'Yeah?' Bill asked, interested. 'Did he d-d-die?'

'No, but he was out of school a week.'

'It doesn't matter if it stopped or not,' Eddie said gloomily. 'She'll take me anyway. She'll think it's broken and I go t pieces of bone sticking in my brain, or something.'

'C-C-Can you get bones in your buh-buh-brain ?' Bill asked. This was turning into the most interesting conversation he'd had in weeks.

'I don't know. If you listen to my mother, you can get anything.' Eddie turned to Ben again. 'She takes me down to the Mergency Room about once or twice a month. I hate that place. There was this orderly once? He told her they oughtta make her pay rent. She was really PO'd.'

'Wow,' Ben said. He thought Eddie's mother must be really weird. He was unconscious of the fact that now both of his hands were fiddling in the remains of his sweatshirt. 'Why don't you just say no? Say something like "Hey Ma, I feel all right, I just want to stay home and watch Sea Hunt." Like that.'

'Awww,' Eddie said uncomfortably, and said no more.

'You're Ben H-H-H-Hanscom, r-right?' Bill asked.

'Yeah. You're Bill Denbrough.'

'Yuh-Yes. And this is Eh-Eh –Eh –heh-Eh –Eh — '

'Eddie Kaspbrak,' Eddie said. 'I hate it when yo u stutter my name, Bill. You sound like Elmer Fudd.'

'Suh-horry.'

'Well, I'm pleased to meet you both,' Ben said. It came out sounding prissy and a little lame. A silence fell amid the three of them. It was not an entirely uncomfortable silence. In it they became friends.

'Why were those guys chasing you?' Eddie asked at last.

'They're a-a-always chuh-hasing s –someone,' Bill said. 'I h-hate those fuckers.'

Ben was silent a moment — mostly in admiration — before Bill's use of what Ben's mother sometimes called The Really Bad Word. Ben had never said The Really Bad Word out loud in his whole life, although he had written it (in extremely small letters) on a telephone pole the Halloween before last.

'Bowers ended up sitting next to me during the exams,' Ben said at last. 'He wanted to copy off my paper. I wouldn't let him.'

'You must want to die young, kid,' Eddie said admiringly.

Stuttering Bill burst out laughing. Ben looked at him sharply, decided he wasn't being laughed at, exactly (it was hard to say how he knew it, but he did), and grinned.

'I guess I must,' he said. 'Anyway, he's got to take summer-school, and he and those other two guys were laying for me, and that's what happened.'

'Y-You look like t-t-they kuh-hilled you,' Bill said.

'I fell down here from Kansas Street. Down the side of the hill.' He looked at Eddie. 'I'll probably see you in the Mergency Room, now that I think about it. When my mom gets a look at my clothes, she'll put me there.'

Both Bill and Eddie burst out laughing this time, and Ben joined them. It hurt his stomach to laugh but he laughed anyway, shrilly and a little hysterically. Finally he had to sit down on the bank, and the plopping sound his butt made when it hit the dirt got him going all over again. He liked the way his laughter sounded with theirs. It was a sound he had never heard before: not mingled laughter — he had heard that lots of times — b u t m i n g l e d l a u g h t e r o f which his own was a part.

He looked up at Bill Denbrough, their eyes met, and that was all it took to get both of them laughing again.

Bill hitched up his pants, flipped up the collar of his shirt, and began to slouch around in a kind of moody, hoody strut. His voice dropped down low and he said, 'I'm gonna killya, kid. Don't gimme no crap. I'm dumb but I'm big. I can crack walnuts with my forehead. I can piss vinegar and shit cement. My name's Honeybunch Bowers and I'm the boss prick round dese-yere Derry parts.'

Eddie had collapsed to the stream-bank now and was rolling around, clutching his stomach and howling. Ben was doubled up, head between his knees, tears spouting from his eyes, snot hanging from his nose in long white runners, laughing like a hyena.

Bill sat down with them, and little by little the three of them quieted.

'There's one really good thing about it,' Eddie said presently. 'If Bowers is in summer school, we won't see him much down here.'

'You play in the Barrens a lot?' Ben asked. It was an idea that never would have crossed his own mind in a thousand years — not with the reputation the Barrens had — but now that he was down here, it didn't seem bad at all. In fact, this stretch of the low bank was very pleasant as the afternoon made its slow way toward dusk.

'S-S-Sure. It's n-neat. M-Mostly n-nobody b-buh-bothers u-us down h-here. We guh-guh-hoof off a lot. B-B-Bowers and those uh-other g-guys don't come d-down here eh-eh-anyway.'

'You and Eddie?'

'Ruh-Ruh-Ruh — ' Bill shook his head. His face knotted up like a wet dishrag when he stuttered, Ben noticed, and suddenly an odd thought occurred to him: Bill hadn't stuttered at all when he was mocking the way Henry Bowers talked. 'Richie!' Bill exclaimed now, paused a moment, and then went on. 'Richie T-Tozier usually c-comes down, too. But h-him and his d– dad were going to clean out their ah– ah– ah — '

'Attic,' Eddie translated, and tossed a stone into the water. Plonk.

'Yeah, I know him,' Ben said. 'You guys come down here a lot, huh?' The idea fascinated him — and made him feel a stupid sort of longing as well.

'Puh-Puh-Pretty much,' Bill said. 'Wuh-Why d-don't you c-c-come back down tuh-huh-morrow? M-Me and E-E-Eddie were tub-trying to make a duh-duh-ham.'

Ben could say nothing. He was astounded not only by the offer but by the simple and unstudied casualness with which it had come.

'Maybe we ought to do something else,' Eddie said. 'The dam wasn't working so hot anyway.'

Ben got up and walked down to the stream, brushing the dirt from his huge hams. There were still matted piles of small branches at either side of the stream, but anything else they'd put together had washed away.

'You ought to have some boards,' Ben said. 'Get boards and put em in a row . . . facing each other . . . like the bread of a sandwich.'

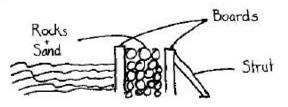

Bill and Eddie were looking at him, puzzled. Ben dropped to one knee. 'Look,' he said. 'Boards here and here. You stick em in the streambed facing each other. Okay? Then, before the water can wash them away, you fill up the space between them with rocks and sand — '

'Wuh-Wuh-We,' Bill said.

'Huh?'

'Wuh-We do it.'

'Oh,' Ben said, feeling (and looking, he was sure) extremely stupid. But he didn't care if he looked stupid, because he suddenly felt very happy. He couldn't even remember the last time he felt this happy. 'Yeah. We. Anyway, if you — we — fill up the space in between with rocks and stuff, it'll stay. The upstream board will lean back against the rocks and dirt as the

water piles up. The second board would tilt back and wash away after awhile, I guess, but if we had a third board . . . well, look.'

He drew in the dirt with a stick. Bill and Eddie Kaspbrak leaned over and studied this little drawing with sober interest:

'You ever built a dam before?' Eddie asked. His tone was respectful, almost awed.

'Nope.'

'Then h-h-how do you know this'll w-w-work?'

Ben looked at Bill, puzzled. 'Sure it will,' he said. 'Why wouldn't it?'

'But h-how do you nuh-nuh-know ?' Bill asked. Ben recognize d the tone of the question as one not of sarcastic disbelief but honest interest. 'H-How can y-you tell?'

'I just know,' Ben said. He looked down at his drawing in the dirt again as if to confirm it to himself. He had never seen a cofferdam in his life , either in diagram or in fact, and had no idea that he had just drawn a pretty fair representation of one.