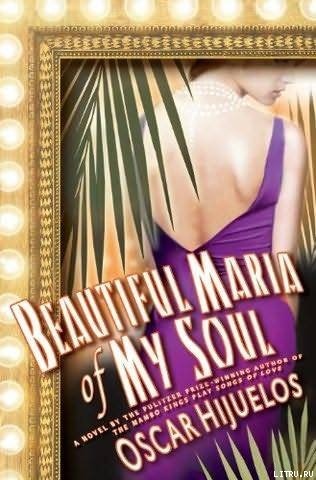

Oscar Hijuelos

Beautiful María of My Soul

© 2010

TO THE MEMORY OF

AUGUST WILSON AND GUILLERMO CABRERA INFANTE

PART I. Cuba, 1947

Chapter ONE

Over forty years before, when Nestor Castillo’s future love, one María García y Cifuentes, left her beloved valle in the far west of Cuba, she could have gone to the provincial capital of Pinar del Río, where her prospects for finding work might be as good-or bad-as in any place; but because the truck driver who’d picked her up one late morning, his gargoyle face hidden under the lowered brim of a lacquered cane hat, wasn’t going that way and because she’d heard so many things-both wonderful and sad-about Havana, María decided to accompany him, that cab stinking to high heaven from the animals in the back and from the thousands of hours he must have driven that truck with its loud diesel engine and manure-stained floor without a proper cleaning. He couldn’t have been more simpático, and at first he seemed to take pains not to stare at her glorious figure, though he couldn’t help but smile at the way her youthful beauty certainly cheered things up. Okay, he was missing half his teeth, looked like he swallowed shadows when he opened his mouth, and had a bulbous, knobbed face, the sort of ugly man, somewhere in his forties or fifties-she couldn’t tell-who could never have been good looking, even as a boy. Once he got around to tipping up his brim, however, she could see that his eyes were spilling over with kindness, and despite his filthy fingernails she liked him for the thin crucifix he wore around his neck-a sure sign, in her opinion, that he had to be a good fellow-un hombre decente.

Heading northeast along dirt roads, the Cuban countryside with its stretches of farms and pastures, dense forests and flatlands gradually rising, they brought up clouds of red dust: along some tracks it was so hard to breathe that María had to cover her face with a kerchief. Still, to be racing along at such bewildering speeds, of some twenty or thirty miles an hour, overwhelmed her. She’d never even ridden in a truck before, let alone anything faster than a horse and carriage, and the thrill of traveling so quickly for the first time in her life seemed worth the queasiness in her stomach, it was so exciting and frightening at the same time. Naturally, they got to talking.

“So, why you wanna go to Havana?” the fellow-his name was Sixto-asked her. “You got some problems at home?”

“No.” She shook her head.

“What are you gonna do there, anyway? You know anyone?”

“I might have some cousins there, from my mamá’s side of the family”-she made a sign of the cross in her late mother’s memory. “But I don’t know. I think they live in a place called Los Humos. Have you heard of it?”

“Los Humos?” He considered the matter. “Nope, but then there are so many hole-in-the-wall neighborhoods in that city. I’m sure there’ll be somebody to show you how to find it.” Then, picking at a tooth with his pinkie: “You have any work? A job?”

“No, señor-not yet.”

“What are you going to do, then?”

She shrugged.

“I know how to sew,” she told him. “And how to roll tobacco-my papito taught me.”

He nodded, scratched his chin. She was looking at herself in the rearview mirror, off which dangled a rosary. As she did, he couldn’t resist asking her, “Well, how old are you anyway, mi vida?”

“Seventeen.”

“Seventeen! And you have nobody there?” He shook his head. “You better be careful. That’s a rough place, if you don’t know anyone.”

That worried her; travelers coming through her valle sometimes called it a city of liars and criminals, of people who take advantage. Still, she preferred to think of what her papito once told her about Havana, where he’d lived for a time back in the 1920s when he was a traveling musician. Claimed it was as beautiful as any town he’d ever seen, with lovely parks and ornate stone buildings that would make her eyes pop out of her head. He would have stayed there if anybody had cared about the kind of country music his trio played-performing in those sidewalk cafés and for the tourists in the hotels was hard enough, but once that terrible thing happened-not just when sugar prices collapsed, but when the depression came along and not even the American tourists showed up as much as they used to-there had been no point to his staying there. And so it was back to the guajiro’s life for him.

That epoch of unfulfilled ambitions had made her papito sad and sometimes a little careless in his treatment of his family, even his lovely daughter, María, on whom, as the years had passed, he sometimes took out the shortcomings of his youth. That’s why, whenever that driver Sixto abruptly reached over to crank the hand clutch forward, or swatted at a pesty fly buzzing the air, she’d flinch, as if she half expected him to slap her for no reason. He hardly noticed, however, no more than her papito did in the days of her own melancholy.

“But I heard it’s a nice city,” she told Sixto.

“Coño, sí, if you have a good place to live and a good job, but-” And he waved the thought off. “Ah, I’m sure you’ll be all right. In fact,” he went on, smiling, “I can help you maybe, huh?”

He scratched his chin, smiled again.

“How so?”

“I’m taking these pigs over to this slaughterhouse, it’s run by a family called the Gallegos, and I’m friendly enough with the son that he might agree to meet you…”

And so it went: once Sixto had dropped off the pigs, he could bring her into their office and then who knew what might happen. She had told him, after all, that she’d grown up in the countryside, and what girl from the countryside didn’t know about skinning animals, and all the rest? But when María made a face, not managing as much as a smile the way she had over just about everything else he said, he suggested that maybe she’d find a job in the front office doing whatever people in those offices do.

“Do you know how to read and write?”

The question embarrassed her.

“Only a few words,” she finally told him. “I can write my name, though.”

Seeing that he had made her uncomfortable, he rapped her on the knee and said, “Well, don’t feel bad, I can barely read and write myself. But whatever you do, don’t worry-your new friend Sixto will help you out, I promise you that!”

She never became nervous riding with him, even when they had passed those stretches of the road where the workers stopped their labors in the fields to wave their hats at them, after which they didn’t see a soul for miles, just acres of tobacco or sugarcane going on forever into the distance. It would have been so easy for him to pull over and take advantage of her; fortunately this Sixto wasn’t that sort, even if María had spotted him glancing at her figure when he thought she wasn’t looking. Bueno, what was she to do if even the plainest and most tattered of dresses still showed her off?

Thank goodness that Sixto remained a considerate fellow. A few times he pulled over to a roadside stand so that she could have a tacita of coffee and a sweet honey-drenched bun, which he paid for, and when she used the outhouse, he made a point of getting lost. Once when they were finally on the Central Highway, which stretched from one end of the island to the other, he just had to stop at one of the Standard Oil gas stations along the way, to buy some cigarettes for himself and to let that lovely guajira see one of their sparkling clean modern toilets. He even put a nickel into a vending machine to buy her a bottle of Canada Dry ginger ale, and when she belched delicately from all the burbujas-the bubbles-Sixto couldn’t help but slap his legs as if it was the funniest thing he had ever seen.