Part Three

EDMOND DOYA 2610 A.D.

SOMETIMES I dreamed about Icehenge, and walked in awe across the old crater bed, among those tall white towers. Quite often in the dreams I had become a crew member of the Persephone, on that first expedition to Pluto in 2547. I landed with the rest of them on a plain of crater-pocked, shattered black basalt, down near the old mechanical probes. And I was there, in the bridge with Commodore Ehrung and the rest of her officers, when the call came in from Dr. Cereson, who was out in an LV locating the magnetic poles. His voice was high, it cracked with excitement that sounded like fear, and radio hiss sputtered in his pauses:

“I’m landing at the geographical pole — you’d better send a party up here fast… there’s a… a structure up here…”

Then I would dream I was in the LV that sped north to the pole, crowded in with Ehrung and the other officers, sharing in the tense silence. Underneath us the surface of Pluto flashed by, black and obscure, ringed by crater upon crater. I remember thinking in the dreams that the constant radio hiss was the sound of the planet. Then — just like in the films the Persephone brought back, you could say I dreamed myself into the films — we could see forward to the dark horizon. Low in the sky hung the crescent of Charon, Pluto’s moon, and below it — white dots. A cluster of white towers. “Let’s go down,” said Ehrung quietly. A circle of white beams, standing on their ends, pointing up at the thick blanket of stars.

Then we were all outside, in suits, stumbling toward the structure. The sun was a bright dot just above the towers, casting a clear pale light over the plain. Shadows of the towers stretched over the ground we crossed; members of the group stepped into the shadow of a beam, disappeared, reappeared in the next slot of sunlight. The regolith we walked over was a dusty black gravel. Everyone left big footprints.

We walked between two of the beams — they dwarfed us — and were in the huge irregular circle that the beams made. It looked as if there were a hundred of them, each a different size. “Ice,” said a voice on the intercom. “They look like ice.” No one replied. And here the dreams would always become confused. Everything happened out of order, or more or less at once; voices chattered in the earphones, and my vision bumped and jiggled, just as the film from that first hand-held camera had done. They found poor Seth Cereson, who had pressed himself against one of the largest beams, faceplate directly on the ice, in a shadow so that he was barely visible. He was in shock as they led him back to the LVs, and kept repeating in a small voice that there was something moving inside the beam. That frightened everyone a bit. Several people walked over and inspected a fallen beam, which had shattered into hundreds of pieces when it hit the ground. Others looked at the edges of the three triangular towers, which were nearly transparent. From a vantage point on top of one of the beams I looked down and saw the tiny silver figures scurrying from beam to beam, standing in the center of the circle looking about, clambering onto the fallen one…

Then there was a shout that cut through the other voices. “Look here! Look here!”

“Quietly, quietly,” said Ehrung. “Who’s speaking?”

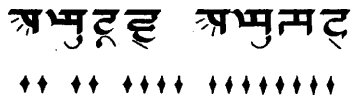

“Over here.” One of the figures waved his arms and pointed at the beam before him. Ehrung walked swiftly toward him, and the rest of us followed. We grouped behind her and stared up at the tower of ice. In the smooth, slightly translucent white surface there were marks engraved:

For a long time Ehrung stood and stared at them, and the crew behind her stared too. And in the dream, I knew that they were two Sanskrit words, carved in the Narangi alphabet: abhy-ud, and aby-ut-sad. And I knew what they meant: to move, to push farther out; to cause to set out towards.

Another time, caught in that half sleep just before waking, when you know you want to get up but something keeps you from it, I dreamed I was on another expedition to Icehenge, a later one determined to clear up once and for all the controversy surrounding its origins. And then I woke up. Usually it is one of the few moments of grace in our lives, to wake up apprehensive or depressed about something, and then realize that the something was part of a dream, and nothing to worry about. But not this time. The dream was true. The year was 2610, and we were on our way to Pluto.

There were seventy-nine people on board Snowflake: twenty-four crew, sixteen reporters, and thirty-nine scientists and technicians. The expedition was being sponsored by the Waystation Institute for Higher Learning, but essentially it was my doing. I groaned at the thought and rolled out of bed.

My refrigerator was empty, so after I splashed water on my face, I went out into the corridor, it had rough wood walls, set at slightly irregular angles; the floor was a lumpy moss that did surprisingly well underfoot.

As I passed by Jones’s chamber the door opened and Jones walked out. “Doya!” he said, looking down at me. “You’re out! I’ve missed you in the lounge.”

“Yes,” I said, “I’ve been working too much, I’m ready for a party.”

“I understand Dr. Brinston wants to talk to you,” he said, brushing down his tangled auburn hair with his fingers. “You going to breakfast?”

I nodded and we started down the corridor together. “Why does Brinston want to talk to me?”

“He wants to organize a series of colloquia on Icehenge, one given by each of us.”

“Oh, man. And he wants me to join it?” Brinston was the chief archaeologist, and as such probably the most important member of our expedition, even though Dr. Lhotse of the Institute was our nominal leader. It was a fact Brinston was all too aware of. He was a pain in the ass — a gregarious Terran (if that isn’t being redundant), and an overbearing academic hack. Although not truly a hack — he did good work.

We turned a corner, onto the main passageway to the dining commons. Jones was grinning at me. “Apparently he believes that it would be essential to have your participation in the series, you know, given your historical importance and all.”

“Give me a break.”

In the white hallway just outside the commons there was a large blue bulletin screen in one of the walls. We stopped before it. There was a console under it for typing messages onto the board. The new question, put up just recently, was the big one, the one that was sending us out here: “Who put up Icehenge?” in bold orange letters.

But the answers, naturally, were jokes. In red script near the center of the board, was “GOD.” In yellow type, “Remnants of a Crystallized Ice Meteorite.” In a corner, in long green letters: “Nederland.” Under that someone had typed, “No, Some Other Alien.” I laughed at that. There were several more solutions (I liked especially “Pluto Is a Message Planet From Another Galaxy”), most of which had first been put forth in the year after the discovery, before Nederland published the results of his work on Mars.

Jones stepped up to the console. “Here’s my new one,” he said. “Let’s see, yellow Gothic should be right: ‘Icehenge put there by prehistoric civilization’ ” — this was Jones’s basic contention, that humans were of extraterrestrial origin, and had had a space technology in their earliest days — “’But the inscription carved on it by the Davydov starship.’”