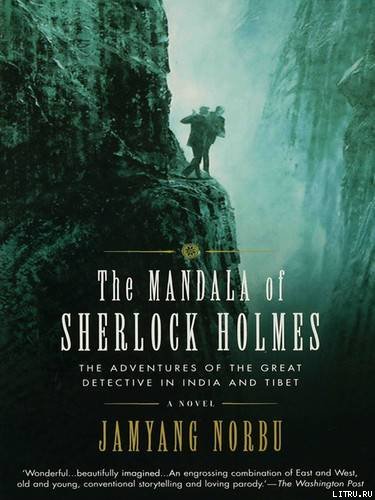

Jamyang Norbu

The Mandala of Sherlock Holmes

© 1997

Based on the reminiscences of

Hurree Chunder Mookerjee

C.I.E., F.R.G.S., Rai Bahadur

Fellow of the Royal Society, London

Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, London and recipient of Founder's Medal

Corresponding Member of the Imperial Archaeological Society of

St. Petersburg

Associate Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal,

Calcutta

Life Member of Brahmo Somaj, Calcutta

I travelled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhassa and spending some days with the head Lama. You may have read of the remarkable explorations of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend.

Sherlock Holmes

The Empty House

Is not all life pathetic and futile?… We reach. We grasp. And what is left in our hands at the end? A shadow. Or worse than a shadow – misery.

Sherlock Holmes

The Retired Colourman

The Mandala (Tib.: dkyi-‘khor) is a sacred circle surrounded by light rays or the place purified of all transitory or dualist ideas. It is experienced as the infinitely wide and pure sphere of consciousness in which deities spontaneously manifest themselves… Mandalas have to be seen as inward pictures of a whole (integral) world; they are creative primal symbols of cosmic evolution and involution, emerging and passing in accordance with the same laws. From this perspective, it is but a short step to conceiving of the Mandala as a creative principle in relation to the external world, the macrocosmos – thus making it the centre of all existence.

Detlef Ingo Lauf

Tibetan Sacred Art

From time to time, God causes men to be born – and thou art one of them – who have a lust to go abroad at the risk of their lives and discover news – today of far-off things, tomorrow of some hidden mountain, and the next day of some near-by men who have done a foolishness against the State. These souls are very few; and of these few, no more than ten are of the best. Among these ten I count the Babu.

Rudyard Kipling

Kim

When everyone is dead the Great Game is finished. Not before. Listen to me till the end.

Rudyard Kipling

Kim

Preface

Too many of Dr John Watson's unpublished manuscripts (usually discovered in 'a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch box' somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox & Company, at Charing Cross) have come to light in recent years, for a longsuffering reading public not to greet the discovery of yet another Sherlock Holmes story with suspicion, if not outright incredulity. I must, therefore, beg the reader's indulgence and request him to defer judgement till he has gone through this brief explanation of how, mainly due to the peculiar circumstance of my birth, I came into the possession of this strange but true account of the two most important but unrecorded years of Sherlock Holmes's life.

I was born in the city of Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, in 1944, the year of the Wood-Monkey, into a well-to-do merchant family. My father was an astute man, and having travelled far and wide – to Mongolia, Turkestan, Nepal and China – on business matters, was more aware than most other Tibetans of the fragility of our happy yet backward country. Realising the advantages of a modern education, he had me admitted to a Jesuit school at the hill station of Darjeeling in British India.

My life at St Joseph's College was, at first, a lonely one, but on learning the English language I soon made many friends, and best of all, discovered books. Like generations of other schoolboys I read the works of G. A. Henty, John Buchan, Rider-Haggard and W. E. Johns, and thoroughly enjoyed them. Yet nothing could quite equal the tremendous thrill of reading Kipling or Conan Doyle – especially the latter's Sherlock Holmes adventures. For a boy from Tibet there were details in those stories that did at first cause some bewilderment. I went around for some time thinking that a gasogene' was a kind of primus stove and that a 'Penang lawyer' was, well, a lawyer from Penang – but these were trifling obstacles and never really got in the way of my fundamental appreciation of the stories.

Of all the Sherlock Holmes stories the one that fascinated me most was the adventure of The Empty House. In this remarkable tale Sherlock Holmes reveals to Dr Watson that for two years, while the world thought that the great detective had perished in the Reichenbach Falls, he had actually been travelling in my country, Tibet! Holmes is vexingly terse, and two sentences are all we have had till now of his historic journey:

I travelled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhassa, and spending some days with the head Lama. You may have read of the remarkable exploration of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend.

When I returned to Lhasa on my three-month winter vacation, I did try and enquire about the Norwegian explorer who had entered our country fifty years ago. A maternal granduncle thought he remembered seeing such a foreigner at Shigatse, but was confusing him with Sven Hedin, the famous Swedish geographer and explorer. Anyway the grown-ups had far more serious problems to consider than a schoolboy's enquiries about a European traveller from yesteryear.

At the time, our country was occupied by Communist troops. They had invaded Tibet in 1950, and after defeating the small Tibetan army, had marched into Lhasa. Initially the Chinese had not been openly repressive and had only gradually implemented their brutal and extreme programmes to eradicate traditional society. The warlike Khampa and Amdowa tribesmen of Eastern Tibet staged violent uprisings that quickly spread throughout the country. The Chinese occupation army retaliated with savage reprisals in which tens of thousands of people were massacred, and many more thousands imprisoned or forced to flee their homes.

In March 1959, the people of Lhasa, fearing for the life of their ruler, the young Dalai Lama, rose up against the Chinese. Fierce fighting broke out in the city but superior Chinese forces overwhelmed the Tibetans, inflicting heavy casualties and damaging many buildings. I was in my final year at school in Darjeeling when the great revolt broke out in Lhasa. The news made me sick with worry about the fate of my parents and relatives. There was little information from Lhasa, and what little there was was vague and none too reassuring. But an anxious month later, All India Radio broadcast the happy news that the Dalai Lama and his entourage, along with many other refugees, had managed to escape from war-torn Tibet and arrived safely at the Indian border. Two days later I received a letter with a Gangtok postmark. It was from my father. He and the other members of my family were safe at the capital of the small Himalayan kingdom of Sikkim.

From the beginning my father had not been taken in by Chinese assurances and display of goodwill, and had quiedy gone about making preparations to escape. He managed to secretly transfer most of his assets to Darjeeling and Sikkim, so that we were now in a very fortunate situation compared to most other Tibetan refugees, who were virtually paupers.