John Manning

The Killing Room

© 2010

Prologue

Jeanette Young didn’t believe what her Uncle Howard had told her. It was all utter nonsense. If her brothers and cousins really believed such things, then they were fools. This wasn’t the Middle Ages, after all. This was 1970. And no matter what anyone tried to tell her, Jeanette refused to accept the idea that her father-her wise, beloved, dearly missed father-had ever considered such outlandish tales to be true.

“But perhaps,” Uncle Howard had said softly, taking Jeanette’s hand, “you can now better understand the manner of your father’s death.”

That had been an hour ago. Now Jeanette was alone, pondering everything her uncle had said. She threw open the window and breathed in the crisp night air. As always, the sound of waves crashing against the rocks far below the cliff soothed her. They always had, ever since she was a young girl and her father would bring her to this house to visit Uncle Howard. Those were happy days. The house had been filled with laughter. How could they all have been living with a secret like the one Uncle Howard had just revealed to her?

Uncle Howard and the others-her Aunt Margaret, her brothers, her cousins-were hoping that she would come around and accept their stories as true. That’s why they had left her alone, so she could think. But even as she reflected on all she’d been told tonight, Jeanette’s ideas didn’t change. They simply hardened.

“It’s beyond ridiculous,” she said out loud, her voice echoing in the empty parlor. “And I’ll prove it by spending the night in the room where my father died.”

It was the last weekend of September. Only a few tenacious leaves still clung to the branches of the trees. Just as the family had done every ten years for the last half century, the Young clan had gathered at Uncle Howard’s great old house on the coast of Maine. As a child and teenager, Jeanette had looked forward to the family reunions. She had enjoyed playing on the grassy lawn that stretched along the cliffs overlooking the Atlantic. With glee she had cracked the lobster claws served up by the cooks, dipping the succulent meat into the bowls of warm butter they brought out from the kitchen. Jeanette had never known about the meeting that took place on Saturday night at midnight in the parlor. Only at this gathering had she learned of that. At twenty-five, Jeanette was finally old enough to be initiated into the family secret, and to take her place in the lottery.

At the stroke of midnight, they had all gathered in the parlor. Jeanette stood beside Uncle Howard, Aunt Margaret, her brothers, and her cousins. The crackling flames in the fireplace filled the room with the fragrance of oak. Aunt Margaret had written their names on slips of paper and placed them into a wooden box. Uncle Howard, being the patriarch, reached in to select one. Everyone had watched in silence. When he pulled out Jeanette’s name, the old man’s face had gone white. “No,” he said, his voice breaking. “She’s too young.”

Her eldest brother Martin had echoed the objection. “I’ll do it in her place,” he offered, prompting a little cry from his wife, no doubt thinking of their two small children asleep in rooms upstairs.

“It would only make it worse,” Aunt Margaret said. She claimed to know such things, since she and Uncle Howard were the only ones left who remembered how the madness had begun some forty years earlier. “My father tried to shield my brother Jacob when his name was drawn,” she told the family. “Jacob had just turned sixteen. Father insisted he was too young, and so he spent the night in the room in Jacob’s place. But it was supposed to have been Jacob, since it was his name that had been chosen.” She shuddered. “And we all know how that night turned out.”

Everyone had nodded except for Jeanette. “No,” she said, “I don’t know how that night turned out.” They had told her about the lottery and revealed the secret in the basement, but they hadn’t told her this. She looked from face to face and said, “Tell me what happened that night.”

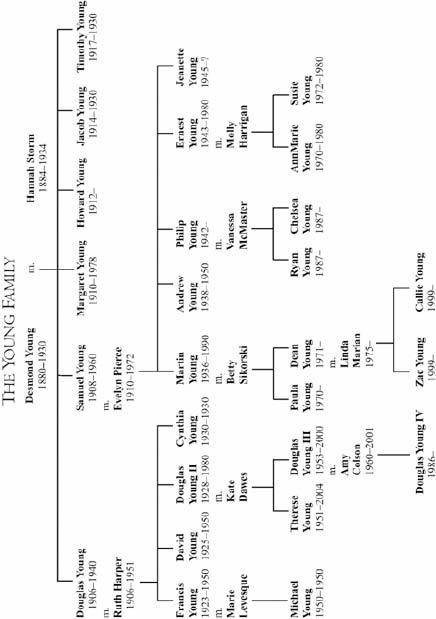

Aunt Margaret’s eyes were cold. “If you go down to the cemetery,” she said, “you’ll see there wasn’t just one death in the family that year. There was a slaughter. My father was killed. And Jacob, too, even though he never stepped a foot in that room. And my youngest brother Timothy as well, and even my newborn niece Cynthia. All as a lesson for us never again to meddle with the lottery.”

That’s when Jeanette had asked to be alone. In her hands she held a family tree that had been compiled by Aunt Margaret. She saw the death dates of all of those who had died that first night in 1930, and then the series of deaths that occurred in ten-year intervals thereafter. Her uncle Douglas in 1940. Her cousin David in 1950. And then, ten years later, her father. She looked down at his name. Samuel Young. Died 1960.

Jeanette remembered the morning they all started out for Uncle Howard’s house. She was fifteen, thrilled to be heading up the coast from their house outside Boston. She loved her uncle and thought his house was fascinating, with all its many rooms and marble staircases and outstanding views of the cliffs and the ocean. She had been excited to see her cousins. But her parents and her two older brothers were glum. At the family picnic that Saturday, the children had turned somersaults on the lawn and splashed in the surf at the bottom of the cliff, but the adults had been somber, talking quietly among themselves. That night, Jeanette was awakened after midnight by her father, slipping into her room to hug her tight. “I love you, Jen,” he’d whispered as he kissed her forehead. In the morning she learned he’d died of a heart attack in his sleep.

Now her uncle was telling her a very different story of her father’s death.

After Dad’s death, Mom had turned to drink. She had chosen not to accompany Jeanette and her brothers to Uncle Howard’s this year. Drunk, almost incoherent, she’d clung to Jeanette when she said good-bye. If the stories she’d been told were true, Jeanette could understand why her mother had gone on such a bender.

“But surely it can’t be what they say…”

Jeanette’s voice in the empty room seemed strange to her ears. It was as if someone else were speaking. She shivered. She looked again at the family tree, all those deaths in ten-year intervals. Then, taking a deep breath, she opened the door and called the family back into the room.

Uncle Howard came first, his face a mask of pain under his shock of white hair. Then her brothers, who’d been through all this before, guilt stricken that their names hadn’t been drawn. Then her cousin Douglas and his children, who kept their eyes away from hers. Finally there was Aunt Margaret, the bitterest of them all.

“I’ll spend the night in the room,” Jeanette announced. “And in the morning you’ll see all of this was unnecessary worry.”

“But, my dear,” Uncle Howard said, “it is important that you go in understanding what you face-”

“If what you say has any merit,” she said efficiently, “then perhaps it might be better if I entered the room with a healthy skepticism. If I remember my history books correctly, Franklin Roosevelt once said the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. Perhaps it has been our own fear that has claimed us in the past.”

Yet even as she said the words, she knew her father had not been a man to give in to fear. She might try to cling to an idea that the deaths had all been hysterical reactions to the outrageous tales her family spun, but her theory collapsed when she applied it to her own father, a well-decorated Navy pilot in World War II who had looked death in the face many times. It hadn’t been hysterical fear that had stopped his heart in that basement room ten years ago. Standing there in front of her family, Jeanette began to accept the terrifying fact that what her uncle had told her must be true-no matter how much she still outwardly denied it.