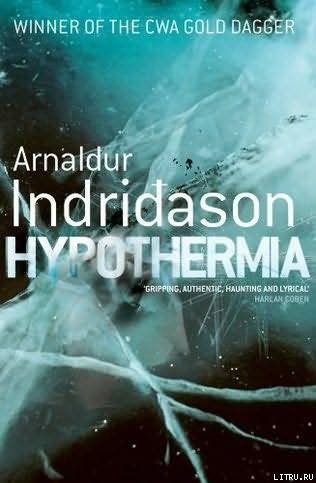

Arnaldur Indriðason

Hypothermia

The sixth book in the Reykjavik Murder Mysteries serie, 2009

Translated by Victoria Cribb

‘The elder brother recovered from his frostbite but

was said to be left gloomy and withdrawn by his ordeal.’

Tragedy on Eskifjördur Moor

María hardly registered what was happening during the funeral. She sat numbly in the front pew, holding Baldvin’s hand, barely conscious of her surroundings or the service. The vicar’s address, the presence of the mourners and the singing of the little church choir all blurred into a single refrain of grief. The vicar had come round to see them beforehand to make notes, so María already knew the contents of her address. It focused for the most part on María’s mother Leonóra’s academic career, the courage she had shown in fighting the dreaded illness, the wide circle of friends she had collected during her life, and María herself, her only daughter, who had to some extent followed in her mother’s footsteps. The vicar touched on Leonóra’s eminence in her field and the care she took to cultivate her friendships, as witnessed by the attendance on that miserable autumn day. Most of the mourners were fellow academics. Leonóra had sometimes mentioned to María how rewarding it was to belong to the intelligentsia. There was an arrogance implicit in her words that María had chosen to ignore.

She remembered the autumn colours in the cemetery and the frozen puddles on the gravel path leading to the grave, the crackling sound as the thin film of ice broke under the feet of the pall-bearers. She remembered the chilly breeze and making the sign of the cross over her mother’s coffin. María had pictured herself in this situation countless times before, ever since it became clear that the disease would kill her mother, and now here she was. She stared at the coffin in the grave and recited a brief mental prayer before making the sign of the cross with her outstretched hand. Then she lingered motionless at the graveside until Baldvin led her away.

She remembered people coming up to her at the reception afterwards to pay their respects. Some offered their assistance, asking if there was anything they could do for her.

María’s mind did not return to the lake until all was quiet again and she was left alone with her thoughts, late that night. It did not occur to her until then, when it was all over and she was thinking back over that gruelling day, that no one from her father’s family had turned up to the funeral.

1

The emergency line received a call from a mobile phone shortly after midnight. An agitated female voice cried:

‘She’s… María’s killed herself… I… it’s horrible… horrible!’

‘What’s your name, please?’

‘Ka – Karen.’

‘Where are you calling from?’ the emergency operator asked.

‘I’m at… it’s… her holiday cottage…’

‘Where? Where is it?’

‘… At Lake Thingvallavatn. At… at her holiday cottage. Please hurry… I… I’ll be here…’

Karen thought she would never find the cottage. It had been a long time, nearly four years, since her last visit. María had given her detailed directions just to be on the safe side, but they had more or less gone in one ear and out the other because Karen had assumed she would remember the way.

It was past eight in the evening and pitch dark by the time she left Reykjavík. She drove over Mosfellsheidi moor where there was little traffic, just the odd pair of headlights passing by on their way to town. Only one other car was travelling east and she hung on its red rear lights, grateful for the company. She didn’t like driving alone in the dark and would have set off earlier if she hadn’t been held up. She worked in the public-relations department of a large bank and it had seemed as if the meetings and phone calls would never let up.

Karen was aware of the mountain Grímannsfell to her right, although she couldn’t see it, and Skálafell to her left. Next she drove past the turning to Vindáshlíd where she had once spent a two-week summer holiday as a child. She followed the red tail lights at a comfortable speed until they drove down through the Kerlingarhraun lava field, and there their ways parted. The red lights accelerated and disappeared into the darkness. She wondered if they were heading for the pass at Uxahryggir and north over the Kaldidalur mountain road. She had often taken that route herself. It was a beautiful drive down the Lundarreykjadalur valley to Borgarfjördur fjord. The memory of a lovely summer’s day once spent at Lake Sandkluftavatn came back to her.

Karen herself turned right and drove on into the blackness of the Thingvellir national park. She had difficulty identifying the landmarks in the gloom. Should she have turned off sooner? Was this the right turning down to the lake? Or was it the next? Had she come too far?

Twice she went wrong and had to turn round. It was a Thursday evening and most of the cottages were empty. She had brought along a supply of food and reading material, and María had told her that they had recently installed a television in the cottage. But Karen’s main intention was to try to sleep, to get some rest. The bank was like a madhouse after the recent abortive takeover. She had reached the point where she could no longer make any sense of the infighting between the different factions among the major shareholders. Press releases were issued at two-hourly intervals and, to make matters worse, it transpired that a severance payment of a hundred million krónur had been promised to one of the bank’s partners, someone whom a particular faction wanted to fire. The board had succeeded in stirring up public outrage, and it was Karen’s job to smooth things over. It had been like this for weeks now and she was at the end of her tether by the time it occurred to her to escape from town. María had often offered to lend her the cottage for a few days, so Karen decided to give her a call. ‘Of course,’ María had said at once.

Karen made her way slowly along a primitive track through low-growing scrub until her headlights lit up the cottage down by the water. María had given her a key and told her where they kept a spare. It was sometimes useful to have an extra key hidden at the cottage.

She was looking forward to waking up tomorrow morning amidst the autumn colours of Thingvellir. For as long as she could remember people had flocked to the national park in the autumn, since few places in the country could boast such a brilliant display of colour as here by the lake where the rust-red and orange shades of the dying leaves extended as far as the eye could see.

She started to ferry her luggage from the car to the sun deck beside the door. Then, putting the key in the lock, she opened the door and groped for the light switch. The light came on in the hallway leading to the kitchen and she took her little suitcase inside and placed it in the master bedroom. To her surprise, the bed was unmade. That was not like María. A towel was lying on the floor of the lavatory. When she turned on the light in the kitchen she became aware of a strange presence. Although she was not afraid of the dark, she felt a sudden sensation of physical unease. The living room was in darkness. By daylight there was a superb view of the lake from its windows.

Karen turned on the living-room light.

Four solid beams extended across the ceiling, and from one of them a body was hanging, its back turned to her.

Shock sent her crashing back against the wall and her head slammed into the wood panelling. Everything went black. The body hung from the beam by a thin blue cord, mirrored in the dark living-room window. She didn’t know how long it was before she dared to inch closer. The tranquil surroundings of the lake had in an instant been converted into the setting for a horror story that she would never forget. Every detail was etched on her memory. The kitchen stool, out of place in the minimalist living room, lying on its side under the body; the blue of the rope; the reflection in the window; the darkness of Thingvellir; the motionless human body suspended from the beam.