I leaped up from the sofa and announced I felt a bout of diarrhea coming on, which was really the only ailment my father ever took seriously.

"What did she eat?" he asked my mother.

"Cat shit," I said, running out of the room. "The kids at school made me eat cat shit today, because I'm wearing jeans from Sears."

My father believed at the time that reading was the only way for me to succeed in life. "You must not let your mind get weak." He never mentioned anything about not letting your bladder get weak, which turned out to be fortuitous for him and the hundreds of pairs of pants he's ruined since.

My mother came into my room later to ask how much the dolls were, and when I told her, she told me that my father would not be happy. By this time in my life, I'd had enough of their shenanigans and bargain hunting, and I definitely felt like I had plenty of stored resentment to make a case for myself. I walked into the living room, where my father had parked himself with a corned beef on rye, and stated my case.

"Here's the deal, guys. I can't go on like this. We can't go on like this. You two are a joke. I am nine years old, trying to make the best out of a situation that is unlike any of my peers'. I have five older brothers and sisters who seem to have fared better than me, mostly because you birthed them when the two of you had a clue as to how to raise a child. I am competing with people in this neighborhood who have access to swing sets, and in-ground pools I can only dream of, and cars that work the first time you try to start them. This isn't a good foundation for the rest of my life, because I will only end up never feeling like I'm enough or of any worth. I will depend on my looks, which will turn me into a shallow, eating-disorder whore who will end up selling her body just so she can buy herself an eternity ring. Reading the Boston Globe is not helping my cause. I can read the Boston Globe when I'm twenty. Right now I need to read Sweet Valley High and watch Family Ties and have sleepovers where we get 'the feeling.' I don't even know what you guys do for a living, which brings me to my next topic: Does either one of you have a job?"

"What's 'the feeling'?" my father asked.

"Don't worry about it," my mother interjected to save me. "It's a game they play with peanut butter."

"That's not the point, Dad. I need a Cabbage Patch doll. They're $49.99, and I need one. Do you copy?"

"Yes," he said. "I'll go first thing in the morning. You've made your case. Now, take all the papers into your room, and in exchange for one of these lettuce dolls I'd like you to review what you think of Reagan's trickle-down theory."

"I can tell you my answer to that before reading anything. If it means that people like us are eventually going to get free Cabbage Patch Kids from wealthier Jews in the neighborhood, I'm telling you right now I'm not willing to wait for that leak. I think we already have enough leaks in this house."

"Would you stop it with the complaining all the time? I told you if you see anything leaking, grab some duct tape and pitch in. Weren't you just talking about an arts-and-crafts class?" he reminded me.

"Fine, Melvin," I told him, grabbing the paper out of his hand. "But it has to be the one with brown hair, green eyes, no freckles, and one dimple. One dimple! I'm going to write it down for you. No redheads!"

"What if that's the only kind left, Chelsea? These dolls sound as if they're selling like hotcakes. We can always get a redhead and Mom can color her hair."

"Their hair is made of yarn, Dad. Okay, this isn't one of your Buick LeSabres that you can just spray-paint another color in the hopes of raising the price an extra hundred and fifty dollars and turning it into a 'classic.' Please get real."

"All right, enough already, we got it. No redheads."

Before I retreated to one of the kitchen drawers to retrieve a stained piece of paper that contained some forgotten grocery list that I had probably authored and wrote down the exact description of the doll being demanded, I told them, "And thank you for acknowledging your misstep in having me."

"Jesus Christ, Sylvia, you'd think she was raising us."

"Yeah, no fucking kidding," I mumbled on my way to the kitchen.

The next day at school was torture mixed with excitement. There was a part of me that was hopeful that my father would in fact hold true to his promise. Like a girl in an abusive relationship who hopes that her boyfriend will suddenly see reason and cease and desist with his attacks, I was cautiously optimistic. It was brutal watching everyone at school carrying their Cabbage Patches around, comparing eye color and dimples, who had bangs, who didn't, the birth certificates with their birth weight and full first, middle, and last names.

Instead of masturbating on the swing set that day, I took my forty minutes of recess to kneel in the woods and pray that my cheap Jewish father would somehow muster the courage to spend fifty dollars on a doll that would be able to provide no income for the family.

When I got home, my father was at the "auction." That was a used-car sort of swap meet for people who made no income from buying and selling used cars. The auction was every Tuesday at a place called Skyline. A more appropriate name would have been Loser Alley. This was the only real work commitment my father had all week long, if you could even call it work. The only other times he left the house were to show a car he had advertised in the newspaper or to go to the grocery store for his pastrami and corned beef stock-up.

Being at the auction meant my father wouldn't be home until seven. My mother kept assuring me he would have a Cabbage Patch with him when he returned. I sat in the front living room staring out the bay window at our circular driveway of cars that belonged in an episode of Dukes of Hazzard.

Finally I decided to start working on my Reagan essay, which was really quite challenging, since I had a hard time taking him seriously after my brothers and sisters revealed to me that he'd previously worked as an actor. What a joke. My father fancied himself a Republican, which was another joke. I told my father he didn't make enough money to be a Republican and decided that would be the focus of my essay. "Misguided Politics" is what I would call it. I started off by informing the reader, my father, that in order to consider yourself a member of any political party you first needed to register to vote.

From my bedroom I saw lights creep up the corner of our street, and I almost climaxed. I was so nervous I even picked up Poopsie Woopsie and started violently petting her.

Sure enough, in my father walked carrying the big cardboard box the dolls came in, with the plastic covering on the front. I nearly shit my pants.

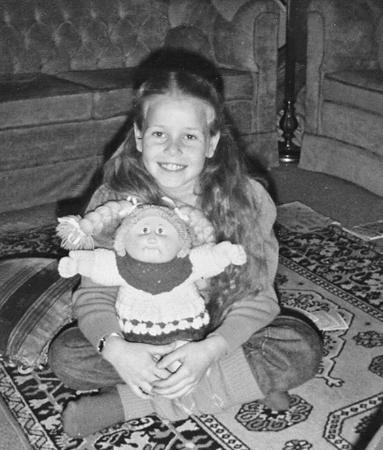

"AAAAAAhhhhhh!" I screamed. "Let me see!!!!! Let me see!" I dropped Poopsie Woopsie on my way down the steps to our front door and ran over to grab the box out of his hands. It was a real live Cabbage Patch Kid! Another second went by before I realized there was no brown hair. There was no hair at all. His name was Stanley. He was a preemie. And he was black.

I finally acquired the Cabbage Patch I had yearned for, Gretchen, when I stole it from my next-door neighbor Jason Rothstein, who had no business being around young girls in the first place.