Finally, the transformation of Europe has also been differentiated by individualism. The historian and anthropologist Alan Macfarlane has described individualism as ‘the view that society is constituted of autonomous, equal units, namely separate individuals, and that such individuals are more important, ultimately, than any larger constituent group.’ [97] This is very different from East and South Asian cultures, where group rather than individual identity is central. Take the family, for example. The English family system had its origins in the thirteenth century and, courtesy of the Pilgrims, it also became the basis of the family system in North America. This individualistic system, with its emphasis on the nuclear family, stands in stark contrast to the traditional extended-household, arranged-marriage, kinship-based systems to be found in societies like China and India, whose values and distinctive characteristics persist to this day, notwithstanding urbanization and a dramatic fall in the size of the nuclear family. [98] Thus, while marriage in the West is essentially a union of two individuals, in Chinese and Indian culture it involves the conjoining of two families.

Europe’s journey to and through modernity took highly specific and unique forms — the relative absence of an external threat, colonialism, the preponderance of industry, relatively slow growth, a pattern of intra-European conflict (or what I have termed ‘internal wars’), and individualism. We should not therefore be surprised that the characteristics of its modernity are also more distinctive than is often admitted. Since Europe has enjoyed such a huge influence on the rest of the world, however, distinguishing between the specific and the universal is often difficult and elusive. Europeans, unsurprisingly, have long believed that what they have achieved must be of universal application, by force if necessary. It is only with the rise of a range of new modernities that it is becoming possible to distinguish between what is universal and what is specific about the European experience.

THE DOMINANCE OF EUROPE

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, GDP per head in Western Europe and on the North American seaboard was perhaps twice that of South Asia and roughly on a par with Japan and the southern and eastern seaboard of China. By 1900, income per head in Western Europe and the North American seaboard dwarfed that of China by a margin of at least ten times. China was to pay dearly for its inability to overcome the economic constraints that began to bear down on it during the late eighteenth century; in contrast, Europe luxuriated in its good fortune. The key to Europe ’s transformation was the Industrial Revolution. Britain ’s was well under way before 1800; by the second half of the nineteenth century, it had been joined by much of Western Europe. Previously economic growth was of a glacial speed; now compound rates of growth ensured that Western Europe far outdistanced every other part of the world, the United States being the most important exception. Apart from North America, the old white settler colonies [99] and Japan after 1868, Europe enjoyed a more or less total monopoly of industrialization during the nineteenth century, a scenario with profound consequences for everyone else.

The economic chasm that opened up between Europe and nearly everywhere else greatly enhanced its ability to dominate the world. [100] The colonial era had started in the seventeenth century, but from the middle of the eighteenth century onwards, with the progressive acquisition of India, it rapidly expanded. In the name of Christianity, civilization and racial superiority, and possessed of armies and navies without peer, the European nations, led by Britain and France, subjugated large swathes of the world, culminating in the scramble for Africa in the decades immediately prior to 1914. [101] Savage wars took place between whites and non-whites as Chinese, Indians and native peoples in North America, Australasia and southern Africa made their last stand against European assaults on their religions, rulers, land and resources. [102] Niall Ferguson writes:

