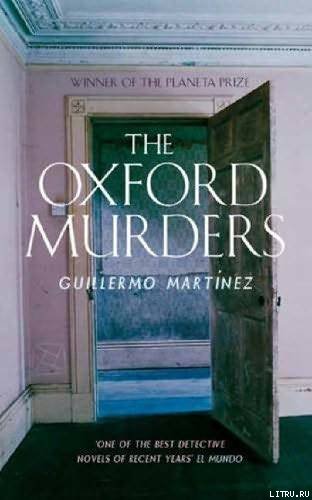

Guillermo Martinez

The Oxford Murders

© 2005

One

Now that the years have passed and everything’s been forgotten, and now that I’ve received a terse e-mail from Scotland with the sad news of Seldom’s death, I feel I can break my silence (which he never asked for anyway) and tell the truth about events that reached the British papers in the summer of ‘93 with macabre and sensationalist headlines, but to which Seldom and I always referred-perhaps due to the mathematical connotation-simply as the series, or the Oxford Series. Indeed, the deaths all occurred in Oxfordshire, at the beginning of my stay in England, and I had the dubious privilege of seeing the first at close range.

I was twenty-two, an age at which almost anything can still be excused. I’d just graduated from the University of Buenos Aires with a thesis in algebraic topology and was travelling to Oxford on a year’s scholarship, secretly intending to move over to logic, or at least attend the famous seminars run by Angus Maclntyre. My supervisor, Dr Emily Bronson, had made all the preparations for my arrival with meticulous care. She was a professor and fellow of St Anne’s, but in the e-mails we exchanged before my trip she suggested that, instead of staying in the rather uncomfortable college accommodation, I might prefer-grant money allowing-to rent a room with its own bathroom, kitchen and entrance in the house of a Mrs Eagleton, a delightful and discreet lady, she said, the widow of her former professor. I did my sums, as always a little optimistically, and sent off a cheque for advance payment of the first month’s rent, the landlady’s only requirement.

A fortnight later I was flying over the Atlantic in the incredulous state which overcomes me when I travel: it always seems much more likely, and more economical as a hypothesis-Ockham’s Razor, Seldom would have said-that a last-minute accident will send me back to where I started, or to the bottom of the sea, than that an entire country and the immense machinery involved in starting a new life will appear eventually like an outstretched hand down below. And yet, exactly on time, the plane cut calmly through the layer of cloud, and the green hills of England appeared, undeniably true to life, in a light that had suddenly faded, or perhaps I should say deteriorated, because that was my impression: that, as the plane went down, the light was becoming increasingly tenuous, as if it were weakening and languishing, having passed through a filter.

My supervisor had instructed me to take the bus from Heathrow straight to Oxford and apologised several times for not being able to meet me when I arrived as she’d be in London all week at an algebra conference. Far from bothering me, this seemed ideal. I’d have a few days to wander around town and get my bearings, before my academic duties began. I didn’t have much luggage, so when the bus arrived at the station I carried my bags across the square to get a taxi. It was the beginning of April but I was glad I’d kept my coat on: there was an icy, cutting wind, and the pallid sun wasn’t much help. Even so, I noticed that almost everyone at the fair occupying the square, as well as the Pakistani driver who opened his taxi door for me, was in short sleeves. I gave him Mrs Eagleton’s address and as we drove off I asked if he wasn’t cold. “Oh no, it’s spring,” he said, waving towards the feeble sun as if this were irrefutable proof.

The black cab advanced sedately towards the main street. As it turned left, I saw, on either side, through half-open wooden gates and iron railings, neat college gardens with immaculate, bright-green lawns. We passed a small graveyard beside a church, with tombstones covered in moss. The taxi went a little way along Banbury Road before turning into Cunliffe Close, the address I had written down. The road now wound through an imposing park. Large, serenely elegant stone houses appeared behind privet hedges, reminding me of Victorian novels with afternoon tea, games of croquet and strolls through the gardens. We checked the house numbers along the road but, judging by the amount of the cheque I’d sent, I couldn’t believe that the house I was looking for was one of these. At last, at the end of the road, we came to a row of identical little houses, much more modest but still pleasant, with rectangular wooden balconies and a summery look to them. Mrs Eagleton’s was the first house. I unloaded my bags, climbed the small flight of steps at the entrance and rang the bell.

From the dates of her PhD thesis and early published work, I guessed that Emily Bronson must be about fifty-five, so I wondered how old the widow of her former professor might be. The door opened and I saw the angular face and dark-blue eyes of a tall, slim girl not much older than me. She held out her hand, smiling. We stared at each other in pleasant surprise, but then she seemed to draw back cautiously as she freed her hand, which I may have held a little too long. She told me her name, Beth, and tried to repeat mine, not entirely successfully, before showing me into a very cosy sitting room with a rug patterned with red and grey lozenges.

Mrs Eagleton sat in a floral armchair and held out her hand, smiling welcomingly. The old lady had twinkling eyes and a lively manner, and her white hair was carefully arranged in a bun. As I crossed the room, I noticed that there was a wheelchair folded up and leaning against the back of her armchair. A tartan blanket was laid over her legs. We shook hands and I felt her frail, slightly tremulous fingers. She held my hand warmly for a moment, patting it with her other hand, and asked about my journey and whether this was my first visit to England.

“We weren’t expecting someone so young, were we, Beth?” she said with surprise.

Beth, standing by the door, smiled but said nothing. She took a key from a hook on the wall and, after I’d answered a few more questions, she suggested gently:

“Don’t you think, grandmother, that we should show him to his room now? He must be terribly tired.”

“Of course,” said Mrs Eagleton. “Beth will explain everything. And if you don’t have anything else planned this evening, we’d be delighted if you’d join us for dinner.”

I followed Beth out of the house and down a little flight of steps to the basement. She stooped slightly as she opened the small front door and showed me into a large, tidy room. Though below ground level, it received quite a lot of light from two windows, very high up by the ceiling. Beth began explaining all the little details as she walked about the room, opening drawers and showing me cupboards, cutlery and towels, in a kind of recitation that she must have repeated many times. I checked out the bed and the shower, but mainly I looked at her. Her skin was dry, tanned, taut, as if she spent a lot of time outdoors, and although it made her look healthy, it also made her look in danger of ageing early.

At first I’d thought she was in her early twenties but now, seeing her in different light, I realised that she must be nearer twenty-seven or twenty-eight. Her eyes were particularly intriguing: they were a very beautiful deep blue, but they seemed more still than the rest of her features, as if reluctant to express emotion. She was wearing a long, loose peasant dress with a round neck, which didn’t give much away about her body other than that she was thin, although looking more closely I saw hints that, luckily, she wasn’t thin all over. From the back, especially, she looked very huggable. Like all tall girls, there was something slightly vulnerable about her. When our eyes met again she asked me-without irony, I think-if there was anything else I wanted to check out. I looked away, embarrassed, and quickly answered that everything seemed fine. Before she left I asked, taking much too long to get to the point, whether I really should consider myself invited to dinner. She laughed and said that of course I should, and that they’d expect me at six-thirty.