Aharon went past the Dung Gate, down a set of stairs, and through a security checkpoint. The soldiers knew him but insisted on patting him down. Orthodox rabbis drew as much suspicion as Palestinians these days, but with the crazy state of the world, who could blame them? Then he was through and in front of HaKotel, the Western Wall, the only remnant of the Second Temple.

The light was rosy, pinkening the cream-colored edifice. As always, he approached with a sense of privilege, of excitement, like a bridegroom. He crossed to the wall, lowering his hands gently to the cold stone, then his forehead, with the tender sigh of a lover.

Around him were several dozen others saying their morning prayers at this sacred spot. Some were haredim with beards, side-locks, and fur hats. Aharon, who was Orthodox but not haredim, had a beard but no side-locks, and his hat was a simple black wool fedora with a kippa, a skullcap, underneath.

He joined a minyan of early risers from his synagogue and opened his briefcase. He took out his tallith and tefillin, kissing them. He wrapped himself in the prayer shawl and put on the ancient leather straps with their boxes of Scripture on first his left arm, then his forehead. And he began to pray, rocking in front of the wall.

Even though there was no pretense in it, he was not unaware of the picture he made: stately, paternal, rabbinical. He was proud to be making it. Someone had to show the world what being a Jew was all about.

An hour later, Aharon was in his office at Aish HaTorah. Aish HaTorah was a “master of the return” school, designed to teach Unorthodox Jews the ways of Orthodoxy. The Jews in question were usually young Americans whose parents were nonpracticing or (which was maybe worse) Conservative or Reformed. Aharon taught Talmud and Midrash. It wasn’t much money, but it placed him across from the wall all day, and his class schedule left him plenty of time to pursue his real passion—Torah code.

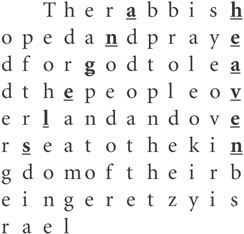

The code was the flame in Aharon’s heart. The greatest rabbis had always known there were messages hidden in the Torah, but the sages, may they rest in peace, didn’t have microchips. Now you could run a program, give it a keyword like heaven, and the search routine would scan the Hebrew letters of the Torah looking for the keyword hidden in the text. A “hidden” word appeared via Equidistant Letter Spacing—the ELS or skip. For example, the plaintext phrase “The Rabbis hoped and prayed for God to lead the people over land and over sea to the kingdom of their being, Eretz Yisrael” contained the hidden word heaven at a skip of eleven: “The Rabbis hoped and prayed for God to lead the people over land and over sea to the kingdom of their being, Eretz Yisrael.”

What had really stunned the world was the presence of arrays of related words and phrases in the Hebrew Bible. Arrays were arrangements of the plaintext letters into columns the width of the skip. These arrays made it easier to find related words or phrases near the original keyword.

The fact that such arrays were sought in the Hebrew version of the text made the task both easier and harder.

But… the scientific community was outraged, naturally. What good could atheists have to say about divinely implanted messages? Their most damning rebuttal showed that similar “themed word arrays” could be found in any text—War and Peace, for example. Hence Aharon’s current line of research.

He was still puzzling over the latest stack of printouts when Binyamin Yoriv came in.

“Good!” Aharon grunted. “I have a riddle for you.”

“Is that from last night’s test?” Binyamin crossed to the desk.

Aharon shrank back. The boy had halitosis and a skin problem that left scales in his wake. It was written that God gave everyone a mix of assets and flaws, but Binyamin’s assets, like the Torah code itself, were extremely well hidden.

“What happened?” Binyamin asked. “Was there a bug in the program?”

“No.”

“But there are too many pages.”

“Nothing is lost on you, Binyamin.”

Aharon waited for the boy to catch on as he scanned the three-inch stack. His scaly eyebrows went up. “Hey, one of our search phrases, ‘Yosef Kobinski,’ is really in all these arrays. That’s strange.”

“Strange? Three hundred arrays for one little rabbi. As usual, you understate the case.”

Aharon wheeled his chair to the left, not only to get away from Binyamin’s exhalation zone but also to pick up Chachik’s Encyclopedia—a Who’s Who of Jewish scholars. “I would say my theory has been disproven, wouldn’t you?”

“What was your theory?”

Aharon felt a spark of aggravation. He had explained this three or four times already. “Witzum, Rips, and Rosenberg, in their Statistical Science article, took the names of the thirty greatest rabbis from this very encyclopedia. They found code arrays for each rabbi where his name appeared close to his birth and death dates, nu?”

“I know.”

“That’s good that you know. I know, too.”

“So—”

“So they took the rabbis with the longest entries in this encyclopedia. I took the shortest.”

“What for?”

“Think!”

Binyamin appeared to give it a legitimate effort. He shrugged.

“Someday you’re going to learn how to use that brain of yours. Then again, someday the dead will rise, so it is written.”

“Rabbi—”

“So we run the same test they did with a new set of data; that is point one. If we find arrays for all these rabbis also, it is further proof of the code. As for my own theory, I had a little idea that the ‘lesser’ rabbis would appear in the code less often than the ‘greater’ rabbis. If we could show that it would be very difficult to explain with War and Peace!”

Binyamin pointed to the open encyclopedia. “But Rabbi Kobinski has only one paragraph, yet he appears in three hundred arrays. That’s even more than the Ba’al Shem Tov, the most famous rabbi ever.”

Aharon tapped his temple, looking pained. “Didn’t I say it disproved my theory?”

“So how come—”

“That’s the question, Binyamin, how come, as you so eloquently put it.”

“Must be a characteristic of the name—common letters or something.”

Aharon stroked his beard. “Yosef—perhaps. But the phrase we searched for was ‘Yosef Kobinski.’ How common could it be?” Aharon picked up Chachik’s and began reading the Kobinski entry out loud: “ ‘Yosef Kobinski, Brezeziny, Poland. Born, Tish’ah b’Av 5660.’ ”

“Nineteen hundred,” Binyamin calculated quickly.

“ ‘Died Kislev 5704.’ ”

“November 1943.”

Aharon rolled his eyes. The boy had failed a test on dates last month. As usual, he had learned it only after the rest of the class had moved on.

“ ‘Rabbi Kobinski was a student of Rabbi Eleazar Zaks, the famous kabbalist of Brezeziny. He studied physics at the University of Warsaw and later taught there before leaving to pursue kabbalah. Rabbi Kobinski was considered by many to be a genius of kabbalah. His first and only book, The Book of Mercy, was a prelude to great things. Unfortunately, he was lost in the Holocaust when he died at Auschwitz.’ ”

Aharon leaned back, the chair groaning with his weight. Yes, this certainly killed his theory. Who had even heard of Kobinski-of-the-300-arrays? Nobody. A burning in his chest bothered him enough that he popped antacids from his linty pocket. He noticed that his fingers were puffy. (Salt, Hannah would say, heart, she’d remind him, and he’d ignore her.)