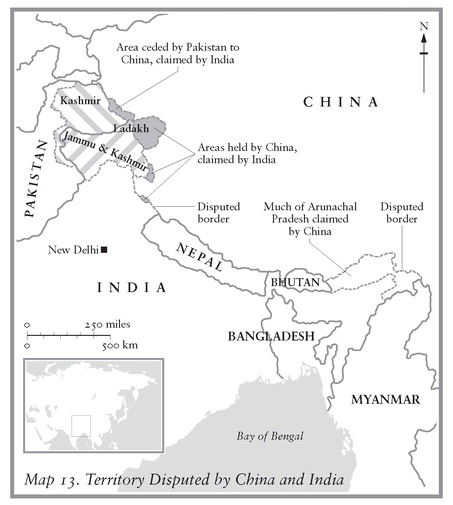

Map 13. Territory Disputed by China and India

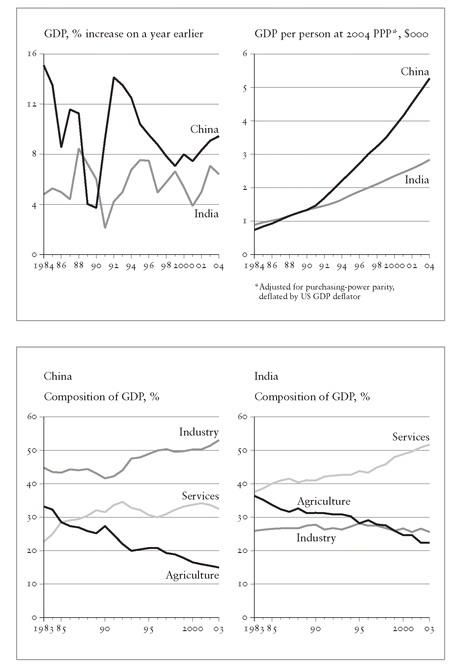

Figure 39. Comparative economic performance of China and India.

EUROPE

China ’s relationship with Europe is significantly different from that with the United States. While the US- China relationship has been a more or less continuous source of domestic debate and controversy, the Europe-China relationship has, until recently, attracted relatively little attention. Relations between Europe and China have hitherto been relatively straightforward and conflict-free. Historically this is a little ironic. After all, it was the European powers, starting with Britain and the Opium Wars, which colonized China, with the United States very much a latecomer to the process. The ‘century of humiliation’ was about Europe, together with Japan, with the United States playing no more than a bit part. The present relationship between Europe and China has been low profile largely because Europe, apart from its economic interests, is no longer a major power in East Asia, a position it relinquished to the United States in the aftermath of the Second World War. That Europe is largely invisible in such an important region of the world bears testimony to its post-1945 global decline and its retreat into an increasingly regional role, a process which continues apace and is likely to accelerate with the rise of China and India. [1134] With the exception of the euro, discussion of Europe ’s wider global role is largely confined to what is known as ‘normative power’, namely the promotion of standards that are negotiated and legitimized within international institutions. [1135] Nonetheless, with an economy rivalling that of the United States in size, together with the fact that it forms the other half of the Western alliance, Europe’s attitude towards China is clearly of some importance.

For the most part, Europe’s response to the rise of China has been low-key, fragmented and incoherent. This is because the European Union lacks the power and authority to act as an overarching centre in Europe’s relations with nations such as China. As a result, Europe generally speaks with a weak voice and more often than not with many voices. The European Union is not a unitary state with the capacity to think and act either strategically or coherently, but an amalgam and representative of different interests. [1136] Europe’s economic relationship with China has grown enormously over the last decade, with a massive increase in imports of cheap Chinese manufactured goods and a very large rise in European exports to China, mainly of relatively high-tech capital goods, especially from Germany. This has resulted in a growing European trade deficit with China as well as a loss of jobs in those industries that compete directly with Chinese imports. Until recently this has aroused very little political debate, certainly nothing like that in the United States. There are several reasons for this. Europe’s trade deficit with China has been much smaller than the US ’s, although this is now changing. Political attention is centred not so much on Europe ’s deficit but on that of individual countries, and even these have so far attracted relatively little concern. In contrast to the United States, there has been little debate about the exchange rate between the renminbi and the euro, though the appreciation of the euro against the renminbi prior to the global recession led to growing European anxiety and representations to Beijing about the need for a revaluation of their currency. Finally, Europe has been overwhelmingly preoccupied with the effects of the recent enormous enlargement of the EU, not least the large-scale migration of workers from Eastern and Central Europe to Western Europe, [1137] which has had a much greater impact, and certainly been more politically sensitive, than China.

