When there wasn’t time to unpick a person mentally, to grind them down-then you had to use pain and terror. Even if it wasn’t necessarily the most professional, or even the most effective, approach. He’d hoped he could shock her into submission, but, in the end, she’d simply outlasted the time he’d had available. It was a shame. Sometimes he only had to put on one of the gauntlets, slowly, perhaps making a fist so that the stiff leather creaked as it stretched across his knuckles, and that would be enough. They’d start gabbling so fast the only problem was having a typist quick enough to keep up with them. He preferred it that way, of course-they were more pleasant, the straightforward interrogations. But for every gabbling goose there was a rock-and the girl had been of the granite variety.

Everything he’d tried had failed. If he’d had more time, maybe he would have succeeded, but he’d only had these two hours. Two hours for a mind like that? Strong-closed tight like a metal box. It wasn’t enough. They wouldn’t be happy, but what did they expect? He’d warned them after all. If he could have softened her up first-no sleep for a few days, a hot cell, a freezing cell, complete darkness, complete silence. Well, then he could have made some progress. With time and the right tools he could have found out things from her she didn’t even know she knew herself. Instead, he’d had nothing to work with, really-just his leather apron, his gauntlets and a couple of hours in the back of some church.

He didn’t like that either. It was sanctioned, of course-at the highest levels they’d said. But even so. If he was disturbed, the situation would be difficult to explain-particularly now, with her blood pooling underneath the altar. Anyone coming in off the street would think he was a madman.

Her breathing slowed again and he looked down at his evening’s work. Her eyes, two huge black pupils surrounded by a narrow halo of gold-flecked almond, had accepted what was happening to her, and the light was slowly dimming in them. He looked for fear, but there was none. It often happened that way; at a certain point they went past fear, and even pain, and it was the Devil’s own job to bring them back. He leaned in closer, wondering if one of these days he might catch a glimpse of the next world through eyes such as hers. He searched, but there was nothing-her gaze was fixed on the ceiling above them and that was all. There was a painting up there of the saints in heaven, and maybe her gaze was fixed on that. He moved his head forward to block her view, but her eyes just looked straight through him.

At least when he was this close to her the stench was less oppressive. He could still detect the damp syrupy smell of her blood, but there was also the scent of soap and wet hair and something about the mixture that reminded him of a child. He remembered it from when his son had been newly born-a warm, happy aroma that had filled his heart. He wondered where she’d found the soap-there was little in the ordinary shops this year. You might get some in a closed shop or a currency shop, but even then it wasn’t always available. He puzzled about the soap for a moment, and then remembered-she’d probably brought it with her. American soap. Of course, that made sense. Capitalist soap.

Still, he was surprised to feel something approaching sympathy for the girl. Tears had washed away some of the blood from her cheeks and she looked quite beautiful, her delicate nostrils dilating minutely as she breathed. He held his own breath for a moment, irrationally concerned that exhaling might fog those bottomless eyes of hers. He swallowed and then put the emotion aside. This was no time for self-indulgence. From the very first day, they’d drummed into him the dangers of misplaced pity, and the mistakes it caused. He’d have to revive her, make one last effort.

He put a finger to her neck: the pulse was still there, but barely detectable. He stood up and reached for the smelling salts. There was blood on the bottle-he’d used it twice already-and a part of him wanted to let her go in peace, but he had his instructions, and even if the likelihood she’d tell him anything was remote, there was still a chance. He uncorked the bottle and pulled her head toward him. She tried to twist away from his hand, but the movement was weak.

There seemed to be no change at first, but, when he turned to put the bottle back in his bag, her eyes followed him and, what was more, she seemed to be trying to speak. He picked up his knife and ran the blade down along her cheek, cutting skin and material together in his hurry to remove the gag. She coughed as he pulled the cloth away-blood had smeared her white teeth and he noted how thin and gray her lips were. Her breathing had quickened with the effort, but now she calmed a little, swallowed and focused on him. He leaned slightly to the side to hear what she might say, without breaking eye contact, and she whispered something indistinct. He shook his head and leaned further forward, waiting for her to try again. She took a deep breath, her eyes never leaving his.

“I forgive you,” she said, and it was almost as if he amused her.

CHAPTER ONE

It was later than usual when Captain Alexei Dmitriyevich Korolev climbed the steps in front of Number 38 Petrovka Street, headquarters of the Moscow Militia’s Criminal Investigation Division. The morning had started badly, wasn’t getting any better and he still hadn’t shaken off the pounding vodka headache from the night before, so it was with weary resignation rather than Stakhanovite enthusiasm that he pushed open one of the heavy oak doors. It took his eyes, dazzled from walking into the flat morning sun, a moment to adjust to the relative darkness of the vestibule, and it didn’t help that thick clouds of masonry dust swirled around where he’d expected to find uniformed duty officers and bustling activity. He stopped for a moment, confused, wondering what on earth was going on and looking for a source of all the dust and debris. He was rewarded with a blurred movement that shifted the billowing haze on the landing-up where the statue of former General Commissar of State Security, Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda, stood. The movement was cut short by the crash of something very solid hitting what he strongly suspected was the plinth on which the commissar’s statue rested. The noise, amplified by the marble floor and walls of the atrium, hit Korolev like a slap.

Korolev moved forward warily and began to climb the staircase toward the landing where the statue stood, fragments crunching underfoot. The commissar, swathed in blankets, was a muffled shape around the base of which four workers, stripped to the waist, toiled with crowbars, hammers and a mechanical drill which now thudded into action. Their objective appeared to be the statue’s removal, but the plinth appeared to have other ideas. As Korolev approached, a worker looked up at him and smiled, white teeth cracking open a face plastered with gray dust.