He gave way to the fear that had come with her, the sense of the breaking of promises, the incoherence of time. He broke. He began to cry, trying to hide his face in the shelter of his arms, for he could not find the strength to turn over. One of the old men, the sick old men, came and sat on the side of the cot and patted his shoulder. “It’s all right, brother. It’ll be all right, little brother,” he muttered. Shevek heard him and felt his touch, but took no comfort in it. Even from the brother there is no comfort in the bad hour, in the dark at the foot of the wall.

Chapter 5

Shevek ended his career as a tourist with relief. The new term was opening at Ieu Eun; now he could settle down to live, and work, in Paradise, instead of merely looking at it from outside.

He took on two seminars and an open lecture course. No teaching was requested of him, but he had asked if he could teach, and the administrators had arranged the seminars. The open class was neither his idea nor theirs. A delegation of students came and asked him to give it. He consented at once. This was how courses were organized in Anarresti learning centers: by student demand, or on the teacher’s initiative, or by students and teachers together. When he found that the administrators were upset, he laughed. “Do they expect students not to be anarchists?” he said, “What else can the young be? When you are on the bottom, you must organize from the bottom up!” He had no intention of being administered out of the course — he had fought this kind of battle before — and because he communicated his firmness to the students, they held firm. To avoid unpleasant publicity the Rectors of the University gave in, and Shevek began his course to a first-day audience of two thousand. Attendance soon dropped. He stuck to physics, never going off into the personal or the political, and it was physics on a pretty advanced level. But several hundred students continued to come. Some came out of mere curiosity, to see the man from the Moon; others were drawn by Shevek’s personality, by the glimpses of the man and the libertarian which they could catch from his words even when they could not follow his mathematics. And a surprising number of them were capable of following both the philosophy and the mathematics.

They were superbly trained, these students. Their minds were fine, keen, ready. When they weren’t working, they rested. They were not blunted and distracted by a dozen other obligations. They never fell asleep in class because they were tired from having worked on rotational duty the day before. Their society maintained them in complete freedom from want, distraction, and cares.

What they were free to do, however, was another question. It appeared to Shevek that their freedom from obligation was in exact proportion to their lack of freedom of initiative.

He was appalled by the examination system, when it was explained to him; he could not imagine a greater deterrent to the natural wish to learn than this pattern of cramming in information and disgorging it at demand. At first he refused to give any tests or grades, but this upset the University administrators so badly that, not wishing to be discourteous to his hosts, he gave in. He asked his students to write a paper on any problem in physics that interested them, and told them that he would give them all the highest mark, so that the bureaucrats would have something to write on their forms and lists. To his surprise a good many students came to him to complain. They wanted him to set the problems, to ask the right questions; they did not want to think about questions, but to write down the answers they had learned. And some of them objected strongly to his giving everyone the same mark. How could the diligent students be distinguished from the dull ones? What was the good in working hard? If no competitive distinctions were to be made, one might as well do nothing.

“Well, of course,” Shevek said, troubled. “If you do not want to do the work, you should not do it.”

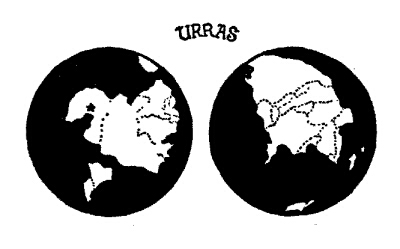

They went away unappeased, but polite. They were pleasant boys, with frank and civil manners. Shevek’s readings in Urrasti history led him to decide that they were, in fact, though the word was seldom used these days, aristocrats. In feudal times the aristocracy had sent their sons to university, conferring superiority on the institution. Nowadays it was the other way round: the university conferred superiority on the man. They told Shevek with pride that the competition for scholarships to Ieu Eun was stiffer every year, proving the essential democracy of the institution. He said, “You put another lock on the door and call it democracy.” He liked his polite, intelligent students, but he felt no great warmth towards any of them. They were planning careers as academic or industrial scientists, and what they learned from him was to them a means to that end, success in their careers. They either had, or denied the importance of, anything else he might have offered them.

He found himself, therefore, with no duties at all beyond the preparation of his three classes; the rest of his time was all his own. He had not been in a situation like this since his early twenties, his first years at tbe Institute in Abbenay, Since those years his social and personal life had got more and more complicated and demanding. He had been not only a physicist but also a partner, a father, an Odonian, and finally a social reformer. As such, he had not been sheltered, and had expected no shelter, from whatever cares and responsibilities came to him. He had not been free from anything: only free to do anything. Here, it was the other way around. Like all the students and professors, he had nothing to do but his intellectual work, literally nothing. The beds were made for them, the rooms were swept for them, the routine of the college was managed for them, the way was made plain for them. And no wives, no families. No women at all. Students at the University were not permitted to marry. Married professors usually lived during the five class days of the seven-day week in bachelor quarters on campus, going home only on weekends. Nothing distracted. Complete leisure to work; all materials at hand; intellectual stimulation, argument, conversation whenever wanted; no pressures. Paradise indeed! But he seemed unable to get to work.

There was something lacking — in him, he thought, not in the place. He was not up to it. He was not strong enough to take what was so generously offered. He felt himself dry and arid, like a desert plant, in this beautiful oasis. Life on Anarres had sealed him, closed off his soul; the waters of life welled all around him, and yet he could not drink.

He forced himself to work, but even there he found no certainty. He seemed to have lost the flair which, in his own estimation of himself, he counted as his main advantage over most other physicists, the sense for where the really important problem lay, the clue that led inward to the center. Here, he seemed to have no sense of direction. He worked at the Light Research Laboratories, read a great deal, and wrote three papers that summer and autumn: a productive half year, by normal standards. But he knew that in fact he had done nothing real.

Indeed the longer he lived on Urras, the less real it became to him. It seemed to be slipping out of his grasp — all that vital, magnificent, inexhaustible world which he had seen from the windows of his room, his first day on the world. It slipped out of his awkward, foreign hands, eluded him, and when he looked again he was holding something quite different, something be had not wanted at all, a kind of waste paper, wrappings, rubbish.

He got money for the papers he wrote. He already had in an account in the National Bank the 10,000 International Monetary Units of the Seo Oen award, and a grant of 5,000 from the Ioti Government. That sum was now augmented by his salary as a professor and the money paid him by the University Press for the three monographs. At first all this seemed funny to him; then it made him uneasy. He must not dismiss as ridiculous what was, after all, of tremendous importance here. He tried to read an elementary economics text; it bored him past endurance, it was like listening to somebody interminably recounting a long and stupid dream. He could not force himself to understand how banks functioned and so forth, because all the operations of capitalism were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion, as barbaric, as elaborate, and as unnecessary. In a human sacrifice to deity there might be at least a mistaken and terrible beauty; in the rites of the moneychangers, where greed, laziness, and envy were assumed to move all men’s acts, even the terrible became banal. Shevek looked at this monstrous pettiness with contempt, and without interest. He did not admit, he could not admit, that in fact it frightened him.