“You know, I don’t agree,” he said to long-faced Vokep, an agricultural chemist traveling to Abbenay. “I think men mostly have to learn to be anarchists. Women don’t have to learn.”

Vokep shook his head grimly. “It’s the kids,” he said. “Having babies. Makes ’em propertarians. They won’t let go.” He sighed. “Touch and go, brother, that’s the rule. Don’t ever let yourself be owned.”

Shevek smiled and drank his fruit juice. “I won’t,” he said.

It was a joy to him to come back to the Regional Institute, to see the low hills patchy with bronze-leaved scrub holum, the kitchen gardens, domiciles, dormitories, workshops, classrooms, laboratories, where he had lived since he was thirteen. He would always be one for whom the return was as important as the voyage out. To go was not enough for him, only half enough; he must come back. In such a tendency was already foreshadowed, perhaps, the nature of the immense exploration he was to undertake into the extremes of the comprehensible. He would most likely not have embarked on that years-long enterprise had he not had profound assurance that return was possible, even though he himself might not return; that indeed the very nature of the voyage, like a circumnavigation of the globe, implied return. You shall not go down twice to the same river, nor can you go home again. That he knew; indeed it was the basis of his view of the world. Yet from that acceptance of transience he evolved his vast theory, wherein what is most changeable is shown to be fullest of eternity, and your relationship to the river, and the river’s relationship to you and to itself, turns out to be at once more complex and more reassuring than a mere lack of identity. You can go home again, the General Temporal Theory asserts, so long as you understand that home is a place where you have never been.

He was glad, then, to get back to what was as close to a home as he had or wanted. But he found his friends there rather callow. He had grown up a good deal, this past year. Some of the girls had kept up with him, or passed him; they had become women. He kept clear, however, of anything but casual contact with the girls, because he really didn’t want another big binge of sex just yet; he had some other things to do. He saw that the brightest of the girls, like Rovab, were equally casual and wary; in the labs and work crews or in the dormitory common rooms, they behaved as good comrades and nothing else. The girls wanted to complete their training and start their research or find a post they liked, before they bore a child; but they were no longer satisfied with adolescent sexual experimentation. They wanted a mature relationship, not a sterile one; but not yet, not quite yet.

These girls were good companions, friendly and independent. The boys Shevek’s age seemed stuck in the end of a childishness that was running a bit thin and dry. They were overintellectual. They didn’t seem to want to commit themselves either to work or to sex. To hear Tirin talk he was the man who invented copulation, but all his affairs were with girls of fifteen or sixteen; he shied away from the ones his own age. Bedap, never very energetic sexually, accepted the homage of a younger boy who had a homosexual-idealistic crush on him, and let that suffice him. He seemed to take nothing seriously; he had become ironical and secretive. Shevek felt cut out from his friendship. No friendship held; even Tirin was too self-centered, and lately too moody, to reassert the old bond — if Shevek had wanted it. In fact, he did not. He welcomed isolation with all his heart. It never occurred to him that the reserve he met in Bedap and Tirin might be a response; that his gentle but already formidably hermetic character might form its own ambience, which only great strength, or great devotion, could withstand. All he noticed, really, was that he had plenty of time to work at last.

Down in Southeast, after he had got used to the steady physical labor, and had stopped wasting his brain on code messages and his semen on wet dreams, he had begun to have some ideas. Now he was free to work these ideas out, to see if there was anything in them.

The senior physicist at the Institute was named Mitis. She was not at present directing the physics curriculum, as all administrative jobs rotated annually among the twenty permanent postings, but she had been at the place thirty years, and had the best mind among them. There was always a kind of psychological clear space around Mitis, like the lack of crowds around the peak of a mountain. The absence of all enhancements and enforcements of authority left the real thing plain. There are people of inherent authority; some emperors actually have new clothes.

“I sent that paper you did on Relative Frequency to Sabul, in Abbenay,” she said to Shevek, in her abrupt, companionable way. “Want to see the answer?”

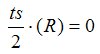

She pushed across the table a ragged bit of paper, evidently a corner torn off a larger piece. On it in tiny scribbled characters was one equation:

Shevek put his weight on his hands on the table and looked down at the bit of paper with a steady gaze. His eyes were light, and the light from the window filled them so they seemed clear as water. He was nineteen, Mitis fifty-five. She watched him with compassion and admiration.

“That’s what’s missing,” he said. His hand had found a pencil on the table. He began scribbling on the fragment of paper. As he wrote, his colorless face, silvered with fine short hair, became flushed, and his ears turned red.

Mitis moved surreptitiously around behind the table to sit down. She had circulatory trouble in her legs, and needed to sit down. Her movement, however, disturbed Shevek. He looked up with a cold annoyed stare.

“I can finish this in a day or two,” he said.

“Sabul wants to see the results when you’ve worked it out.”

There was a pause. Shevek’s color returned to normal, and he became aware again of the presence of Mitis, whom he loved. “Why did you send the paper to Sabul?” he asked. “With that big hole in it!” He smiled; the pleasure of patching the hole in his thinking made him radiant.

“I thought he might see where you went wrong. I couldn’t. Also I wanted him to see what you were after… He’ll want you to come there, to Abbenay, you know.”

The young man did not answer.

“Do you want to go?”

“Not yet.”

“So I judged. But you must go. For the books, and for the minds you’ll meet there. You will not waste that mind in a desert!” Mitis spoke with sudden passion. “It’s your duty to seek out the best, Shevek. Don’t let false egalitarianism ever trick you. You’ll work with Sabul, he’s good, he’ll work you hard. But you should be free to find the line you want to follow. Stay here one more quarter, then go. And take care, in Abbenay. Keep free. Power inheres in a center. You’re going to the center. I don’t know Sabul well; I know nothing against him; but keep this in mind: you will be his man.”

The singular forms of the possessive pronoun in Pravic were used mostly for emphasis; idiom avoided them. Little children might say “my mother,” but very soon they learned to say “the mother.” Instead of “my hand hurts,” it was “the hand hurts me,” and so on; to say “this one is mine and that’s yours” in Pravic, one said. “I use this one and you use that” Mitis’s statement, “You will be his man,” had a strange sound to it. Shevek looked at her blankly.

“There’s work for you to do,” Mitis said. She had black eyes, they flashed as if with anger. “Do it!” Then she went out, for a group was waiting for her in the lab. Confused, Shevek looked down at the bit of scribbled paper. He thought Mitis had been telling him to hurry up and correct his equations. It was not till much later that he understood what she had been telling him.