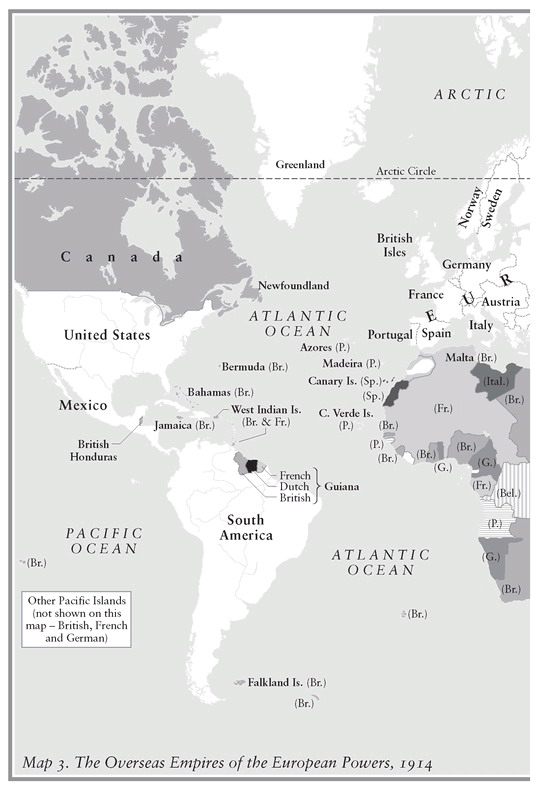

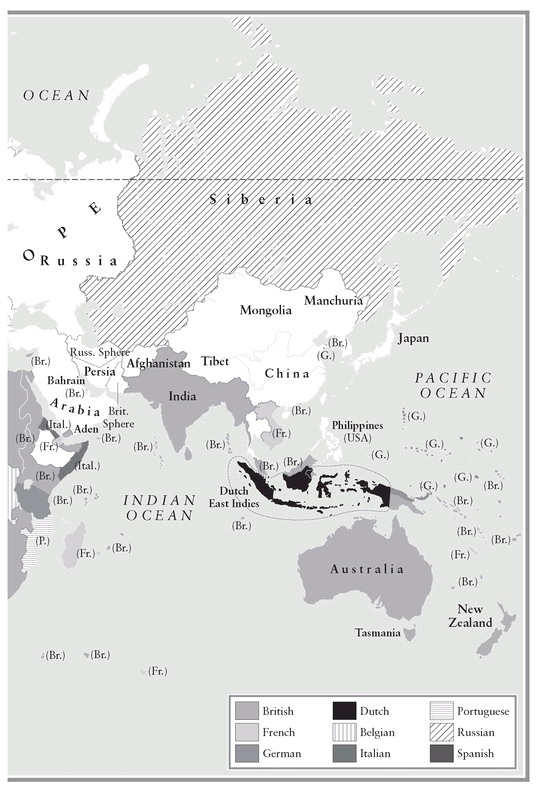

Western hegemony was one of the great asymmetries of world history. Taken together, the metropoles of all the Western empires — the American, Belgian, British, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish — accounted for 7 % of the world’s land surface and just 18 % of its population. Their possessions, however, amounted to 37 % of global territory and 28 % of mankind. And if we regard the Russian empire as effectively another European empire extending into Asia, the total share of these Western empires rises to more than half the world’s area and population. [103]

As the world’s leading power, Britain sought to shape the new global trading system according to its interests. Its national wealth depended on exporting its manufacturing products to as many markets as possible while importing food and raw materials at the lowest possible prices. Laissez-faire was not simply an abstract principle or a disinterested policy. It was the means by which Britain tried to take advantage of its overwhelming advantage in manufacturing and prevent others from seeking to erect tariffs to protect their nascent industries. The international free trade regime championed by Britain had a stifling effect on much of the rest of the world outside north-west Europe and North America. Industrial development in the colonial world was for the most part to prove desperately slow, or non-existent, as the European powers tried to prevent or forestall direct competition for their domestic producers. ‘Whatever the official rhetoric,’ writes Eric Hobsbawm, ‘the function of colonies and informal dependencies was to complement metropolitan economies and not to compete with them.’ [104] The urban population — a key measure of industrialization — in the British and French empires in Asia and North Africa remained stuck at around 10 per cent of the total in 1900, which was barely different from the pre-colonial period, while standards of living may even have fallen over the course of the nineteenth century. [105] India — by far Britain ’s most important colony (it was colonized by the East India Company from the mid eighteenth century, and formally annexed by Britain in 1857) [106] — had a per capita GDP of $550 in 1700, $533 in 1820, and $533 in 1870. In other words, it was lower in 1870 than it had been in 1700, or even 1600. It then rose to $673 in 1914 but fell back to $619 in 1950. Over a period of 250 years, most of it under some form of British rule, India’s per capita GDP increased by a mere 5.5 per cent. Compare that with India ’s fortunes after independence: by 1973 its per capita GDP had risen to $853 and by 2001 to $1,957. [107]

Map 3. The Overseas Empires of the European Powers, 1914

Not only did Europe take off in a manner that eluded Asia after 1800, but it forcibly sought to prevent — by a combination of economic and military means — Asia from taking the same route. China was a classic case in point. The British fought the Chinese in the First Opium War of 1839-42 over the right to sell Indian-grown opium to the Chinese market, which proved a highly profitable trade both for Britain and its Indian colony. The increasingly widespread sale and use of opium following China ’s defeat predict-ably had a debilitating effect on the population, but in the eyes of the British the matter of ‘free trade’ was an altogether higher principle. China ’s ensuing inability to prevent the West from prising open the Chinese market hastened the decline of the Qing dynasty, which by the turn of the century was hopelessly enfeebled. When European and American expeditionary forces invaded China in 1900 to crush the Boxer Uprising, it was evident that little, other than imperial rivalry, stood in the way of China being partitioned in a similar manner to Africa. [108]

[97] Alan Macfarlane, The Origins of English Individualism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1979), p. 196, quoted by Lal, Unintended Consequences, p. 75.

[98] Göran Therborn, Between Sex and Power: Family in the World, 1900-2000 (London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 119-23; also pp. 108-12.

[99] The old white settler colonies enjoyed a very different relationship with Britain to that of the non-white colonies, and this was reflected in their far greater economic prosperity; Angus Maddison, The World Economy: A Millennial Perspective (Paris: OECD, 2006), pp. 184-5.

[100] Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), pp. 48–53; Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), Chapter 3.

[103] Niall Ferguson, ‘ Empire Falls ’, October 2006, posted on www.vanityfair.com, pp. 1–2.