As a consequence, the levels of concern in Europe about the economic repercussions of China ’s rise have been relatively muted; but with increased anxiety about the value of the renminbi and the growing trade deficit, there have been signs that this might change. [1138] The predominant view in most countries has been that China ’s rise has on balance been beneficial because of its negative effect on consumer prices, though in the less developed European countries like Portugal and Greece, together with the new entrants — all of which compete in varying degrees with China — the attitude has been more mixed. [1139] However, the credit crunch and the onset of a depression has kindled a mood of anxiety in many European countries, perhaps especially France and Italy, about the effects of globalization and the impact of China’s rise. [1140] The result has been increased economic tension with China, raising the possibility of limited forms of action, such as anti-dumping duties and anti-subsidy tariffs, against Chinese imports. [1141] While previously China ’s economic rise was seen as largely benign, and for the most part beneficial, the mood has become less sanguine amid growing concern about its possible consequences for Europe. A further factor fuelling this anxiety is the fear of investments by Chinese multinationals and by the Chinese Investment Corporation in key European industries.

In the longer run, as Chinese companies progressively move up the technological ladder and develop brands which compete head-on with those from Europe, the number of losers could escalate considerably and fuel a demand for protection against ‘unfair’ competition from China, perhaps culminating in Europe steadily raising protectionist barriers against China, a move which would have profound political repercussions. [1142] At this stage, however, it is premature to predict what the likely political effects of China ’s growing competitive challenge to Europe might be in the future.

The lack of any serious European diplomatic or military presence in East Asia means that, unlike the United States, which remains the key arbiter of security in the region, Europe has no major geopolitical conflicts of interest with China. When it comes to Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula or the US-Japanese alliance, all critical issues of US concern, Europe is no more than a spectator. It has no involvement in the United States ’ bilateral alliance system in the region. As a result, Chinese-European relations are unencumbered by such considerations. The nearest such issue has been the European embargo on the supply of arms to China, which was introduced after Tiananmen Square and which China has lobbied hard to get lifted. Although the European Union eventually obliged in 2005, it rapidly reversed the decision in response to huge pressure from the United States, which turned the issue into something akin to a vote of confidence in the Atlantic Alliance. Only by making it an article of faith in the West did the US manage to hold the line, suggesting that Europe may, up to a point, be prepared to think for itself when it comes to its relations with China. This is not to suggest that in the long run Europe is likely to detach itself from the United States in favour of China — that is virtually inconceivable — but the reaction of key European nations like Germany and France to the American invasion of Iraq showed that much of Europe was no longer prepared slavishly to follow the US. It is reasonable to surmise that relations between the US and Europe are likely to improve significantly during the Obama presidency, though they are unlikely to return to the intimacy of the Cold War period. With the rise of China and the importance of the Middle East, the transatlantic relationship is no longer pivotal for the US in the way that it once was: rather than being a universal relationship in the mould of the Cold War, the nature of cooperation is likely to vary according to the issue involved. As the focus of global affairs shifts towards the relationship between the United States and China, there is a possibility that Europe might become a freer spirit than previously, and not necessarily always prepared to do the US ’s bidding. But it is important not to exaggerate any such scenario. Europe is far more likely to take the side of the United States than China ’s in geopolitical arguments, whether it be Darfur, trade talks or climate change. For a variety of reasons, historical, cultural, ethnic and economic, Europe is likely to remain very closely wedded to the US in the world that is unfolding.

[1134] Dominique Moisi, ‘Europe Must Not Go the Way of Decadent Venice ’, Financial Times, 12 July 2005.

[1135] For example, Zaki Laïdi, ‘How Europe Can Shape the Global System’, Financial Times, 30 April 2008.

[1136] Katinka Barysch with Charles Grant and Mark Leonard, Embracing the Dragon: The EU’s Partnership with China (London: Centre for European Reform, 2005), p. 77.

[1138] Patrick Messerlin and Razeen Sally, ‘Why It is Dangerous for Europe to Bash China ’, Financial Times, 13 December 2007.

[1139] European Commission, ‘The Challenge to theEUof a Rising China’, in European Competitiveness Report (Luxembourg: 2004).

[1140] In the Italian general election in 2008, growing fears about globalization, amongst other things, were reflected in very big increases in the vote for the anti-globalization, anti-immigration Lega Nord in Milan, Turin, Venice, Bo logna and Florence; Erik Jones, ‘Italy’s Bitterness Could Blight Berlusconi’, Financial Times, 16 April 2008.

[1141] Charles Grant with Katinka Barysch, Can Europe and China Shape a New World Order? (London: Centre for European Reform, 2008), especially pp. 10–13; also Chapter 3.