27

FortBelvoir. Virginia, 1951

The chameleon also took an interest in UFOs; unlike the changeling, it moved in on the source of information.

It had spent thousands of years in armies, and in fact had been a Nazi in World War II. The Korean War was kind of unappealing, but the chameleon knew enough about military red tape that it was only a matter of patience to make itself an E4 clerk on the Pentagon staff, Airman (a title only a month old) Fourth Class Patrick Lucas. Once there, it listened to scuttlebutt and managed to move itself into Project Blue Book.

Once there, it gave itself a promotion in an irregular way, which it had done before: when a new bachelor officer was assigned to the project, the chameleon studied his personnel file, befriended him the first day, got him alone in his apartment, and killed him.

In the bathtub it performed a rough-and-ready autopsy, thorough enough to ensure that the officer was indeed human—because something like the chameleon, if such existed, might also be drawn to Blue Book.

It wrote a suicide note for Airman Lucas, and at two in the morning traded uniforms and dogtags with the officer. Drained of blood, the officer looked like a pale, passed-out drunk. The chameleon carried his body quickly to its car, and drove to the end of a dirt road outside of Vienna, Virginia. It saturated the body and the front seat with gasoline, tossed in a match, and changed its appearance, almost instantly, to match the officer’s. Then it ran through the woods back to civilization.

The short newspaper article only said that the body had been burned beyond recognition, but the car was registered to a Pentagon clerk. Investigators that morning found the suicide note, and the case was closed. Coworkers shook their heads; he always had been a loner.

The new lieutenant seemed to be a loner, too, and once the theory that he was a plant from the CIA was whispered around, people pretty much did leave him alone.

The chameleon-lieutenant’s function for several months was to winnow through UFO reports, to find the 10 percent or so that warranted some follow-up. It ordered calendars back to 1948, and with the aid of an ephemeris, marked off the evenings and mornings when the planet Venus was particularly bright. That saved a lot of time.

It knew about Projects Sign and Grudge, and was not surprised to get the feeling that Blue Book was less interested in scientific evaluation of UFO reports than in public relations, mostly debunking. Some people saw evidence of a conspiracy there, but the chameleon just saw the conservative military mind at work. Project Blue Book was basically one officer and a few low-ranking clerks, with a couple of dozen other people, military and civilian, poking their noses in every now and then.

It seemed to spend as much time dealing with the press and politicians as with UFOs. Whenever there was a slow news day, reporters would show up or phone, in search of copy. Politicians would demand to know why nothing had been done about some sightings in their districts.

With a typically military instinct for putting the right man in the right job, they put the chameleon in charge of the phone. Of course, it had had thousands of years’ experience in dealing with people. But tact had never been its usual weapon of choice.

The chameleon observed its fellow investigators as keenly as it did the pilots and police and farmers who had reported the phenomena, reasoning that if there were something else like it in the world, it might gravitate to Fort Belvoir. But its counterpart was on the other coast, involved in the same pursuit in its own way, having given up on flying saucers.

After another year, the chameleon did, too. One day, instead of reporting for duty, it drove on into Washington and bought a wardrobe of work clothes from used-clothing stores, and by the time its superiors realized one of their investigators had gone AWOL, it was working on a dairy farm in western Maryland.

28

Apia, Samoa, 2021

The idea of signaling alien intelligence with a message that didn’t depend on language went back to 1820: the mathematical genius Carl Friedrich Gauss suggested clearing an immense section of Siberian forest, and then planting wheat in three squares that would diagram the Pythagorean theorem. An observer on Mars would be able to see it with a small telescope.

There were other schemes in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, involving mirrors reflecting sunlight, huge fires demonstrating geometrical shapes, or cities blinking their lights on and off.

Around 1960, Mars no longer a compelling target, Frank Drake and others suggested an elaboration of this “Morse code” approach that would be visible from interstellar distances, using radio telescopes as transmitters rather than antennas, sending out a tight beam of digital information. The reasonable assumption was that any civilization advanced enough to receive the message would be able to understand binary arithmetic. So they sent, in essence, a series of dots and dashes that said “1 + 1=2,” and went on from there.

The idea was to establish a matrix, a rectangle of boxes that would make an understandable picture if you made some of the boxes (corresponding to “1”) black and left the others (corresponding to “0”) white—like a crossword puzzle before it’s filled out.

For it to make sense, you had to know the dimensions of the rectangle. The easiest way to do it would be to broadcast the information one line at a time, with pauses between the lines. Then a longer pause, and repeat the same thing over, for verification.

That does take a long time. Drake suggested that a single long string of ones and zeros would suffice, if there were some way to tell how many of them made up each line.

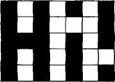

Prime numbers were the answer. Any pair of prime numbers, multiplied together, produces a number you can’t arrive at with any other pair. The number thirty-five can only come from seven times five, so a sufficiently clever alien could look at this string of ones and zeros:

and come up with this rectangle:

Of course a five-by-seven rectangle is just as likely, but gives this:

—which we would hope is not insulting in the alien’s language.

With a large enough number of spaces, the difference between order and chaos is obvious. Drake’s example was 551 characters, which made a map twenty-nine by nineteen spaces. Of course it didn’t spell out an English word; in fact, it was meant to be an incoming signal: it showed a crude drawing of an alien creature and a diagram of its solar system, along with other shapes that indicated it was carbon-based life, that it was thirty-one wavelengths tall, and that there were seven billion individuals on its planet—and three thousand colonists on the next planet in, and eleven explorers on the next one.

The message Jan would send the artifact used the same technique, though it could be much more elaborate, since the receiver was inches away rather than light-years. Starting with the same arithmetic and mathematics, it went beyond a stick-figure-plus-DNA diagram to present digital representations of Einsteinian relativity, photographs of several different people, a Bach fugue, one of Hokusai’s views of Fujiyama, and Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring in black and white.