The answer, in pencil - including what looked like a false start - had been drawn beneath the question and was signed Harry Keogh :

Jamieson stared at it, stared harder, opened his mouth to speak but said nothing. Hannant could see him rapidly adding up the columns, lines, diagonals - could almost hear his brain ticking over. 'This is ... very good,' Jamieson finally said.

'It's better than that,' Hannant told him. 'It's perfect!'

The head blinked at him. 'Perfect, George? But all magic squares are perfect. That's the lure of them. That's their magic!'

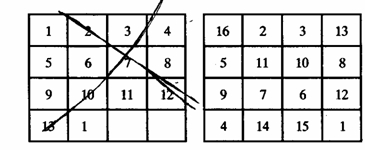

'Yes,' Hannant agreed, 'but there's perfect and there's perfect. You asked for columns, lines, diagonals all total ling the same. He's given you that and far more. The corners total the same. The four squares in the middle total the same. The four blocks of four total the same. Even the opposing middle numbers at the sides come out the same! And if you look closer, that's not the end of it. No, it is perfect.'

Jamieson checked again, frowned for a moment, then smiled delightedly. And finally: 'Where's Keogh now?' 'He's outside. I thought you might like to see him...' Jamieson sighed, sat down at his desk. 'All right, George, let's have your prodigy in, shall we?' Hannant opened the door, called Keogh in. Harry entered nervously, fidgeted where he stood before the head's desk.

'Young Keogh,' said the head, 'Mr. Hannant tells me you've a thing for numbers.' Harry said nothing.

'This magic square, for instance. Now, I've fiddled about with such things - purely for my own amusement, you understand - ever since, oh, since I was about your age. But I don't think I ever came up with a solution as good as this one. It's quite remarkable. Did anyone help you with it?'

Harry looked up, looked straight into Jamieson's eyes. For a moment he looked - scared? Possibly, but in the next moment he went on the defensive. 'No, sir. No one helped me.'

Jamieson nodded. 'I see. So where's your rough work? I mean, one doesn't just guess something as clever as this, does one?'

'No, sir,' said Harry. 'My rough work is there, crossed out.'

Jamieson looked at the paper, scratched his very nearly bald head, glanced at Hannant. Then he stared at Keogh. 'But this is simply a box with the numbers laid in their numerical sequence. I can't see how - '

'Sir,' Harry stopped him, 'it seemed to me that was the logical way to start. When I got that far I could see what needed doing.'

Again the head and the maths teacher exchanged glances.

'Go on, Harry,' said the head, nodding.

'See, sir, if you just write the numbers in, like I did, all the big numbers go to the right and to the bottom. So I asked myself: how can I get half of them over from right to left and half of them from the bottom to the top? And: how can I do both at the same time?'

'That seems... logical' Jamieson scratched his head again. 'So what did you do?'

'Pardon?'

'I said, what - did - you - do, boy!' Jamieson hated having to repeat himself to pupils. They should hang on his every word.

Harry was suddenly pale. He said something but it came out a croak. He coughed and his voice dropped an octave or two. When he spoke again he no longer sounded like a small boy at all. 'It's there in front of you,' he said. 'Can't you see it for yourself?'

Jamieson's eyes bugged and his jaw dropped, but before he could explode Harry added: 'I reversed the diagonals, that's all. It was the obvious answer, the only logical answer. Any other way's a game of chance, trial and error. And hit and miss isn't good enough. Not for me...'

Jamieson stood up, flopped down again, pointed an enraged finger at the door. 'Hannant, get - that - boy -out - of - here! Then come back in and speak to me.'

Hannant grabbed Keogh's arm, dragged him out into the corridor. He had the feeling that if he hadn't physically taken hold of the boy, then Keogh might well have fainted. As it was he propped him up against the wall, hissed 'Wait here!' and left him there looking slightly dazed and sick.

Back inside Jamieson's study, Hannant found the head master soaking sweat from his brow with a large sheet of school blotting paper. He was staring fixedly at Harry's solution and muttering to himself. 'Reversed the diag onals! Hmm! And so he has!' But as Hannant closed the door behind him Jamieson looked up and grinned somewhat feebly. He had obviously regained his self control and continued to dab away at the sweat on his forehead and neck. 'This bloody heat!' he said, waving a limp hand and indicating that Hannant should take a seat.

Hannant, whose shirt was sticking to his back beneath his jacket, said, 'I know. It's murder, isn't it? The school's like a furnace - and it's just as bad for the kids.' He remained standing.

Jamieson saw his meaning and nodded. 'Yes, well that's no excuse for insolence - or arrogance.'

Hannant knew he should keep quiet but couldn't. ' he was being insolent,' he said. 'Thing is, I believe he was simply stating a fact. It was the same when I crossed him yesterday. It seems that as soon as you crowd him he gets his back up. The lad's brilliant - but he'd like to pretend not to be! He does his damnedest to keep it hidden.'

'But why? Surely that's not normal. Most boys of his age like the chance to show off. Is it simply that he's shy - or does it go deeper than that?'

Hannant shook his head. 'I don't know. Let me tell you about yesterday.'

When he was through, the head said: 'Almost exactly parallel to what we've just seen.'

'That's right.'

Jamieson grew thoughtful. 'If he really is as clever as you seem to think he is - and certainly he seems to have an intuitive knack in some directions - then I'd hate to be the one to deprive him of a chance to get somewhere in life.' He sat back. 'Very well, it's decided. Keogh missed the exams through no fault of his own, so ... I'll speak to Jack Harmon at the Tech., see if we can fix up some

sort of private examination for him. Of course I can't promise anything, but - ' 'It's better than nothing,' Hannant finished it for him.

'Thanks, Howard.'

Tine, fine. I'll let you know how I get on.' Nodding, Hannant went out into the corridor where

Keogh was waiting.

Over the next two days Hannant tried to put Keogh to the back of his mind but it didn't work. In the middle of lessons, or at home during the long autumn evenings, even occasionally in the dead of night, the boy's young-old face would be there, hovering on the periphery of Hannant's awareness. Friday night saw the teacher awake at 3:00 a.m., all his windows open to let in what little breeze there was, prowling the house in his pyjamas. He had come awake with that picture in his mind of Harry Keogh, clutching Jamieson's folded sheet of A4, heading off across the schoolyard of milling boys in the direction of the back gate under the stone archway; then of the boy crossing the dusty summer lane and passing in through the iron gates of the cemetery. And Hannant had believed that he knew where Harry was going. And suddenly, though the night had not grown noticeably cooler, Hannant had felt chilly in a way he was now becoming used to. It could only be a psychic chill, he suspected, warning him that something was dreadfully wrong. There was something uncanny about Keogh, certainly, but what it was defied conjecture - or rather, challenged it. One thing was certain: George Hannant hoped to God the kid could pass whatever exams Howard Jamieson and Jack Harmon of Hartlepool Tech. cooked up for him. And it was no longer simply that he wanted the boy to realise his full potential. No, it was more basic than that. Frankly, he wanted Keogh out of here, out of the school, away from the other kids. Those perfectly ordinary, normal boys at Harden Secondary Modern.